Anchors in a storm

Lessons from anchor action during COVID-19

Anchors in a storm

20 February 2021

Key points

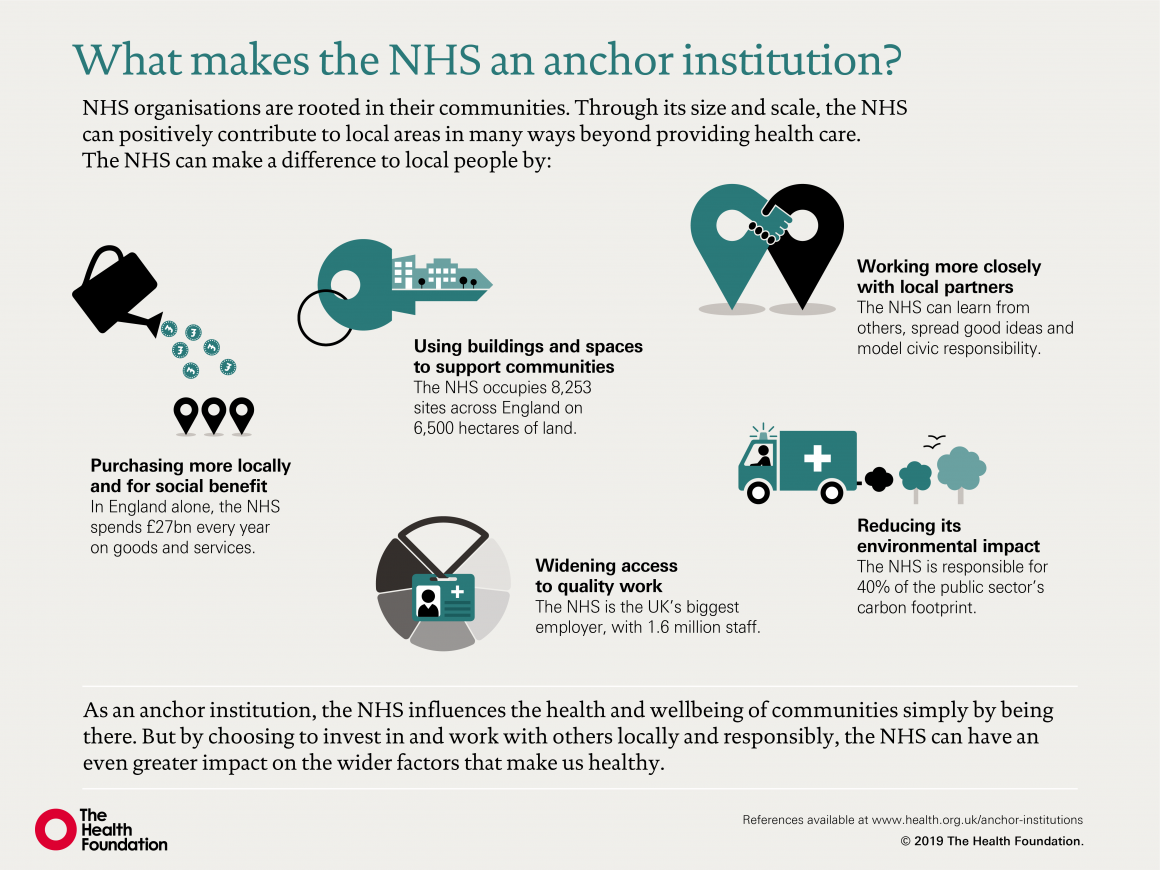

- ‘Anchor institutions’ are large public sector organisations rooted in and connected to their local communities. They can improve health through their influence on local social and economic conditions by adapting the way they employ people, purchase goods and services, use buildings and spaces, reduce environmental impact, and work in partnership.

- The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has galvanised many institutions, including the NHS, into more purposeful anchor action. The Health Foundation hosted and facilitated conversations about anchors and COVID-19 with anchor leaders and partners from eight local areas across the UK. The aim was to better understand the opportunities, challenges and priorities for anchor action within the health care system.

