Understanding activity in general practice: what can the data tell us?

24 February 2022

Key points

- General practice is under pressure, managing high volumes of routine work alongside responding to COVID-19. Including COVID-19 vaccinations, appointments are at high levels compared to previous years. Even without including these, appointments in November and December 2021 exceeded the same months in 2019.

- The number of fully qualified full-time equivalent GPs has declined since 2015. While the number of GP trainees and non-GP patient care staff in general practice is increasing, it’s not clear this is enough to allow general practice to deliver either what’s being asked, or to hit key workforce targets.

- Limitations on the data available mean we don’t know enough about activity and workload in general practice. Data about appointments and referrals provide some insight but have constraints. There are other areas of general practice activity, such as administrative work or clinical supervision, where available data tell us very little.

- The government and NHS England have set out plans to improve access to general practice and increase the proportion of face-to-face appointments. Improving general practice activity data would help frame expectations about what can be achieved, and track progress.

Introduction

COVID-19 has meant activity in general practice has changed dramatically over the last 2 years. Practices have moved rapidly towards remote triage and care delivery to reduce risk of infection. Many have also delivered a large proportion of the COVID-19 vaccination programme as part of Primary Care Networks (PCNs), alongside their usual patient care.

Understanding the total workload of general practice is vital for planning, research and supporting practices under pressure. However, the data we have on activity in general practice are limited, especially compared with hospital data. This has made it challenging to accurately track the ongoing impact of COVID-19 on general practice.

Activity data have also been open to misinterpretation and oversimplification during the pandemic. For example, appointments data show a significant drop in consultations in April and May 2020 (when the UK was under severe social restrictions) but do not capture the significant workload associated with changing models of service delivery to meet new infection control guidelines.

With publication of the government’s general practice access plan and requirements to increase the proportion of appointments done face-to-face, activity in general practice is under increasing scrutiny. Understanding the data provides important context for expectations around access, and what can be achieved, given current workforce constraints.

This short analysis uses data from different sources, some publicly available and some not, to explore recent trends in general practice activity in England. We also present data on the general practice workforce, to help contextualise activity levels. We highlight what the data can tell us – and importantly, what it can’t.

GP appointments data

Since 2018, the NHS Digital Appointments in General Practice dataset has been an important source of activity data for general practice in England. It is designed to provide a minimum level of information on appointments. NHS Digital classify it as ‘experimental’, to indicate quality challenges (discussed in more detail below). But the introduction of this dataset represents a major step forward in publicly available activity data for general practice.

Excluding COVID-19 vaccinations, latest data show there were 25.7 million general practice appointments in January 2022. In addition, in January 2022, general practice delivered 1.26 million COVID-19 vaccination appointments.

November 2021 saw the highest number of standard GP appointments on record so far at 30.5 million. Including COVID-19 vaccinations, November 2021 also saw the highest total number of appointments to date at 34.8 million.

Modes of appointment have changed because of the pandemic. In February 2020, around 80% of general practice appointments were provided face-to-face. Following government advice, the proportion of face-to-face appointments dropped to around 47% in April 2020. The proportion of appointments done by telephone rose rapidly at this time while the proportion done via video or online saw only negligible change.

From February 2020 to January 2021, the proportion of appointments done face-to-face fell during periods of lockdown and high infection rates, and rose afterwards. From January 2021 to October 2021, there was a more consistent rise in the proportion of face-to-face appointments. This is likely due in part to NHS and government requirements to increase face-to-face care. Data from the final 2 months of 2021 along with January 2022 show the proportion of face-to-face appointments declining slightly once again.

General practice is increasingly moving to a multidisciplinary model of working. Many different staff groups are now providing appointments to patients, including practice nurses, social prescribing link workers, clinical pharmacists and many others. While the exact ratio changes over time, these other practice staff collectively provide around the same number of appointments as GPs.

