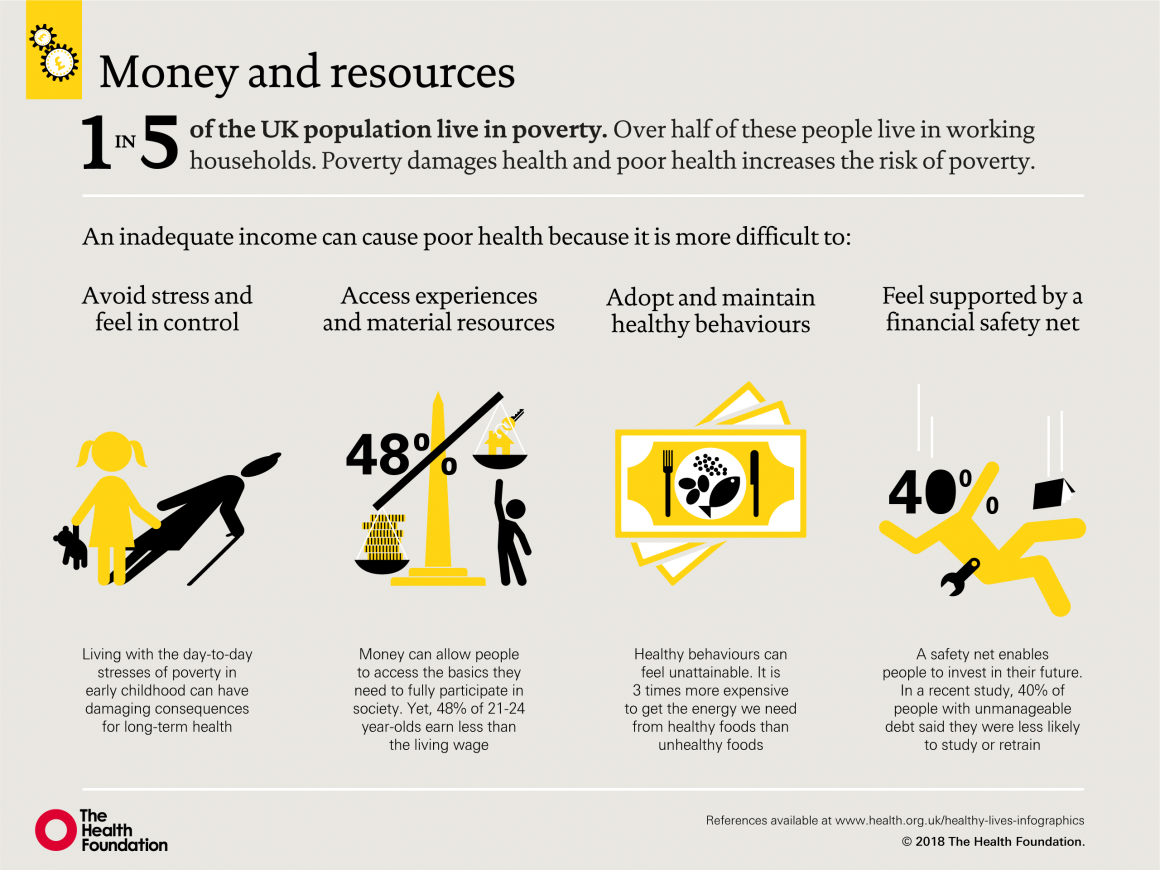

Poverty and health How do our money and resources influence our health?

30 January 2018

‘I just want to be able to live, you know, I don’t want to just survive.’

This extract, from a Joseph Rowntree Foundation study, reflects the reality for one family trying to get by on a low income. One in five people in the UK are in poverty, without the resources to meet their minimum needs.

Money can’t buy you happiness, but it can certainly make life a lot easier. From the places we live, to the food we buy, and how we travel, money is often a factor. Our latest infographic looks at how poverty can influence health.

We want our series of infographics to be a useful resource to help change the conversation about what makes us healthy. You are welcome to download, save and share them for education and non-commercial use. Please make sure that no modifications are made and that the Health Foundation and the source is clearly acknowledged in full.

If you have any further questions about using our resources in your work please get in touch at website@health.org.uk

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s UK Poverty 2017, shows that over half of people living in poverty are in working households and many are in vulnerable groups. Too often, work doesn’t pay enough or people fall into poverty through circumstances beyond their control. Poverty is, in part, about lacking basic material resources. People are struggling to put food on the table and a recent review by housing and homelessness charity Shelter found that one in every 200 people in the UK is homeless.

