Health and care for older adults during the pandemic What The Commonwealth Fund’s 2021 international survey reveals about the UK

29 April 2022

Key points

-

The Commonwealth Fund’s 2021 International Health Policy survey asked 18,989 older adults across 11 countries about their health and health care between March and June 2021. This included 1,876 people in the UK. The Health Foundation reports on the findings from a UK perspective.

-

This analysis draws on the survey results to offer some insight into how health and care services for older adults were affected mid-pandemic. The results show that the UK still performs strongly in protecting older people from financial costs related to health care, with the highest proportion of people reporting no ‘out-of-pocket’ costs (56%).

-

Older adults in all countries were less likely to have seen a doctor or visited A&E during the pandemic, but the survey suggests that the UK health system experienced more disruption than others in Europe. 25% of UK respondents said that they had appointments either cancelled or postponed. This is the third highest proportion after the US (33%) and Canada (28%). Those in the UK were also most likely to say they had not seen a doctor over the past year, although the UK was among the best in access to same day GP appointments.

-

The survey confirms that the UK was not alone in experiencing disruption to services, but it faces a steep challenge to recover, as the UK has a much leaner and under-resourced health and care system relative to comparable countries. The survey also illustrates the importance of expanding access to social care to reduce unmet need. Older adults in the UK were among the least likely to receive paid social care in the home and were more likely to report drawing on help from friends and family.

Introduction

Over the past 2 years, COVID-19 has brought disruption to health care systems around the world. In the UK, at the height of the pandemic, much routine NHS care was cancelled or no longer delivered face-to-face. Although services have restarted, the lingering effects of COVID-19 mean that many have not returned to full capacity and waiting lists continue to grow: by January 2022, over 6 million people were waiting for routine hospital care in England.

Establishing whether the NHS has fared better or worse compared with health care systems in similar countries has been difficult to assess, as the data available are limited and not always comparable. This analysis sheds some light on how services in the UK were affected, drawing on the wider international survey of older adults that asked people about their experiences of primary care, hospital services and care in the home.

The Commonwealth Fund’s 2021 International Health Policy survey (IHP 2021) compares the views of older adults across 11 high-income countries. The survey asked older adults about their health, access to and experiences of health and social care, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. IHP 2021 provides insights about how the UK health system performs compared with Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the US. Analysis of what IHP 2021 means for the US health system has already been published elsewhere.

IHP 2021 surveyed 18,989 older adults about their health and health care between March and June 2021. This included 1,876 people in the UK. Similar surveys were run in 2014 and 2017. For IHP 2021, participants were interviewed by telephone, both landline and mobile. For the US, people aged 60 and older were also surveyed to allow comparison with people not yet eligible for Medicare. Data were weighted to provide nationally representative samples from all 11 countries. In this analysis, we have chosen to highlight differences between the UK and other countries (or between years within the UK) only where they are statistically significant.

IHP 2021 took place during the pandemic, but the fieldwork was undertaken during a period when people in the UK had grounds for optimism. By the beginning of March 2021, the second peak of COVID-19 cases and hospital admissions was almost over. The number of patients in hospital with the virus fell from 12,894 on 1 March, to 872 on 27 May. 5,455 confirmed cases of COVID-19 were reported on 1 March, falling to below 3,000 per day by late May. The national vaccination programme was in full swing – the number of first doses administered to people more than doubled from around 20 million at the start of March, to nearly 45 million by the end of June, while second doses rose from around 844,000 to 33 million.

The UK had also started relaxing the measures imposed to control the spread of COVID-19. In England, for example, the stages of the roadmap out of lockdown were mostly implemented in line with the government’s timetable. Schools reopened from 8 March, the ‘stay at home rule’ and rules on social contact were eased on 29 March, while non-essential retail and outdoor hospitality reopened on 12 April. Indoor hospitality reopened, and all but the most high-risk businesses were allowed to reopen from 17 May.