- Here we identify nine key lessons from these conversations to guide and inspire existing and emerging anchor leaders. The first two lessons – purposefully tackling inequalities and co-producing with communities – are guiding principles that should lie at the heart of all anchor action.

- We supplement these insights with case studies and practical examples of anchor action prior to and during the pandemic. Sharing learning and insights especially on measuring impact will be key to progressing this agenda.

- The leaders we spoke to were clear that the NHS has an opportunity and a responsibility to improve health, tackle inequities, and contribute to developing thriving local communities. COVID-19 may have enhanced the need for this work, and accelerated implementation in some areas, but anchor action will be important during COVID-19 recovery and beyond.

- The new Health Anchors Learning Network aims to support NHS anchors develop their capacity and capability to maximise their economic, social and environmental impact.

Anchors and COVID-19 conversations

Between August and November 2020, the Health Foundation hosted and facilitated eight virtual conversations about anchors and COVID-19. Our aim was to gain insight from local anchor leaders about the opportunities, challenges and priorities they faced for anchor action in light of COVID-19 and its impact on pre-existing anchor work.

To capture the diversity of anchor approaches, we held conversations in a range of geographical locations and across institutions at varying maturities of anchor action. We focused on NHS organisations, which acted as local convening partners. However, we also wanted to hear from other place-based partners, often more advanced in this area, about their anchor work and how this changed during the pandemic.

153 participants from 87 organisations took part, including the NHS, local government, the Scottish government, the Innovation Unit, higher education, the voluntary and community sector (VCS) and others.

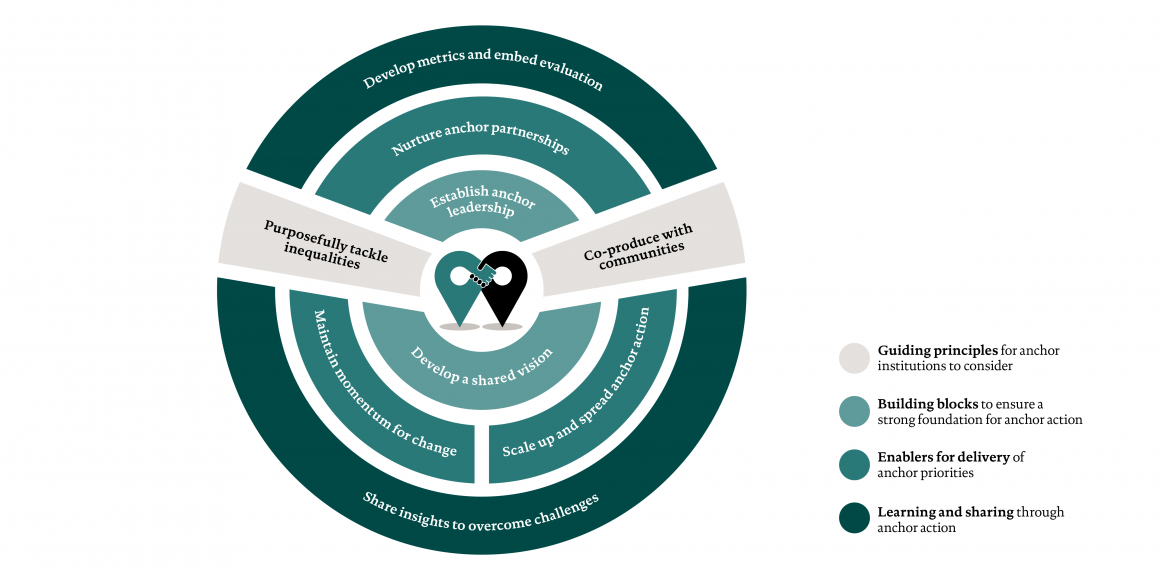

Figure 2 shows these lessons grouped into four main areas, which we also use to structure our findings.