What the GP appointments data can and can’t tell us

The NHS Digital Appointments in General Practice dataset is often treated as though it captures all the kinds of work taking place in general practice and that the data are complete. However, there are three important limits to bear in mind – scope, quality and detail.

Scope of the data

Patient appointments are just one part of the activity that goes on in general practice. A lot of other essential work is done by GPs and their teams to support patients and the practice itself. This work includes:

- clinical supervision of staff providing direct care to patients by GPs and other senior clinicians (to ensure quality and safety of care)

- admin and clerical work such as registering new patients, managing the practice business, providing fit notes and reporting against quality indicators

- reviewing repeat prescriptions to make sure they are correct and appropriate

- teaching, training and learning for all members of the practice

- liaising with other parts of the health and care system, including patient referrals, advocacy and communicating with hospital specialists about patient care

- management and organisation of their primary care network.

NHS Digital’s supporting information clearly states that this dataset captures very little, if any, of this activity.

Quality of the data

The appointments dataset is based on data collected from practice IT systems. These systems are used by GPs for managing their patient appointments and records. They are designed for practical use by GPs in managing their day-to-day work, so different practices fill in their records in different ways. This means the data they contain vary in completeness and quality.

Most of these systems also rely on GPs and other staff manually ‘coding’ and classifying the data they enter. This includes manually changing the appointment type in the IT system from the default settings every time (for example changing the appointment type from face-to-face to telephone). If this isn’t done consistently, the data collected become inaccurate.

There are also different suppliers of GP IT systems. Differences in the way these systems store and structure the data they hold adds further variability to the data that practices provide.

The dataset also struggles to capture appointments which tend to be recorded outside of core GP systems. For instance, NHS Digital suggests extended access appointments aren’t well captured in the data because of this.

The rapid rise in telephone appointments and the use of new digital tools may also mean that new ways of working aren’t reflected well in practice IT systems. For example, a GP might make calls to several patients in one ‘appointment’ slot logged within their system. Therefore, the number of actual patient contacts may be different from the total number of appointments in the dataset.

More information on these caveats around the appointments dataset can be found on the NHS Digital website.

Detail of the data

Because of the design of the dataset and the constraints on the data, the Appointments in General Practice dataset is not detailed enough to give us some important breakdowns.

As patient data aren’t provided to NHS Digital, the appointments dataset lacks information on patient demographics, or what each appointment is for. This means we can’t see, for example, the age breakdown for patients receiving face-to-face vs remote appointments.

Similarly, because of variability in the way practices use their appointments systems, the quality of information about which staff groups are providing appointments is poor. The dataset is unable to break down the number of appointments provided by different staff groups apart from providing GP and non-GP categories. This means we also can’t see the proportion of appointments delivered face-to-face broken down by these different staff groups.

CPRD activity data

Other data sources can give insight on general practice activity. One example is the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) datasets.

CPRD collects anonymised patient data from a network of GP practices across the UK. It covers around 2,000 practices and 16 million current patients. Data from this sample of practices have advantages over the NHS Digital Appointments in General Practice dataset.

CPRD data give greater detail about activity and a longer time series, including for appointments. This allows us to explore specific questions such as how the mode of delivery for appointments has varied for patients of different ages, or by staff group providing them.

The data presented cover England only.

The data show that patients aged 70 and older, and children younger than 11, saw a lower fall and greater recovery in the proportion of their appointments which were face-to-face from March 2020. This suggests GPs are making judgements about which groups need to be seen face-to-face to receive appropriate care and prioritising accordingly.

CPRD data also show that while the proportion of appointments conducted face-to-face has fallen below pre-pandemic levels for all staff groups, practice nurses have been providing significantly more of their appointments face-to-face than GPs.

It is likely that staff such as practice nurses and phlebotomists (staff who take blood samples from patients) have provided a sizeable proportion of the face-to-face appointments during pandemic, with the GP share falling. This is because key parts of their work, such as taking blood or providing childhood immunisations, can’t be done over the phone.

