One year on: Three myths about COVID-19 that the data proved wrong

23 March 2021

About 5 mins to read

About this article

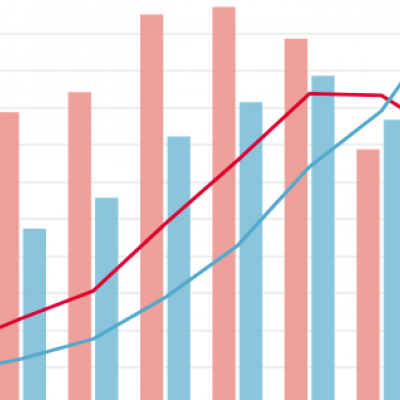

The charts in this analysis highlight three ‘myths’ that were prevalent at the very start of the pandemic. We use a common measure ‘years of life lost’ to describe what each death meant.

Key points

Myth 1: ‘Those who die from COVID-19 would have died soon anyway’

- In the first year of COVID-19 (5 March 2020 to 5 March 2021), 1.5 million potential years of life were lost in the UK as a result of people dying with the virus. In England and Wales alone this figure is 1.4 million.

- On average, each of the 146,000 people who died with COVID-19 lost 10.2 years of life.

Myth 2: ‘It’s just a bad flu season’

- In a bad flu year on average around 30,000 people in the UK die from flu and pneumonia, with a loss of around 250,000 life years. This is a sixth of the life years lost to COVID-19.

- We have more detailed data for England and Wales. This shows us that, even looking only at those aged older than 75 (who account for most COVID-19 and flu deaths) – COVID-19 has been much more deadly. In 2018, a bad flu year, around 25,000 people older than 75 died from flu or pneumonia. These people lost a total of 140,000 years of life – 5.75 years each on average. This is about a quarter of the life years lost among those older than 75 from COVID-19.

- More years of men's lives have been lost in the pandemic than women’s. Again, looking at England and Wales, women older than 75 lost around four-times more years of life than for a bad flu season; for men it was five times higher.

Myth 3: ‘COVID-19 is the great leveller – we are all equally at risk’

- COVID-19 was not the great leveller. People in the 20% most deprived parts of England were twice as likely to die from COVID-19 as those in the least deprived areas. They also died at younger ages, so may have lost more years of life. While existing health inequalities mean these people may have had lower life expectancy, the analysis found that in total, 35% more lives were lost in the 20% most deprived areas than the least, with 45% more years of life lost in total.

- On average, each person who died in the most deprived quintile lost 11 years of their life, compared with 10 years in the least deprived.

Further reading

One year on: Three myths about COVID-19 that the data proved wrong

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more