Key points

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) is putting unprecedented pressure on the UK health and social care workforce, and has exacerbated existing staff shortages. Nursing is one critical area. The NHS in England alone went into the pandemic with vacancies in about one in ten registered nursing posts – about 40,000 full-time equivalents.

- Prior to the pandemic taking hold, the NHS had become increasingly reliant on international recruitment to plug domestic nursing vacancies. Foreign-trained nurses accounted for 15% of the UK total of registered nurses in 2019, markedly higher than most other OECD countries.

- Data from the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) show that nurses trained outside the EEA have accounted for an increasing number of new international registrations since the Brexit vote. There has also been a corresponding reduction in the number of nurses trained in the countries of the EU/EEA. As a proportion of the overall number of new NMC registrations, international (non-UK) inflows have grown since 2015/16, accounting for over a third (34%) of new registrations in 2019/20.

- With COVID-19 disrupting international travel and putting pressure on source countries, the UK witnessed a sharp (97%) reduction in new registrations from nurses trained outside the EEA in April 2020 (from 1,348 in March to only 35 in April). This decline may have been negated in the short term by the NMC having encouraged international nurses already in the UK to sign up for its ‘temporary register’, and there is likely to be an increased inflow of nurses from abroad as and when there is an easing of travel restrictions. Nonetheless, there are longer term questions posed by the negative economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and related NHS funding constraints.

The impact of COVID-19 has highlighted the central importance of registered nurses to health and social care services in the UK. It has also further exposed the current shortfall in NHS nurses. The NHS in England alone went into the pandemic with vacancies in about one in ten registered nurse posts – about 40,000 full-time equivalent staff. In addition, there was a similar vacancy rate for nurses in adult social care in England.

The NHS Long term plan, and the Interim NHS people plan, both recognised the need to fill these vacant NHS posts. The pre-COVID-19 strategy was put in place essentially to ‘buy time’ – for growth in levels of domestic training and improvements in retention – by ramping up international recruitment. At an estimated cost of £12,000 per non-EEA nurse recruit, it can be relatively quicker and cheaper than investment in domestic training.

However, the global disruption to recruitment and travel caused by COVID-19 has now called into question the likely effectiveness of the international nurse supply route. In June, the Chief Executive of the NMC noted that the NHS must think ‘long and carefully’ about its reliance on international recruitment, as it will be ‘difficult’ following the COVID-19 pandemic. However, earlier this week, the Chief Nursing Officer in England reported to the House of Commons’ public accounts committee that several thousand international nurses were ready and waiting to travel to work in England when COVID-19 related travel restrictions were eased.

Does the impact of COVID-19 mean the UK needs to ‘think local’ for its future nurse supply, or can it switch back to going global? In this analysis we first look at how the UK compares to other countries in terms of its level of reliance on international nurses, and then assess long-term trends in international supply, before considering the implications of COVID-19.

The UK’s reliance on international nurses

We have been tracking the UK’s long-term reliance on international nurses and have highlighted the variable but often high levels of international nurses coming to the UK to register and become eligible for practice. In recent years this reliance has been brought into sharp focus with the Brexit vote and, more recently, the impact of COVID-19 as a second external shock.

For any country, the extent of its vulnerability to disruption in the international supply of nurses will be correlated to the level of reliance on international nurses. And the UK is one of the most dependent countries in this regard, with about 15% of registered nurses being foreign trained – more than double the average for high-income OECD countries.

There are almost 720,000 nurses and midwives on the NMC register, the ‘pool’ from which all employers must recruit. More than 100,000 of those nurses were trained in another country – approximately one in seven of the total stock of registered nurses. There are around 30,000 registrants from EEA countries, and just over 84,000 trained in other non-EEA countries.

Beneath this national headline rate of around 15% of nurses being foreign trained, there are varying levels of reliance on nurses (and therefore vulnerability) in different parts of England. NHS data shows that the proportion of non-EEA nurses varies from 30% to 36% in London regions to between 5% and 8% in the north-east, north-west, and Yorkshire and Humber regions.

Trends in international supply

The year-on-year pattern of international inflows of nurses can be assessed using data from the NMC (previously the UKCC). The chart below shows the annual number of international nurse registrants first registering in the UK, from EEA and non-EEA countries since 1990. The pattern is clear. There was a rapid increase in the non-EEA international inflows in the period up to 2001/02, mainly driven by the active recruitment of nurses from the Philippines and India, at a time of NHS funded staff expansion. This was followed by a decline in non-EEA inflows in the period up to 2009/10, driven by stricter immigration rules and a more expensive application regime for international nurses.

There was then a second phase of increased international nurse inflows (2010–2016) as UK employers struggled to address nursing shortages, mainly switching to recruitment from EEA countries such as Romania, Spain, Portugal and Italy. Finally, in the most recent period since 2016, which saw the Brexit vote and new English language test requirements for nurses, there has been a rapid decline in inflows from the EEA but a rapid increase in non-EEA international recruitment. Again, mainly resulting from a switch back to India and the Philippines. The inflow of registrants from non-EEA countries doubled in 2019/20 relative to the previous year (from around 6,150 to over 12,000).

