Monitor’s Chief Economist, Chris Walters, discusses their latest analysis of clinical workforce shortages in England.

You may have asked yourself this question if you’ve read the National Audit Office’s recent report on the supply of clinical staff in England. Our latest analysis of clinical workforce shortages sheds light on this, revealing a chain of unintended consequences.

The push for higher nurse to patient ratios following the Francis report in 2013 caused demand for nurses to increase.

But supply at NHS wage rates didn’t keep pace and the resulting shortage pushed hospitals into the agency labour market, where wages were uncontrolled. Rates for agency nurses unsurprisingly shot up – by 30% over three years – exacerbating the sector’s financial fragility.

Today hospitals estimate they are still 15,000 nurses short.

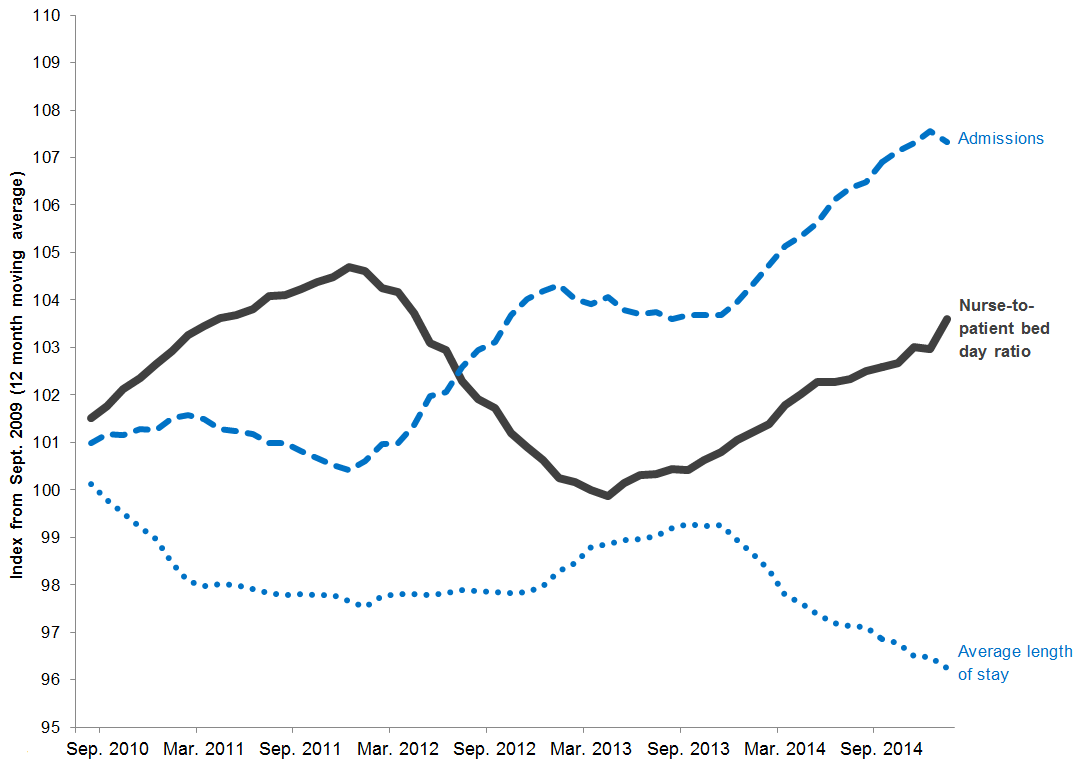

Trends in nurse-to-patient ratio, admissions and length of stay 2010 to 2015

Our analysis also reveals a success that deserves attention. Current nurse shortages would be a lot worse had hospitals not dramatically reduced the length of stay over this period, as shown by the downturn in the dotted line below.

This was achieved even with a sharp rise in admissions (see the upturn in the dashed line). The upturn in the solid line shows hospitals did this without diluting the ratio of nurses to patients.

This means hospitals can treat larger numbers of patients without diluting the care they provide.

Had hospitals not reduced length of stay they would need an additional 5,000 nurses – one for every ward in England – costing the NHS another £250 million at agency rates.

The NHS is a huge employer: directly employing over 640,000 clinically qualified people, including 110,000 doctors and about 315,000 nurses. The majority of a typical hospital’s costs is on people. So smooth functioning of the market really matters to the quality of NHS care and the sector’s financial sustainability. The zig-zag line above is a tell-tale sign of supply and demand being out of kilter, ramping up the challenges of providing high quality, good value patient services.

As Monitor’s Chief Economist, I asked myself: does the market for NHS clinical staff have to be this way?

The causes aren’t hard to find. First, the supply of clinical staff can only respond sluggishly to changes in demand because we plan it so far in advance. To turn out nurses and doctors central bodies forecast future demand and then arrange the right number of taxpayer-funded training places. But it takes at least three years to train a nurse and at least 10 for a doctor, so it’s very difficult to get the supply/demand balance right.

Historically, we’ve looked abroad to fill clinical workforce shortages. In fact an important contributor to recent shortages has been a collapse of nurses from outside the European Economic Area (EEA). Numbers have fallen by 95% from a peak of over 15,000 a year in the early 2000s.

But could we not grow more of our own?

In other professions, individuals shoulder the risk of finding a job after they train, with success depending on the ebb and flow of demand after graduation.

So should clinical professions be entirely different?

University courses for nurses and doctors are the most oversubscribed in the country. Were tax payer support to be reduced, it would need a dramatic aversion by aspiring students to paying towards their own training to choke this unmet demand. In the decade since tuition fees were introduced for other subjects this hasn’t happened. The University of Bolton already charges fees to student nurses and its course was oversubscribed in September 2015. Perhaps the announcement by the health minister in December 2015 of the replacement of nursing bursaries with student loans is a first step towards this.

Another reason it’s hard for central workforce planners is the unpredictability of demand. Policy changes can cause sudden unexpected ‘demand shocks’. How could planners account in advance for the immediate impact of the Mid-Staffs inquiry on nursing demand? This characteristic of demand might be hard to change. But economic techniques could model the impact of policy changes before they are rolled out nationwide enabling us to pinpoint the risks and mitigate them in advance. Had we done this when the Francis report published, would we have restricted immigration of nurses from outside the EEA? Another option is to train clinical staff to work more flexibly to smooth out these shocks.

Lastly, in other markets, including those for professionals, changes in price help bring supply and demand back into balance. When trained professionals are scarce, they raise their rates, attracting others to the profession, so supply increases. Likewise, when wages rise, employers want fewer professionals as they are more expensive, so demand falls. In this way, changes in wages balance supply and demand. But wages for clinical professionals are centrally controlled, so this doesn’t happen automatically in the NHS market.

These wages may be regulated for good reasons but one inevitable consequence is that unregulated wages in the temporary ‘overflow’ markets – such as market for agency nurses and locum doctors – have been highly volatile.

The reason for this volatility will be familiar to anyone who’s bought a scalped ticket to see their favourite band. Venues can put on only so many performances. Fans’ demand outstrips this. Bands keep ticket prices down so that real fans can afford them. Something has to give: the pressure pops up in tickets sold on at prices far in excess of face value. The websites that match these ‘secondary’ buyers and sellers take a cut. Half of agency nurses and locum doctors are NHS employees reselling themselves to hospitals, with agencies taking a cut. The same economic forces apply. To address these forces the Secretary of State for Health announced a cap in October 2015 on how much hospitals can pay per shift to help control spending on agency staff. But maybe it’s time to look at what we can do differently upstream to manage the supply of clinical staff more effectively.

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more