Why we need to rebalance children’s services spending to invest in a healthier future

28 October 2019

The 2019 Spending Round ‘turned the page on austerity’, providing a real-term boost for day-to-day government spending. But simply increasing current spend won’t reverse the impact austerity has had on the effectiveness of government services. As our recent report Creating healthy lives showed, there has been a clear shift in funding away from prevention, in areas that create and maintain people’s health, towards reactive services tackling the most acute needs.

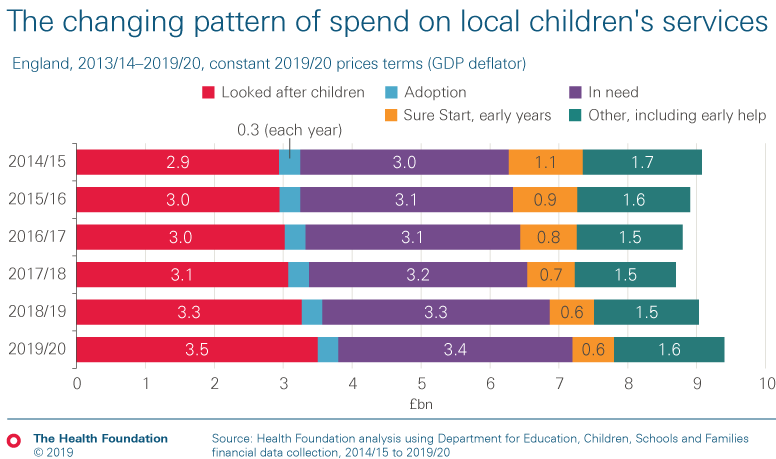

The latest Department for Education data on children’s services provides a prime example. Funding for children’s services increased to £9.4bn in 2019/20, representing a 4% real-term increase from the previous year, and surpassing the previous peak in 2014/15 (the earliest data available on a consistent basis). However, as the chart below shows, there has been a significant reallocation to reactive statutory services instead of proactive early years prevention.

Looked after children

A child who has been in the care of their local authority for more than 24 hours is known as a looked after child. Looked after children are also often referred to as children in care. (Source: NSPCC)

In need children

Children in need are defined in law as children who are aged under 18 and:

- need local authority services to achieve or maintain a reasonable standard of health or development

- need local authority services to prevent significant or further harm to health or development

- are disabled

(Source: Citizens Advice)

Early years

This refers to learning, development and care for children from birth to five years old. It includes services such as Sure Start centres.

Early help

Early help, also known as early intervention, is support given to a family when a problem first emerges. It can be provided at any stage in a child or young person's life. (Source: NSPCC)

Local authorities in England have a statutory responsibility to safeguard the wellbeing and safety of children. If a child is at risk of harm or needs further support to achieve a reasonable level of health and development (for example, if they have a disability and need extra support), they are classified as 'children in need' following an assessment with their local authority. In cases where there is a substantial risk of harm, local authorities may use their statutory powers to take children into care or place them for adoption. These three categories – in need, looked after and adoption – represent provision for the most acute need, and accounted for around 77% of the overall children’s services spending in 2019/20, up from 69% in 2014/15.

Local authorities may also fund preventative non-statutory early years services, such as Sure Start. Since 2014/15, funding allocated to these services has almost halved from £1.1bn to £0.6bn, despite the long-term benefits they bring to children, communities and the wider economy.

Local government services play a very important role in supporting children’s physical, social and mental development. Long-term investments in key services can improve children’s health – now and in the future – through improving their school-readiness and attainment, and ultimately their employment prospects.

What is driving the shift towards reactive spending?

While the case for early intervention is well-known, there are two key factors driving the shift towards reactive spending, in a period in which overall budgets were initially being cut.