- Guiding principles for anchor institutions to consider are important in all stages of anchor work.

- Building blocks to ensure a strong foundation for anchor action.

- Enablers for delivery of anchor priorities includes key factors to ensure anchor plans translate into sustained action.

- Learning and sharing through anchor action includes lessons for anchor institutions seeking to measure their impact or navigate national policy barriers.

These lessons may be familiar to those working in health care and improvement. However, it is important to ensure these lessons are applied intentionally to anchor approaches and addressed coherently and consistently across an area. When applied collectively, they can help anchor institutions and partnerships frame their anchor action to maximise influence and impact.

These nine lessons are complemented by case studies that highlight examples of anchor action. While many of these initiatives are at an early stage, and some were developed prior to the pandemic, they provide practical insights into the potential opportunities, enablers and barriers for successful implementation during COVID-19 and beyond.

As part of its anchor work, Mid and South Essex (MSE) NHS Foundation Trust has developed a number of initiatives to work with and understand its community better. These include an employment dashboard to support them in widening access to work and measuring and tackling inequalities. This combines hospital data (including the roles and demography of staff and vacancies mapped to local deprivation), with council data (local demographics and the aspirations of young adults).

Specific programme activities were also developed, including:

- Partnering with Anglia Ruskin University to conduct ethnographic research to inform future recruitment and staff support strategies. This was carried out with staff living locally who are impacted by deprivation or who have informal caring responsibilities.

- Partnering with Essex County Council to commission career workshops, online mentoring and coaching, and hospital work experience for students from schools in Basildon.

COVID-19 has delayed some implementation but it has also created stronger local partnerships and increased the willingness to act on inequalities. Recruitment for a new COVID-19 vaccination hub has targeted local unemployed people. Since August 2020, 45 students from Basildon have joined the online support platform. Baseline data have been collected for the workforce dashboard and progress is due to be reported in March 2021.

MSE also reflected that:

- Partners engaged more when they saw activities happening rather than being discussed.

- Starting small projects shows what can be achieved before engaging partners in an executive-level conversation.

- Using local data is key to identifying areas of opportunity and potential impacts for the programme.

- Health sector programmes can benefit from support, knowledge, and resource from outside the system.

- Relationship building takes time but is quicker where trust already exists.

Advice to others

‘Get hold of your in-house and council data and discuss it with local staff and leaders to identify pain points and opportunities for impact. Enhance current data rather than gathering more data and use data which people recognise and can help visualise a problem differently – for example, the geospatial mapping really engaged local nurses.’

For further information please contact Preeti Sud (Head of Strategy Unit) and Charlotte Williams (Director of Strategy).

Across our conversations, many participants acknowledged the substantial impact COVID-19 is having on staff health and wellbeing. This includes increased levels of burnout and sickness absence rates, as well as concern over the risk of ‘moral injury’ and sustained longer term repercussions.

Supporting and protecting staff both physically and psychologically was recognised as a key priority in the third phase of the NHS response to COVID-19. Before the pandemic, the Royal Free Hospital found that co-designing health and wellbeing initiatives with facilities staff led to a significantly lower rate of sickness absence. This is likely to be equally relevant during both the response and recovery phases of COVID-19. Participatory approaches can contribute to an increased sense of value, belonging and empowerment among staff.

The Building Better Places programme has used capital investment in new hospital buildings as a catalyst for wide-ranging economic and social revitalisation for communities across the Humber region.

The programme brings together partner anchor organisations (including the NHS, local authorities, LEPs, universities and major employers) to develop an investment proposition spanning the area’s economy, health care services, buildings, workforce, digital infrastructure, sustainability, research and development, and long-term prosperity.

Different partners have led on different aspects of the work – for example, one local authority partner led on the production of an economic and social impact study, while two universities are developing a research and development collaborative.

