We need a coherent approach to our NHS workforce woes

30 July 2018

What is clear is that the recently agreed increase in NHS funding cannot deliver improved services without the staff in place to make it happen.

The most recent data on the NHS workforce in England published late last week shows that vacancies for nurse and midwife posts continue to be at a historically high level with 34,700 vacancies advertised in the first quarter of this year. This is 5% more than the same period last year. Previous analysis showed that, despite rising demand pressures, the number of nurses barely grew between 2010 and 2017. The latest figures reveal that, once again, there has been almost no rise in the number of nurses, including in priority areas such as mental health.

In large part, these shortages have been of our own making, reflecting a lack of coherent national workforce planning and funding, exacerbated by a migration policy regime that has severely dented the UK's ability to recruit nurses and other health professionals from other countries. Brexit concerns amongst EU nurses are also now playing a part.

There are almost 700,000 nurse and midwives on the UK professional register, the ‘pool’ from which all employers must recruit. It has not grown in the last four years and one in five is aged 56 or older.

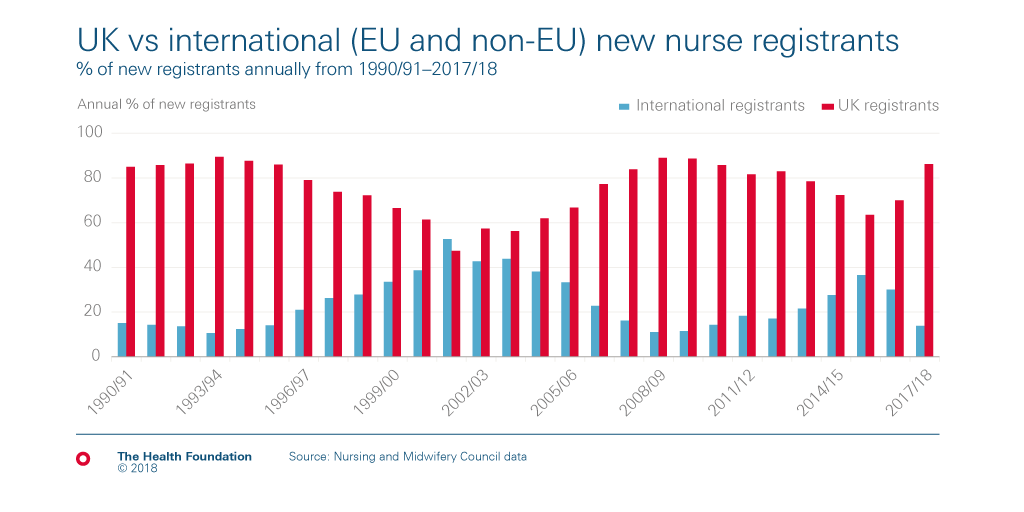

More than 100,000 of those nurses, one in seven, were trained in another country. International recruitment of nurses has always been a method used by the NHS to meet its nursing needs. A long-term perspective, illustrated below, highlights that at least one in every ten new nurses entering the UK register every year (and who are therefore eligible to practice) has come from another country. In most years this percentage inflow from other countries has been much higher – up to 50:50.

The recent drop in international inflow of nurses, as shown, does not reflect a lack of recruitment interest from UK employers. It is the result of a triple whammy:

- the ‘hostile environment‘ approach from the current government to UK immigration, which prevented many non-EU nurses and doctors entering the UK to practice, and which has now been suspended after a campaign led by the British Medical Journal;

- controversial changes in the regulatory requirements for English language testing (now partially reversed);

- and the Brexit vote in mid-2016, after which there was rapid decline in the number of EU based nurses registering to practice in the UK.

The following chart shows the year-on-year number of nurses from the EU and from other international sources who have registered in the UK since 1990. This has ebbed and flowed across the period, rising notably at the beginning of last decade when the NHS actively recruited thousands of nurses from India and the Philippines to support workforce expansion. More recently there was a surge of recruitment from the EU countries of Portugal, Romania, Spain and Italy. However, since mid-2016 the EU inflow has crashed, and whilst the non-EU inflow has increased, it has not been at a pace to compensate for the drop in EU nurses.

Month-on-month inflow of EU nurse registrants over the last two years is shown below. The sharp drop occurred in mid-2016, at the time of the Brexit vote, and has since remained stubbornly below a hundred a month.

Polling conducted by Ipsos MORI in 2018 for the Health Foundation shows that most UK adults (71%) think the UK should continue to try to attract nurses from the European Union after the UK leaves the EU, even including almost two thirds (65%) of those who voted ‘leave’ in the EU referendum.

The drop in international nurses would be less concerning if it was the result of a deliberate policy linked to increased UK based training of nurses. There is no evidence that such policy coherence exists. The actual number of student nurses being trained in England has not increased, and ‘self-sufficiency’, if this means ending reliance on international recruits, is unlikely to be achievable in the foreseeable future given current high vacancy rates, the ageing nursing workforce, and retention indicators showing no substantial improvement.

The Department of Health and Social Care in England has recently announced a new advertising campaign marketing nursing as a worthwhile career. Positive images may help, but they need to match the reality on the wards and in the primary care centres. What is required, and what has been missing, is a joined-up and strategic approach to international recruitment of health professionals. This should involve government health departments, the Home Office, regulators and employers, and be embedded in overall national health workforce planning.

Professor James Buchan is a Senior Visiting Fellow at the Health Foundation and an international expert on health care workforce policy

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more