The first factor is that cases of activity in children’s social care have increased. At the end of March 2017/18, there were 404,710 children in need, up by 14,580 children compared to 2014/15. By far the most important factor contributing to children being in need was domestic violence, followed by mental health problems, emotional abuse, neglect, and substance misuse. Many of these are issues which can be addressed by well-funded services. There were also significant increases in the most serious cases: the number of looked after children (including adoption) in England increased to 75,420 in 2017/18, up by 5,950 children compared to 2014/15.

The second factor is the cost of these services. While looked after children (including adoption) account for a relatively small proportion (19%) of all children receiving statutory support from local authorities, more than one third of the budget is dedicated towards this group. This is because the cost of services tends to increase with the level of need, with an annual cost between £566 and £5,166 per child in need episode, an average cost of £20,400 per looked after child placed in foster care, and £46,600 per looked after child with more complex needs placed in residential care in 2017/18. The lack of available placements and staff has also meant that it is more costly than before to place children in residential care.

Of course, an overall lack of investment in preventing acute need from developing in the first place can create a reinforcing circle where acute need continues to grow, placing further cost pressures on statutory services.

Why is prevention important?

Effective prevention can improve the quality of life for children and their parents. Having a better understanding of what is causing families to experience adverse outcomes and funding the services that support them at an early stage can be an effective way to help families stay together. Preventing the emotional trauma children experience when they are placed into care is another positive impact on their health and wellbeing.

A recent study indicates that providing greater access to Sure Start children’s centres in England is associated with lower hospitalisation rates by the time children reach age 11. The financial benefit of Sure Start is estimated at £65m, of which £5m is attributed to direct cost savings to the NHS from avoided infections and injuries, while the remainder is attributed to averted indirect (parental and societal) costs, and the financial impact of their consequences over the life course. The benefits from hospitalisation offset around 6% of the programme cost. More importantly, the study finds that the benefits are more pronounced in the more deprived parts of the country.

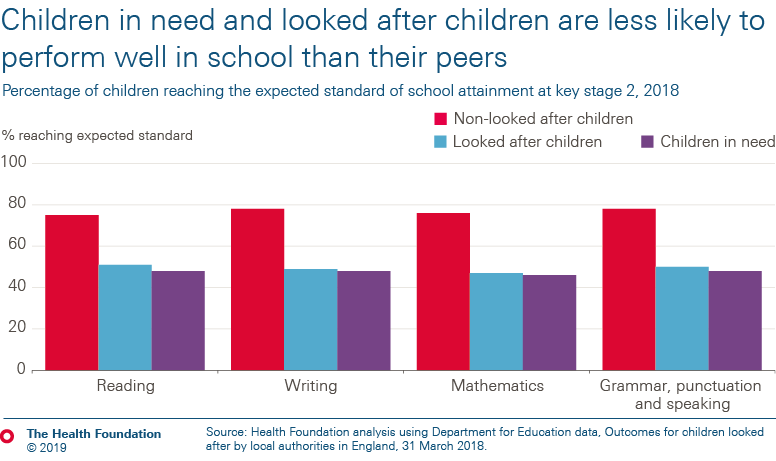

Prevention can also bring many benefits to society and the wider economy. Children in the care system who experienced severe and complex needs have poorer educational achievements and higher school absence rates than their peers. In 2018, non-looked after children were significantly outperforming their looked after and in need peers across key academic indicators. For example, an average 75% of non-looked after children achieved the expected standard in reading, whilst only 51% of looked after children and 48% of children in need achieved this standard. These differences in attainment are also associated with long-term productivity losses in terms of employment outcomes and earnings later in life.

Funding for children’s services is just one example of a wider pattern across government to shift funding towards reactive public services and away from more preventative, early intervention programmes. With benefits often accruing in the long run, it is harder to protect such services when there are more immediate funding pressures. But with the age of austerity seemingly at an end, an upcoming general election is a key opportunity for government to commit to long-term investment in the wider conditions needed for a healthier future.

Nadya Mihaylova is an analyst in the Healthy Lives team at the Health Foundation.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more