There was still reason for caution. The World Health Organization designated Delta a variant of concern on 11 May 2021, causing the government to announce a precautionary 4-week delay to the final stage of the roadmap on 14 June. COVID-19 cases started growing again – with over 28,000 daily cases being reported by the end of June, up from just over 5,000 per day at the start of the month. The number of patients in hospital with COVID-19 was also on the rise, though the daily number of deaths within 28 days of a positive test remained relatively low.

Survey findings

The UK continues to protect people from the financial risks of ill health

All 11 countries surveyed provide a national health service or insurance-based health care, and would claim to have universal health coverage for their populations. In the US, while there are still younger adults with no health insurance, almost all adults older than age 65 are entitled to Medicare. Universal health coverage is defined as providing access to health care ‘without financial hardship’ – it does not mean that health care is ‘free’ at the point of use. Previous Commonwealth Fund surveys have explored how upfront charges or co-payments may deter people from accessing health care when they need to.

IHP 2021 shows the NHS continues to perform well in protecting people from financial barriers to accessing health care, with those in the UK least likely to report going without the care they needed due to cost. Only 1% said they did not collect a prescription for medicine or skipped doses because of the cost – the same as France, Germany, the Netherlands, and New Zealand. The US was highest at 9%. In the UK, 2% said they had skipped a medical test or treatment because of the cost (only Sweden was significantly lower at 1%), while 4% in the UK said they did not consult a doctor because of the cost, with the US highest at 7%. There are no details given by UK respondents about what costs they might face.

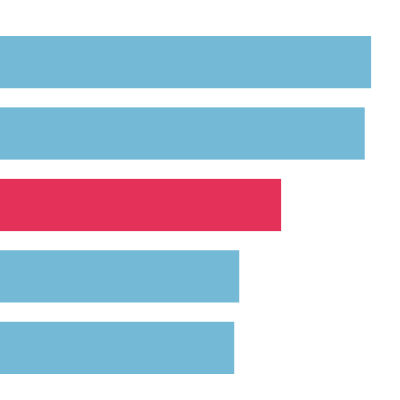

There are few upfront costs to access NHS services, especially for older adults who are exempt from charges for NHS prescriptions and eye tests. In some countries (eg New Zealand and Sweden) patients pay a fee to see a doctor, and in others (eg France) face upfront costs that are at least partially reimbursed. The survey asked people how much of their own money they or their family had spent on medical treatments or services not covered by the NHS or private insurance (for example prescriptions, dental care or co-payments for private services). The UK had highest proportion of adults reporting no out-of-pocket costs at 56%, the highest of all countries surveyed, followed by France (33%) and the Netherlands (31%) (Figure 1). At the other end of the spectrum, 34% of respondents in Switzerland reported out-of-pocket costs equivalent to over $2,000, followed by 20% of US respondents.

Figure 1:

The UK made greater use of remote appointments in primary care than many countries

High proportions of people from all 11 countries reported having a regular doctor or general practice for most of their medical care: 98% in the UK, ranging from 100% in New Zealand to 96% in the US. But the UK is different from many other countries, with people more likely to report having a regular place of care rather than a regular doctor they usually see. Of the 98% in the UK, 76% said they had one or more regular doctors or nurses they usually go to. But 22% said they had a regular practice only, with only Sweden reporting a higher proportion (30%) with only a regular practice. In the UK, the proportion of people with a regular practice rather than a regular doctor has risen over time: it was 5% in 2014 and 15% in 2017.

In 2021, compared with other countries, the UK performed relatively well in terms of people who reported being able to get an appointment quickly the ‘last time’ they were sick and needed to see a doctor or a nurse. 34% of UK respondents said they had a same day appointment, the same as the Netherlands, and exceeded only by Germany (44%) (Figure 2). It is notable that the UK’s same day proportion was also 34% in 2017, but was higher at 43% in 2014, suggesting that slightly worsening access was also a problem before the pandemic.

Figure 2:

Where the UK does stand out internationally is how some of those appointments were conducted given the pandemic. The survey suggests that the NHS made much greater use of remote appointments than many other countries. 64% of people in the UK reported having an appointment with a doctor (or other health care professional) via phone or video (Figure 2). This was only exceeded by Canada (71%). The UK, Canada and Australia are the only countries where a majority of patients reported having remote consultations. By contrast, people in other European countries reported much lower use of remote appointments, notably Switzerland (17%), France (10%) and Germany, the lowest at only 4%.