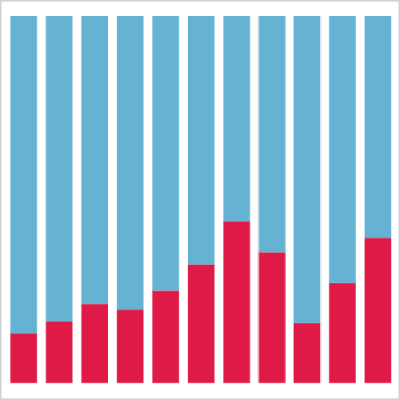

We have seen a rapid increase in nurse registrants from non-EEA countries to the UK. In early 2020, just before the pandemic hit, the annual inflows were nearing historically high levels last seen 20 years ago. Comparing the numbers of new annual registrants from the UK to those from other countries gives an insight into the relative importance of each source. In every year since 1990, at least one in every ten new entrants to the NMC register has come from other countries (see the chart below). In most years this percentage of inflows from outside the UK has been much higher, peaking at over 50% of the total in 2001/02. Most recently, international inflows have again risen in prominence, from 23% of new registrants in 2018/19 to 34% in 2019/20.

Impact of COVID-19

Against this backdrop of an increase in the proportion of international hires, COVID-19 has come as a major external shock. Monthly data from the NMC suggest that the number of nurses trained outside the EEA joining the NMC’s permanent register plummeted from 1,348 in March to only 35 in April (see the chart below), with COVID-19 imposing a stranglehold on international travel and leading to some key source countries bringing in exit constraints for health workers.

This poses a major short-term challenge for the UK given its increasing reliance on non-EEA nurse hires, even accounting for any short-term fall in the emigration of UK-based nurses given the pandemic. To an extent, the NMC addressed this bottleneck by permitting a large number of non-EEA nurses, who were already in the UK, to join its ‘temporary register’. This was introduced in March to bolster the UK’s pandemic response, without completing otherwise obligatory regulatory and testing requirements. That led to what is likely a ‘one off’ additional 2,006 non-EEA nurses joining the temporary register in April. It is not yet clear what the status of nurses on the temporary register will be in the longer term.

Summary

Nursing shortages have been driving an upward trend in the number of UK employers wishing to use active international recruitment. But in recent years this has been impacted by two external shocks – the impact of the Brexit vote in mid-2016, and the impact of COVID-19 in 2020.

NHS recruiters adapted to the first by switching to non-EEA recruitment. The impact of COVID-19 is likely to lead to a redoubling of efforts to increase international recruitment, in part to compensate for likely reductions in short-term domestic supply. In particular, retired and non-practising nurses who came back into the workforce to fight the pandemic’s front line will have to step back, and other working nurses are arguably more likely to take time away from work because of burnout. COVID-19 has also caused short-term disruption to international recruitment and remains a ‘known unknown’ in terms of its longer term impact on international nurse supply.

However, as and when travel disruptions are eased, there is a pent up supply of international nurses from countries such as the Philippines. Their decisions on where they go will depend on which destination countries offer them the most attractive package of earnings, career opportunities and living and working conditions. As we have highlighted, in the past the UK has not encountered great difficulty in recruiting large numbers of nurses from other English-speaking countries. In the near future, the fact that nurses are on the UK’s shortage occupation list, coupled with the government’s recent proposals for a post-Brexit Health and Care Visa, and the recent exemption of nurses from the Immigration Health Surcharge, should further facilitate the ‘fast track’ recruitment of nurses trained abroad. But in a post-COVID-19 world, the UK will have to compete with other OECD countries looking to reduce their own nurse staffing shortfalls, such as Germany.

Two longer term issues must be kept in mind. First, there is a risk that any further ramping up of active international recruitment by the UK could damage fragile health systems in source countries. These countries are already having to deal with a major pandemic with inadequate nurse numbers. The UK has endorsed the WHO Global code of practice on the international recruitment of health personnel. This sets out a framework for a managed and ethical approach to international recruitment, and the UK should continue to comply with the code.

Second, the underlying challenge faced by the UK in recruiting nurses from other countries will not be the short-term supply disruption arising from this phase of COVID-19, but rather the longer term negative economic impacts of the pandemic and related NHS funding pressures, with clear implications for workforce policy and planning in both health and social care. This may mean that the real question is not whether the UK can recruit more international nurses, but whether the NHS has the funding to employ them.

We are grateful to the NMC for providing data on the monthly number of new nurse registrations for September 2019–April 2020, which informed this analysis.

James Buchan is Senior Visiting Fellow in the Economic teams at the Health Foundation.

Nihar Shembavnekar is an Economist at the Health Foundation.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more