But it’s also about exclusion and missed opportunities – the child who is singled out for having free school meals or the person who misses a job interview because they don’t have the ‘right’ clothes. When people are prevented from accessing resources and experiences, it can compromise their ability to participate and feel valued and included in society.

How does poverty affect health?

The healthy life expectancy gap between the most and least deprived parts of the UK is 19 years. The reasons for this are complex and money is just one part of the picture – the index of multiple deprivation also includes other determinants of our health such as housing, employment and education. Yet, in many conversations I have about inequalities in health, ‘deprivation’ or ‘disadvantage’ are quickly translated into ‘poverty’. While we mustn’t lose sight of the other factors involved, the importance of having enough money cannot be ignored.

An adequate income can help people to avoid stress and feel in control, to access experiences and material resources, to adopt and maintain healthy behaviours, and to feel supported by a financial safety net. Through these mechanisms, people are more able to access the opportunities needed for a healthy life. These opportunities include meaningful work, secure housing and high self-esteem – all of which affect our long-term physical and mental health.

The relationship also works in the other direction. Good health can enable people to access social and economic opportunities, such as secure and good quality work. Without these opportunities, people can become trapped in cycles of poor health and poverty.

Poverty constrains choice

There is much debate about the balance between individual 'lifestyle' choices versus wider structural factors in shaping our health. It’s true that individuals can have agency over decisions that affect their health, but this agency can be severely limited by poverty. Decisions to buy unhealthy food, cigarettes, or a TV should be viewed in this wider context.

The novelist James Baldwin put it well when he said ‘anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor’. While the links between cold, damp housing and poor health are well known, prepaid energy meters can mean people on low incomes need hundreds of pounds more to meet energy costs each year. This can be a challenge for many of the 48% of those aged 21–24 who don’t earn the living wage. Similarly, our infographic shows that it can be three times more expensive to get the energy we need from healthy foods than unhealthy foods.

Poverty also expends emotional resources, and affects people’s ability to comprehend the future. Viewed through this lens, it’s possible to see how unhealthy behaviours such as smoking are used as quick fixes in stressful circumstances. Or how, if you’re suffering with loneliness and on a low income, buying a TV is not as unwise as it might seem. Poverty also limits people’s ability to invest in the future and thereby improve their future health prospects. Studying, retraining or moving to a new city can open up valuable opportunities, but without a financial safety net, the risks are simply too high for many people.

Tackling poverty to improve health

There are many stories of people overcoming a lack of money, perhaps through getting a place at a school or college, or using a talent in music or sport. But given the scale of the problem, a few ‘golden tickets’ is not the answer. Tackling poverty requires cross-sectoral action. Education and skills, good work, a benefits system that responds to need, debt support, and tighter gambling laws all have their part to play.

As Liverpool Councillor Richard Kemp highlights in our recent publication Policies for a healthy life: a look beyond Brexit, we must seize opportunities to develop ‘more aggressive policies to encourage the creation of wealth across the country’, and in doing so address inequalities across society as a whole.

The moral and economic case for action is huge. £1 in every £5 of all spending on public services is needed because of the impact and cost that poverty has on people’s lives. A UK in which more people are living, and not just surviving, requires a more ambitious approach – one that responds to the experiences and priorities of the 1 in 5 people who understand the issues best.

Sarah Lawson is a Policy and Programme Support Officer in our Healthy Lives team.

References

- One in five people don’t have the resources to meet their minimum needs

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. UK Poverty 2018. 2018.

Available from: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/uk-poverty-2018

- Living with the day-to-day stresses of poverty in early childhood can have damaging consequences for long-term health

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Psychological perspectives on poverty. 2015.

Available from: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/psychological-perspectives-poverty

- It is three times more expensive to get the energy we need from healthy foods than unhealthy foods

Jones et al. The growing price gap between more and less healthy foods: Analysis of a novel longitudinal UK dataset. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109343.

Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4190277

- 48% of 21–24-year-olds earn less than the living wage

Office for National Statistics. Proportion of employees earning below £8.75 per hour working outside London, £10.20 per hour working in London: April 2017. 2017.

Available from ONS website

- 40% of people with unmanageable debt said they were less likely to study or retrain

Citizens Advice. A debt effect? How is unmanageable debt related to other problems in people’s lives? 2016.

Available from CAB website

- Why do people in disadvantaged circumstances tend to have poorer health at most stages in life?

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. How does money influence health? 2014.

Available from: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/how-does-money-influence-health

Related blogs

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more