The survey asked questions about the standard of care delivered by people’s regular GP. By some measures, there has been some improvement despite the pandemic. 65% of people in the UK said their regular GP or someone at their practice ‘always or often’ coordinates or arranges the care they receive from other doctors, up from 55% in 2017. This ranks in the mid-range compared with other countries, but is significantly better than Germany (where 49% said the same), the Netherlands (49%), France (46%), Norway (46%) and Sweden (39%) (Figure 2).

People taking more than two prescription medicines were asked if a health care professional had reviewed these with them over the past 12 months, a task that in the UK normally takes place in general practice. In the UK, 58% said yes, representing a significant drop compared with 2017 (73%) and 2014 (76%). The UK was middling compared with other countries in 2021, with the US highest (87%) and Sweden lowest (42%) (Figure 2).

The UK experienced more disruption to routine care than others in Europe

The survey asked people whether they had any appointments with a doctor or other health care professional cancelled or postponed because of the pandemic, including regular check-ups and routine screening tests. Responses to this question are likely to be broader than primary care, encompassing hospital and other locations of care. 25% of UK respondents said that they had appointments either cancelled or postponed (Figure 3). This is the third highest proportion after the US (33%) and Canada (28%). Other countries ranged from 10% in Germany to 19% in France.

Figure 3:

The survey does suggest that overall contacts with parts of the NHS (such as primary care) may have dropped during the pandemic. The survey asked how many doctors people had seen in the past 12 months, excluding hospitalisations. Respondents in the UK and the Netherlands were more likely to report not seeing any doctors in past 12 months, at 28%, with other countries ranging from 5% in Australia to 16% in Canada (Figure 4). For the UK respondents, this is nearly double the rate of those who reported not having seen a doctor in 2017 and 2014 (12% and 14%), although rates of those reporting having seen one doctor were similar to 2017 and 2014 (28% in 2021 and 2014, 27% in 2017).

Figure 4:

The UK had the joint lowest number of overnight hospital admissions

The UK and Canada were lowest for reporting an admission to hospital for at least one night in past 2 years – both 20% – while Australia was highest with 32%. It is not clear whether this is a pandemic effect as people were asked to report on the past 2 years, straddling the period of the pandemic. For the UK, this is not significantly different from previous years: in 2017, 22% answered yes to this question and 18% in 2014.

There does, however, seem to have been some improvement in the care and support reported by people after a hospital stay. In the UK, 82% said they had received written information on what to do when they got home and what symptoms to watch out for. This is an improvement compared with 2017 (at 72%).

Other aspects of follow-up care after hospital discharge also compare well with other countries. For example, in the most recent survey, 82% of people in the UK reported that the hospital had arranged or made sure that there would be follow-up care with a doctor or other professional (Figure 5). This is significantly different from Sweden (46%), France (63%), the Netherlands (57%), Norway, (57%) and Germany (44%). More generally, UK respondents were among the highest proportions of those saying they felt they had the support and services to manage their condition at home after a hospital stay.

Figure 5:

Fewer UK older adults reported using A&E in the past 2 years compared with 2017

While there may have been some disruption to routine care in the UK, this was not accompanied by higher use of A&E services. Fewer people in the UK reported using A&E in past 2 years in 2021 (75% reported no visits to A&E), compared with 2017 (67%) – but similar to 2014 (74%). This ranks in the middle internationally, with Germany reporting the highest proportion of people having not used A&E (84%) and the US and Canada joint lowest (64%).

Respondents who had used A&E were asked if it was for a condition that they thought could have been treated by doctors or staff ‘at the place where you usually get medical care’, had that been available. In the UK, 16% said yes, similar to Germany (15%), while five countries had significantly higher rates, including Australia, (26%), Switzerland and the US (27%), Canada (30%) and the Netherlands (33%). The UK’s 2021 rate was significantly lower in 2017 (25%).