The Humber Coast Vale Partnership reflected that:

- Demonstrating impact was challenging – any built assets may not be evident for another 10+ years; and the wide-ranging community benefits, not for many years after that.

- The partnership has improved and continues to develop – drawing together public and private organisations from different sectors, with COVID-19 acting as a catalyst.

- It was important to find commonality across the broad range of visions and ambitions from individual organisations.

- Building relationships with key stakeholders in a wide range of sectors was a good starting point and helped to more easily ‘sell’ the vision.

Advice to others

‘Hard work, dedication, cooperation and – most fundamentally – a clear shared vision to aim towards are key. Take the time to develop relationships and figure out who you need to have around your virtual table. Working with good humour, at a time when traditional ways of working have been turned on their head has also been pretty important.’

For further information please contact Humber, Coast and Vale Health and Care Partnership.

In many places, the urgency of responding to COVID-19 is providing a strategic lens through which to further develop a shared anchor vision and narrative. Priority areas highlighted in our discussions included workforce recruitment and retention, expansion of inclusive digital services and investment in research and innovation.

Collaborative Newcastle is a partnership aiming to improve the health, wealth and wellbeing of everyone in the city. Partners include the local council, NHS clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), NHS foundation trusts, primary care networks (PCNs), GP services, and the voluntary sector.

The region and partnership managed to secure funds to develop the Integrated COVID Hub North East (ICHNE), which aims to transform COVID-19 test and trace capabilities in Newcastle, while creating 1,100 new local public sector jobs. Local leads reflected that this was achieved through mutual trust, cooperation and open communication between the collaborative partners.

There has been a strong focus on targeting areas of deprivation and ensuring inclusive and local recruitment. Jobs are advertised with flexible working times, and no previous training or qualifications are required. Applicants from ethnic minority backgrounds were encouraged to apply, as well as those living with disabilities, those who lost employment during the pandemic or beforehand, and students including those on sandwich years. The hub provides education, training and career progression to support employees.

Of 700 staff appointed by January 2021, 18% came from minority ethnic backgrounds, 12% LGBTQI+ and 8% of those employed said they were living with a disability (all significantly exceeding comparable statistics for the hospital trust).

Advice to others

‘Think big and don’t be constrained by normal thinking or fear of failure. We could have chosen equipment for the labs that would have required fewer staff and provided fewer employment opportunities. We had no track record in recruiting at this scale and speed, but we were determined to stick with our ambitious targets for job creation. It was the right call; the scale of the opportunity really motivated everyone involved to make it happen and the recruitment process has been a great success, despite the challenging timescales and COVID-19 restrictions.’

For further information please visit: www.collaborativenewcastle.org or www.careers.nuth.nhs.uk/your-career/integrated-covid-hub-north-east

We also heard that system constraints, such as siloed commissioning, workforce pressures, and differing performance indicators, as well as a culture of competition were slowing some anchor partnerships. In addition, some local authority participants engaged in anchor-like work over the longer term shared frustrations that the health sector was positioning itself as ‘leading’ anchor action without acknowledging or learning from local government work.

‘We’re pushing at an open door in terms of the principles, the vision and the philosophy, the reality of delivering it and actually making it happen is incredibly difficult… we’ve got a lifetime of competition between our organisations which is really detrimental to this agenda.’ (CCG Chief Finance Officer)

In each conversation, we asked participants anonymously to use one word to describe their local partnerships (Figure 3). While there were a range of responses, many felt that partnerships were at an early stage and still emerging or fragmented. Despite this, there was almost universal agreement that COVID-19 has accelerated and strengthened local partnerships, and there was optimism that further progress was possible.

Figure 3: One word to describe how local partnerships for anchor strategies are working

Lesson 6: Maintain momentum for change

Due to the detrimental impact of COVID-19 on health and widening inequalities, there was a consistent view that anchor action needs to happen at speed. Some felt that progress had been made in recent months that previously would have taken years. This was attributed to an increased sense of urgency to improve health, the temporary relaxation of bureaucratic processes, and increasing partnership working during the pandemic.