While CPRD data do have a number of benefits, there are drawbacks. The data aren’t publicly available. Data have to be purchased, requiring an application process including a statement on what they will be used for. Collection and processing by CPRD yields high-quality data suitable for academic research, but introduces significant time lags.

CPRD doesn’t aim to provide a complete ‘census’ picture of all general practices (in the way that the NHS Digital dataset does). The dataset also requires skilled analysts to clean and process the data and to construct samples that are representative of all general practice in England.

Further analysis of what the CPRD dataset can tell us about GP consultations during COVID-19 can be found as part of the Health Foundation’s contribution to the work of the ONS, DHSC and SAGE (paper published on 9 September 2021).

Referral activity

Alongside appointments, there are other indicators that can help paint a picture of activity in general practice. Referrals are a good example: where a GP or another member of the practice team arranges for a patient to receive assessment or treatment by another service, for example hospital-based specialists or community support.

Other parts of the health system make similar referrals to the same services. This sometimes means data are reported in an aggregate way that obscures the number of referrals from general practice. For example, national data on referrals for consultant-led routine care do not specify the proportion of these referrals coming from general practice.

Exceptions are urgent cancer referrals and referrals to first consultant-led outpatient appointments. These do have data specific to general practice and can show us another part of GP activity.

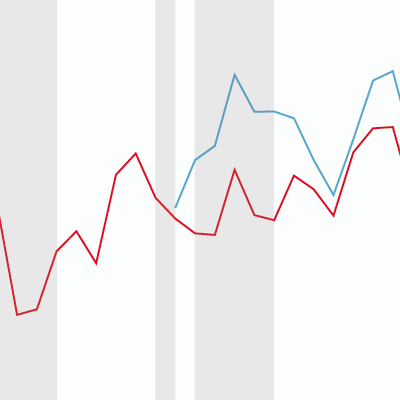

NHS data show GP referrals for ‘urgent’ 2-week wait cancer referrals dipped significantly between February and April 2020 and slightly in early 2021. Referrals appear to have recovered relatively quickly each time and are now back to pre-pandemic levels.

However, this picture is incomplete. There has not been a visible period of ‘catch-up’ activity following the early 2020 dip, and activity throughout most of the pandemic has also been lower than historic pre-pandemic growth trends might predict. This has led to estimates of ‘missing’ urgent cancer referrals during the pandemic.

Unlike urgent cancer referrals, referrals to first consultant-led outpatient appointment are still well below pre-pandemic levels.

Falling referrals from GPs are driven by a combination of factors, such as patients not coming forward for care or lack of capacity in secondary care to accept referrals because of COVID-19 pressures.

Other sources of activity data

While appointments and referrals data are the best overall indicators currently available for GP activity, there are others. These include routinely collected information such as general practice prescribing data, or other proxies such as self-reported GP workload.

Upcoming analysis from the Improvement Analytics Unit will draw on data from providers of digital tools to general practice to describe activity. These tools enable patients to book and receive appointments online as part of digital first primary care. The analysis provides insight into how patient demand, and modes of access and delivery of primary care, have varied before and during the pandemic. It also considers variation according to patient characteristics, preferences for different modes of delivery, and what patients are seeking appointments for.

Across all sources, there remain significant gaps in our understanding of general practice activity. We lack data about staff management, clinical supervision and administrative work, which aren’t usually captured in GP IT systems or in other existing data reports.

Workforce

The amount of activity general practice can deliver depends on the staff available.

Major efforts have been launched to recruit more GPs and retain existing ones. These have centred around key targets, including the 2015 Conservative manifesto pledge for 5,000 more GPs by 2020, and the current target – set out in the 2019 manifesto – for 6,000 more GPs by 2025.

In 2019, the government also committed to increasing the number of other staff providing patient care in general practice by 26,000 by 2024. This includes roles such as clinical pharmacists, social prescribing link workers and physiotherapists. These new staff are being recruited to Primary Care Networks and are being funded centrally through the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme (ARRS).