People in the UK needing help at home have a higher reliance on informal social care

The survey asked older adults about their general health and whether they had any limitations in day-to-day activities, such as dressing and bathing.

46% of UK older adults described their health as ‘excellent’ or ‘very good’, a proportion that has increased slightly compared with previous years (43% in 2017, which was not significant, but better than 39% in 2014). Internationally this figure ranged from 22% in France to 60% in New Zealand. The survey also asked about the degree to which people felt limited in their ability to do everyday activities. In the UK, 15% said their everyday activities were severely or somewhat limited, lower than France (18%), Germany (29%) and Switzerland (25%) with other countries reporting similar rates to the UK.

The same proportion (15%) in the UK said they needed help at home with shopping, housework or preparing meals, in the middle internationally. The highest proportion saying they needed help were in the Netherlands (22%) and Australia (19%), with Sweden the lowest at 8%.

This smaller subset of people were asked about what sort of help, if any, they received. Of these, 79% in the UK reported that they always or often got help with activities at home. This is significantly higher than Canada (59%), France (65%), Germany (60%), the Netherlands (64%), Norway (45%) and the US (59%).

Compared with other countries, the UK had low proportions of people reporting paid or professional help in the home: 28% in UK said they had paid help (Figure 6), compared with Norway (62%), Sweden (43%) and Germany (42%). UK respondents were also more likely to report having help from a family member or friend: 82% said they had help from family or friends, significantly higher than France (53%), the Netherlands (55%), and New Zealand (61%).

Figure 6:

The survey asked people whether their care at home had been disrupted because of COVID-19. In the UK, 30% said they did not get the help they needed because services were cancelled or very limited due to the disruption. This was the second highest after Canada (31%). Oher countries ranged from 8% in Germany to 23% in US.

Disrupted services were a much more common reason for missing help than fear of contracting the virus. In common with most European countries, the proportion of people reporting they did not have help because they did not want anyone in the home because of COVID-19 was modest. 10% of UK respondents said they did not get care as they were concerned about someone in home due to COVID-19. The outliers were New Zealand (at 1%) and Canada, at the other end of the spectrum, at 18%.

What the findings tell us

Disruption to essential health and care services has been reported in all regions of the world as a result of the pandemic, which is continuing to affect primary and community care, and elective surgery in particular. For the NHS in England, evidence has grown steadily of the depth and enduring nature of delays and disruption to a broad range of services, including general practice, routine hospital care, and health and social care in the community.

What has been less clear is how severely the UK health and care system was hit compared with other countries. The survey helps shed some light on this from the perspective of older people, many of whom are more reliant on health and care services than younger populations.

Primary care

Studies from the US and Europe suggest that primary care services experienced a fall in activity and increased use of remote consultations in 2020. The snapshot provided by this survey, some months later in 2021, suggests that primary care in the UK had mixed fortunes compared with other countries, and in some respects has performed relatively well. For example, the survey suggests that access to same day GP appointments in the UK is no worse than in 2017 and is better than most of the other countries. People in the UK reported greater coordination of care by general practice than in previous surveys, although reviews of medication may have suffered. Research from the first year of the pandemic found that some general practices were able to prioritise care for those who needed it most, particularly for older age groups and those with pre-existing conditions. This survey does not suggest that there were any spill-over effects for the use of A&E, for conditions that people thought could be treated where they normally receive care.

In other respects, the restrictions placed on access to care to protect patients and staff may have accelerated some pre-existing trends. For example, the proportion of people reporting having a regular practice only, rather than seeing a regular doctor or nurse, has risen over time. This suggests that a reduction in continuity of care accelerated during the pandemic. The most recent GP patient survey in England recorded a decline among those (of all age groups older than 16) saying they could see their preferred GP ‘always or almost always/a lot of the time’ from 50% in 2018 to 45% in 2021 (although there was no change between 2020 and 2021).

Although there has been controversy in England surrounding the appropriate balance of remote versus face-to-face appointments in general practice, the survey shows that the UK was among the most adaptable in changing the mode of consultations. This may be partly a function of the UK’s national health service allowing for rapid local change within national guidelines, and not hampered by inflexible payment systems, as seems to have been the case in the US for example.