‘It would be good to keep up a spirit of innovation and testing our ideas quickly, as we have done throughout the pandemic. Many barriers perceived are not real.’ (Chief Executive, local council)

During and beyond the pandemic, anchor institutions and partnerships will need to consider how to maintain energy and the pace of change while demonstrating impact, and incorporating learning.

Quality improvement (QI) approaches could help in responding to this challenge by providing systematic and consistent methods with specific techniques to improve quality and learning. Testing new ideas in small cycles can help ideas to evolve and turn theories into knowledge, while maintaining momentum, as described in case study 4.

East London NHS Foundation Trust (ELFT) are incorporating QI approaches to develop and test new social value metrics to ensure the money they spend delivers the greatest economic, social and environmental benefit for local communities.

ELFT’s social value priorities include:

- ensuring suppliers pay the Real Living Wage

- creating employment opportunities for local people

- strengthening local supply chains

- reducing environmental impact and increasing sustainability.

Progress has been made by benchmarking and analysing the current procurement process. ELFT are developing draft social value metrics based on feedback from local suppliers. Final drafts will then be tested with a small number of upcoming tenders. This will follow the plan, do, study, act cycle and will facilitate multiple trials of smaller scale changes. Embedded in this is the ability to assess impact concurrently and to build on learning from earlier cycles, prior to widespread implementation.

Despite delays due to COVID-19, procurement from local suppliers increased from 35% in April 2020 to 48% in September 2020, and there has been an increase in the proportion of contracts that stipulate employees must be paid the Real Living Wage.

ELFT reflect that the work has benefitted from supportive leadership and staff, and a strategic fit with ELFT’s values. They report the main challenges as: ensuring sufficient resource, monitoring and evaluating the work, and managing the tension between supporting local SMEs and maximising social value. For example, it was been a challenge to find ways to avoid overly bureaucratic bidding processes which may better capture social value but also likely favour larger multinational companies.

Advice to others

‘This work can only happen with full engagement from your procurement team – put in the groundwork to ensure you have their support and they are fully bought into the agenda. It’s important just to start and make small changes; organisational buy-in to the work is key as well.’

For further information please contact Stephen Newton, Head of Procurement (Commercial Development Directorate) East London NHS Foundation Trust.

Lesson 7: Scale up and spread anchor action

Local leaders were keen to scale up anchor action from isolated projects to organisational and system wide approaches. Incorporating anchor concepts into decision making and standardised processes can help to ensure scaling up within the organisation. For example, Dorset County Hospital is developing a Social Value Impact Assessment Framework that will be incorporated into all trust policies and business planning processes.

We also heard how anchor action can take place at multiple levels: individual institutions, local places, PCNs, ICSs, cities and regions. Some areas are taking a broad approach and actively including smaller or different types of institutions, such as VCS organisations.

‘Primary care networks are perfectly placed to be ‘anchorettes’ within their communities, but we are still in our infancy and need time to embed and build relationships.’ (GP)

Anchor institutions and place-based partnerships are increasingly collaborating at a system level through various vehicles including ICSs in England. This can support the spread practice within anchor partnerships.

‘People have been too busy measuring performance targets to do anything proactive about promoting [anchors], and I think that's what the ICS could actually do – promote this agenda... so that all the organisations believe that it does add value.’ (Chief Executive, VCS).

NHS London has started to develop a London-wide anchor network that aims to help the NHS maximise its economic role at each tier in London – as an anchor city, anchor system and anchor place.

As anchor institutions increasingly work within these partnerships and networks, there are clear opportunities to both scale up and spread good practice. Due to the complex nature of this work, adopting anchor activity from other organisations or sectors can be challenging. Recognising this and allowing time for testing, revision and innovation can help ensure ideas are successfully translated into new contexts.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more