Understanding GP numbers

Different figures for GP numbers in England are often reported. These arise from different ways of classifying or counting GPs as well as from recent methodology changes, such as:

- Headcount vs full-time equivalent: Headcount is the number of individual GPs working within the NHS. Headcount doesn’t accurately reflect staffing levels, as some GPs work less than full-time, and others take on additional hours. Instead, a full-time equivalent (FTE) figure is often calculated. This converts the total number of hours worked by all GPs into an equivalent number of full-time GPs (defined as a GP working 37.5 hours per week) to standardise the data. Nationally, headcount is usually significantly higher than FTE.

- Qualified vs training: Doctors training to be GPs spend time working within general practice under the supervision of fully qualified GPs. These trainee GPs see patients and work within the practice but have limitations placed on them. Some counts of GP numbers report both trainee and fully qualified general practitioners together as ‘GPs’.

- Permanent vs locum: Fully qualified GPs can also be divided into two groups. Most are permanent staff, employed by a specific practice – either as a GP partner or a salaried GP. Some qualified GPs work as locums who move between practices, temporarily filling in for other GPs (for example to cover sickness or maternity leave). Counts of GP numbers sometimes exclude locums and report only ‘permanent’ or ‘regular’ GPs.

- NHS Digital methods: Starting with the release of the June 2021 data, NHS Digital changed their methodology for estimating missing workforce data for the minority of practices not reporting workforce information. Non-reporting was a more significant problem in the first year of the data collection in 2015.

The main result of this change was that the recorded number of GPs working in 2015 was significantly reduced as estimated totals for non-reporting practices were removed. As the 2015 figures are used as the baseline for many comparisons, this has a substantial impact.

As of the release of the December 2021 data, NHS Digital has revisited the methods and revised their estimates of the number of GPs working in general practice in 2015 upwards again. Different sources may cite different figures for historic trends because of these changes. Unless otherwise stated, we use the data from the February 2022 release.

Overall GP headcount (including trainee GPs) has risen by 4,362 since 2015. This equates to 1,799 in FTE. However, the number of fully qualified FTE GPs has fallen by 1,516 since 2015. This shows the government’s 2020 target of 5,000 additional GPs was not met. Based on current trends, the Health Secretary Sajid Javid has also now suggested the 6,000 target by 2025 is unlikely to be met either.

Data also show the inequitable distribution of GPs across England. Areas of high deprivation have fewer GPs per head of population than less socioeconomically deprived areas.

Other general practice staff

GPs are not the only staff working in general practice – nor are they the majority. Staff in other roles (eg practice nurses and first contact physiotherapists) offer appointments and patient care. Others, such as administrative staff or practice managers, are responsible for non-clinical tasks that keep practices running.

FTE numbers of nurses in general practice have increased overall compared with 2015 but have been declining from a peak in December 2019. Other roles providing patient care such as pharmacists, physiotherapists and social prescribing link workers have increased much more rapidly. This follows the introduction of the ARRS in 2019. However, at the current rate of growth, it is unclear if the 26,000 target for these additional roles will be met by 2024.

Conclusion

Activity in general practice can only be understood by combining a number of different sources. This piece focuses on what the data say about general practice activity at the national level in England. However, local level data are also important for understanding pressure points and highlighting inequities and unwarranted variation. Even then, the picture is still incomplete. Overall, there is a clear need for improved general practice activity data.

The number of staff available limits what activity can be delivered in general practice. GP appointment numbers are now higher than they were pre-pandemic, but the number of permanent fully qualified FTE GPs has fallen since 2015. Available data do not capture total workload in general practice, but surveys suggest that staff are exhausted, and many are considering leaving. National policy ambitions to improve access to general practice need to be based on a detailed understanding how activity is changing and a realistic assessment of the resources available to deliver expanded services.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more