NHS winter pressures: Being in hospital

5 January 2018

This is the third blog in a Health Foundation series looking at winter pressures in the health and social care system in 2017/18. In the first blog, Dr Becks Fisher looked at how the NHS is aiming to help us stay well and reduce pressure on hospitals. In the second blog, Tim Gardner explored what is happening at the front door of hospitals. In this blog, Anna Starling writes about what’s happening inside hospitals in England.

During winter, the media often focuses on patients waiting in an ambulance or inside the emergency department. The first few days of 2018 also brought news of winter pressures affecting routine operations. So what does winter mean for those who need a hospital bed for planned or emergency care?

Critical care capacity

The most critically ill patients in hospital this winter will require a critical care bed for advanced support and close monitoring. These beds contain sophisticated monitoring equipment and there is normally one nurse for every one or two patients. Adult, paediatric and neonatal intensive care have different staffing and equipment needs, but bed capacity for all three groups of critical care patients has grown slightly over time according to national data on available critical care beds in England. This is in contrast to the fall in overall acute bed numbers, which is discussed below.

What this does not tell us, however, is whether capacity has kept pace with need. Critical care beds and equipment are finite resources, and the specialist care needed by critically ill patients also creates particular staffing pressures. In some cases, there may be a physical bed ready, but it cannot be used because not enough staff with the right skills are available.

The difficult decisions that hospital staff have to make to manage demand are not shown in the data. These decisions include delaying planned operations for patients who are likely to need critical care post-operatively, if critical care beds are under pressure from winter-related admissions. This is likely to contribute to growing waiting lists for elective treatment. The increased rate of flu-related admissions to critical care this winter compared to this time last year will place further pressure on these beds.

General bed occupancy

Most patients in critical care will eventually require a standard ward bed. The number of hospital beds in England has been falling since at least the 1980s, if not earlier. This has largely been facilitated by shorter hospital stays and the development of less invasive medical procedures. But the number of hospital beds is no longer keeping pace with demand.