Hospital care

The first wave of the pandemic brought severe disruption to elective surgery across the world. A study of the hospital sectors in France, Germany, and the Netherlands showed that all reported reduced activity and reprioritisation of treatments, and were expecting a lower rate of hospital activity for the foreseeable future. On the evidence of this survey, respondents in the UK had appointments or treatments cancelled at a higher rate than other European countries, but not as high as the US and Canada. The increase in the proportion of people in the UK saying they did not see a doctor of any kind in the past 12 months may also reflect a drop in hospital outpatient attendances. But the proportion seeing two or more held steady, suggesting that those who needed more clinical input may have been prioritised.

Respondents in the UK were among the lowest compared with other countries to report an overnight hospital stay, but the proportion is in line with previous years. This may be less a pandemic effect, and more a wider reflection of the varying intensity of medical care internationally, with the NHS on the leaner end of the spectrum in terms of beds and doctors per capita. Where a person did report an overnight hospital stay, the UK’s performance in ensuring support and coordination after discharge was good, both compared with other countries and previous years. This may reflect the additional focus (and resources) to improve temporary support for people after discharge from hospital during the pandemic, which was accelerated in order to free up hospital beds. The additional emergency funding for discharge support has now ended.

Overall, there is increasing concern about how quickly the NHS can recover from the pandemic given the UK’s limited health system capacity – particularly staff and equipment – compared with other countries. In England, the speed with which the NHS can reduce increasingly long waiting times is uncertain. This is because it remains unclear how many ‘missing’ patients, who did not (or could not) access care during the pandemic, will reappear. Adding to the pressures, there are also longstanding staff shortages (over 110,000 by December 2021), the impact of rising inflation on NHS budgets and staff pay, and continuing disruption from COVID-19 on the delivery of services.

Social care in the home

Finally, it stands out that UK respondents had a lower likelihood of receiving paid-for care compared with other countries, combined with a higher likelihood of reliance on informal social care in the home, particularly from family and friends. The number of people responding to the questions on care needs was small (a subset of 368 people). But the results are consistent with the current social care system, where access to publicly funded care in the home is restricted, subject to a needs test in Scotland, and in England and Wales by a financial means test as well.

The UK already had a high reliance on informal carers compared with other countries, and this reliance grew during the pandemic as services were disrupted, increasing the number of unpaid carers by an estimated 4.5 million. Pre-pandemic workforce shortages in home-care providers worsened as a result of COVID-19, which doubled the rate of staff sickness in 2020/21. The survey’s finding that a third of people did not get the help they needed at times because services were cancelled or restricted reflects the severe impact of COVID-19 on social care services. In England, the government’s policies to protect social care users and staff in the early stages of the pandemic have been heavily criticised. Plans for social care reform and additional funding announced in 2021 for England will not address unmet need for care, improve pay and conditions for social care staff nor bring higher quality services.

Conclusion

The survey confirms that the UK was far from alone in experiencing widespread disruption to essential health and care services for older adults. Some aspects of care have held up well, such as speed of access to general practice and support after a hospital discharge. But the UK’s higher rates of cancelled or missed appointments compared with other countries signal the challenges that lie ahead for the NHS, as it attempts to recover with a much leaner and under-resourced health and care system relative to other comparable countries.

The Commonwealth Fund provided core funding, with co-funding or technical assistance from the following organisations:

-

Canada: Ontario Health; Canadian Institute for Health Information; Commissaire à la santé et au bien-être du Quebec; Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux.

-

France: La Haute Autorité de Santé; Caisse Nationale d'Assurance Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés; Directorate for Research, Evaluation, Studies, and Statistics of the French Ministry of Health.

-

Germany: German Ministry of Health and BQS Institute for Quality and Patient Safety.

-

Netherlands: Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport and Radboud University Medical Center.

-

Sweden: Swedish Agency for Health and Care Services Analysis (Vård- och omsorgsanalys).

-

Switzerland: Swiss Federal Office of Public Health.

-

UK: The Health Foundation.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more