Invest in public health now, or store up problems for the future

12 June 2019

The 2019 spending review is highly likely to be delayed, meaning key policy decisions may be put off for another year. This could be damaging for public health outcomes. Although the government has committed to increasing spending on NHS England, the future of the public health grant remains uncertain. Clear and immediate action is needed to ensure the government provides local authorities with the resources to deliver vital local services that play a key role in improving and maintaining the population’s health.

Why does the public health grant matter?

The public health grant allows local authorities to provide services that are vital to maintaining and improving people’s health. It was recently confirmed that responsibility for the grant will remain in the hands of local authorities. However, after 5 years of cuts and consultations, its future size and shape remain unclear. Without a long-term plan for public health funding, it’s difficult for local areas to make the strategic decisions required to best support our health.

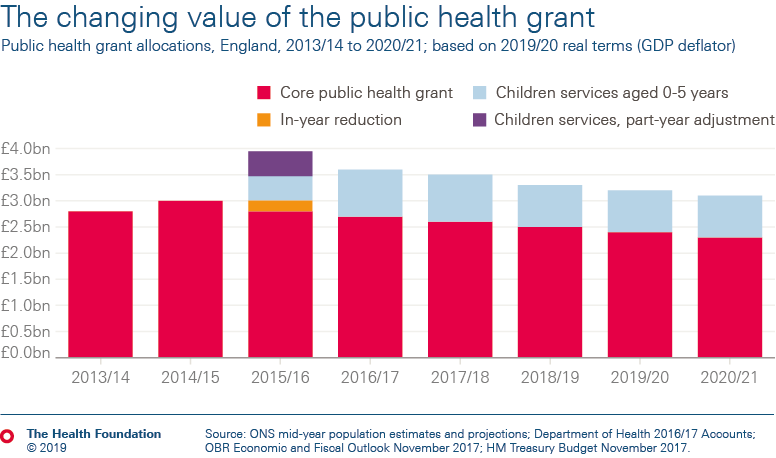

The public health grant, currently £3.1bn a year, was first introduced in 2013/14. At this point, responsibility for preventative services – such as sexual health clinics, stop-smoking support, and drug and alcohol abuse services – moved from the NHS to local government. Responsibility for services for children aged 0-5 years was also moved to local government in the middle of 2015/16, with the annual equivalent of an additional £0.9bn a year of funding. But the total value of the public health grant has declined (in real terms) since 2015/16.

How much has the public health grant been cut by?

The chart below shows that public health grant allocations for 2019/20 are £850m lower than when the grant was implemented in 2015/16. Without a spending review this year, if provisional allocations are put into place, there will be a further £50m reduction next year. Per capita, that equates to a real-terms funding cut of 25% between 2015/16 and 2020/21.

To provide some sense of the scale of these reductions, between 2013/14 and 2020/21 NHS England spending is set to have increased by over 20% in real terms. That is an increase of over £20bn in annual spend for NHS England, compared with the public health grant, which is £3.1bn in total each year.

Yet cutting public health funding risks storing up more acute health problems in the future, the burden of which are likely to fall on the NHS – not to mention potential wider pressures on other services such as the police and social security. We only need to look at recent IFS research into the impact on health of Sure Start centres to understand the risks to health of cutting spend in such areas.

Our health is a product of the conditions we live in, the social determinants of health, which themselves are dependent on a wide range of factors – including government activity. Public health provision plays a key role in maintaining and improving our health. That’s why the Health Foundation and The King’s Fund are calling for government to reverse the real-terms per capita cuts to the public health grant. That would be the equivalent of a £1bn boost to funding in 2020/21 (the notes below show how we’ve calculated this).

Public health grant must rise in line with NHS England spending

Once restored, the Health Foundation’s view is that the grant should then be raised in line with growth in NHS England spending, in order to maintain the proportion of total health spending being devoted to public health, and to prevent spending being further skewed away from prevention and towards treatment. This would need the public health grant to reach a total of £4.6bn in 2023/24, with this additional funding phased in over the next 4 years. In real terms, that would be a £1.5bn increase (relative to plans for 2020/21 as they stand), which would have a positive effect beyond reversing previous cuts. The additional money should be targeted where there is the most need: in deprived areas that are experiencing the greatest health problems.

In our Taking our health for granted briefing last year, we estimated it would take more than £3bn of additional investment (on top of the current grant) for the public health grant to be fairly distributed. This investment would enable the grant to take local variations into account without reducing existing allocations in any area, which was the original aim of the public health grant allocation formula. But moves to create this equitable distribution stalled as the grant was reduced.

The minimum £1.5bn increase by 2023/24 set out above would reduce that funding gap by less than half. Closing the gap entirely should be the government’s ambition.

Planning for the future of public health funding

The other uncertainty related to the grant is whether it will remain a grant at all. The planned move towards 100% business rate retention – also likely to be put off for another year – would see public health funded through this locally raised revenue pot. But the precise amount and distribution mechanisms are still being considered. Reinstating the value of the public health grant, consideration of exactly where funding for the grant should come from and ensuring the fair allocation of resources should form a key part of such a plan, if it goes ahead.

From life expectancy to obesity and mental health, many indicators of health are either showing little sign of improvement or getting worse. Public health services play a key role in improving and maintaining our health, and in turn can help reduce long-term demands on the NHS by preventing ill health in the first place. If the government is serious about the nation’s health now and in the future, decisions about public health spending can be delayed no longer. Instead of rolling budgets over to next year, the government must start reinvesting in the public health grant this autumn.

David Finch (@davidfinchRF) is a Senior Fellow at the Health Foundation.

Notes

- Public health grant amounts are published allocations. We assume the share of the overall grant allocated to children's services remains constant relative to the size of the original grant.

- The £200m in-year reduction is applied to the original grant elements in 2015/16. The actual grant payment for children in 2015/16 amounted to part of the full year allocation, as services were transferred halfway through the financial year.

- The £1bn boost consists of the £850m cut for 2019/20 (calculated purely accounting for changes in costs) plus the additional £50m cut expected in 2020/21. Then an extra £100m factored in to account for population growth, taking the amount required up to a total of £1bn in 2020/21 to restore real-terms per capita funding.

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more