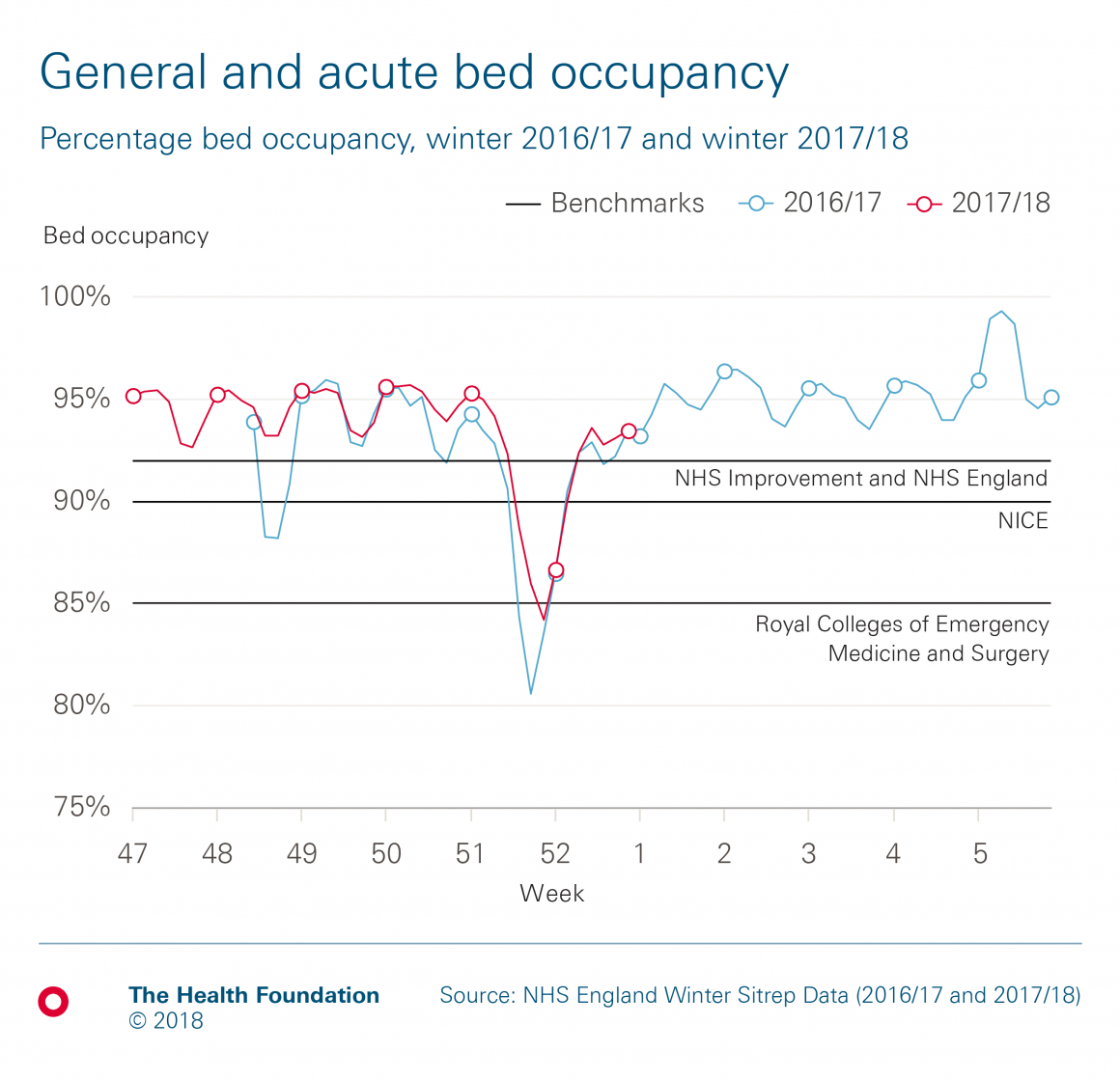

This has led to more pressure on existing beds. The NHS measures pressure on beds through ‘bed occupancy’, meaning the percentage of beds in a hospital that are occupied by patients. Nationally, bed occupancy levels for general and acute care are now at the highest level since current records began in 2010. For the last 3 years, the average occupancy level has been above 90% between January and March. Since 1 December 2017, average occupancy has been 93.1%, compared to 91.9% over the same period last year. Over the first 6 weeks of winter this year on average 70% of hospitals have had a bed occupancy level over 92%.

These high occupancy levels are a concern. NHS Improvement and NHS England have recommended that occupancy should be kept below 92% to support patient flow through hospitals this winter. The Royal Colleges of Emergency Medicine and Surgery have contested this 92% target, stating that 85% would be a better bed occupancy benchmark to ensure the safety of patients.

In draft guidance on emergency and acute medical care in adults NICE has reviewed the evidence on occupancy rates. This guidance highlights the risks of adverse outcomes associated with increased occupancy rates, such as avoidable health care associated infection.

It advises that occupancy rates above 90% should be viewed with concern. NICE does however warn that this figure should be treated flexibly: for example, occupancy levels may be safely higher in effectively run wards for patients undergoing elective care and lower where there is evidence that harm was associated with a higher occupancy rate.

While there is disagreement about what percentage occupancy is safe, there is consensus that the current high levels of occupancy are a symptom of unsustainable pressure on hospitals.

Finding the right bed at the right time

As Tim Gardner described in our second winter pressures blog, a lack of available beds creates longer waits in emergency departments. To cope with this, many hospitals are forced to find patients beds in wards not specifically set up for their conditions. These patients are commonly referred to as ‘outliers’.

For example, a patient with a respiratory problem might be placed on a ward for patients undergoing surgery. The patient is further removed from those who are specialists in their care, and it creates additional pressure on clinical teams who are required to care for patients across multiple wards.

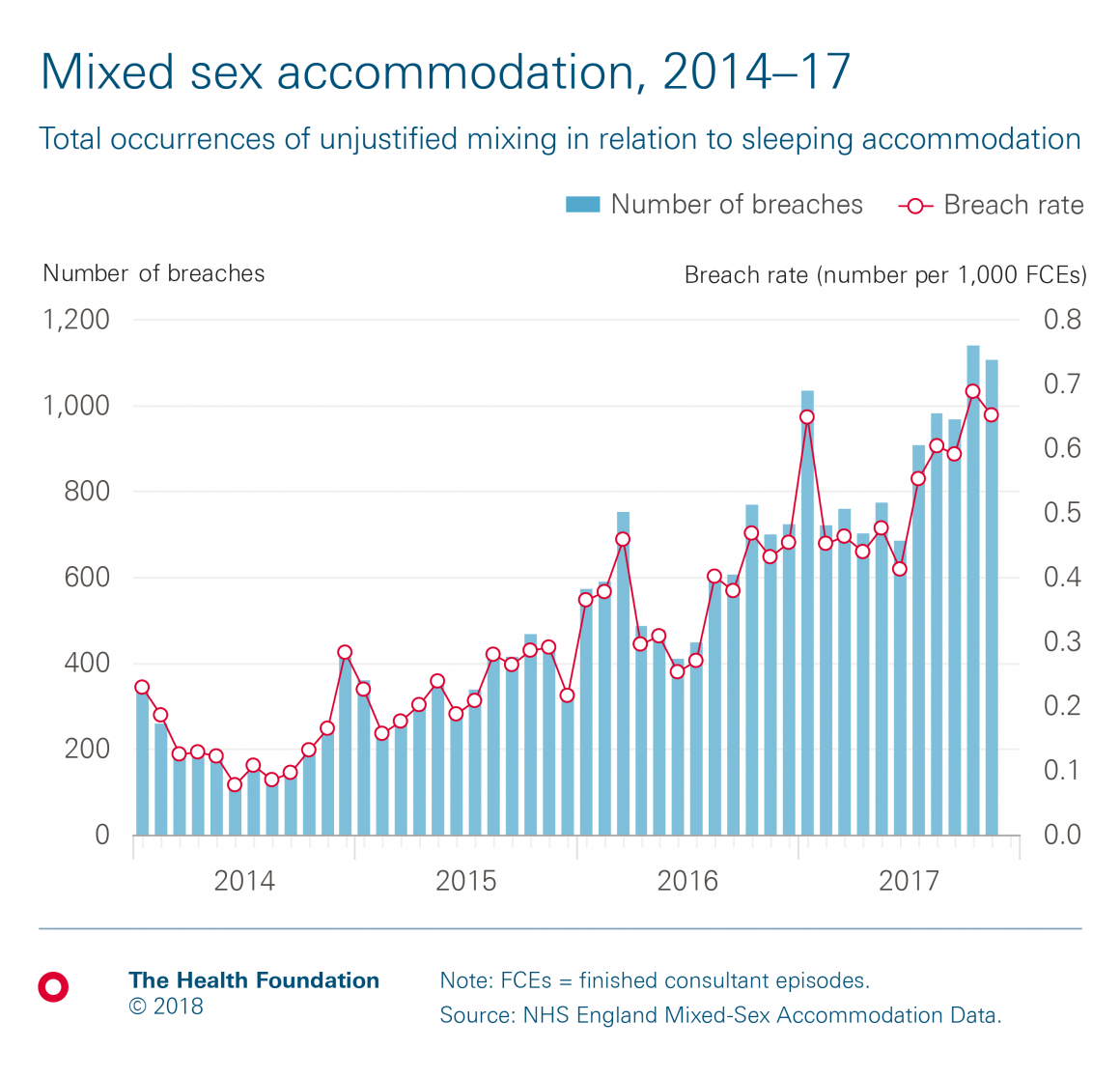

While there are no national data currently available on the number of outliers, the growth in breaches of the NHS mixed sex accommodation policy is an indication that finding the right bed at the right time is proving increasingly difficult. Given the recent recommendation from the NHS National Emergency Pressures Panel for CCGs to temporarily suspend sanctions for mixed sex breaches, we may see these rise further this winter.

Opening and closing beds

Some hospitals open additional beds to help with this pressure. Between December 2016 and February 2017, there were on average 3,659 additional general and acute beds open every day across England – up from 3,466 in 2015/16. As John Appleby has previously pointed out, this equates to opening more than five additional hospitals each day. As of 1 January 2018, 2,615 beds have been opened on average per day compared to 2,601 beds per day over the same period last year.

Opening extra beds puts an additional load on an already stretched workforce. The Health Foundation's recent report, Rising pressure: the NHS workforce challenge, found that decreases in length of stay and increases in the number of nurses in 2014 and 2015 led to nurses per bed day – a metric that can be used to identify staff shortages – recovering to almost the same level as in 2011. However, data from 2016 onwards suggest that as admissions are continuing to rise, nursing numbers are not. Winter peaks in sickness absence for all hospital staff further exacerbate this situation.

While some beds open, others close. Highly contagious vomiting bugs like norovirus, which is more common in winter, affected 682 beds per day on average last winter – of which 145 beds were closed to prevent further spread (the remainder were occupied by patients with norovirus-like symptoms). So far this winter, vomiting bugs have affected on average 901 beds per day compared to on average 844 beds per day over the same period last year.

Hospital pressures and quality of care: Are there any warning signs?

It is difficult to know from the data alone how hospitals being much busier may be affecting the quality of care for patients. High levels of bed occupancy are associated with higher rates of health care associated infections, such as MRSA and Clostridium difficile, but these currently remain at very low levels. Beyond this, there are very little national data about how pressures on hospital capacity may be directly affecting the quality of care for patients in hospital.

Big factors in preventing the quality of hospital care deteriorating include the commitment and professionalism of staff. But it is these very staff who warn that the demands placed on them in winter months are becoming untenable.

Given the winter pressures on hospital beds, there is an understandable focus on ensuring that patients can be discharged as soon as possible. In our fourth blog in this winter series, we examine the efforts taken to make sure that no-one is kept in hospital longer than necessary.

Anna Starling (@AnnaStarling) is a Policy Fellow at the Health Foundation

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more