Longer waits, missing patients and catching up How is elective care in England coping with the continuing impact of COVID-19?

13 April 2021

Key points

This analysis looks at what we know about the impact of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on elective care in England.

- While the NHS delivered a remarkable amount of elective treatment during the second wave of the pandemic, the pressure of caring for large numbers of patients seriously unwell with COVID-19 has led to longer delays for the growing number of patients on the waiting list.

- Data on clinical pathways show that four million fewer people completed elective treatment in 2020 compared with 2019 (down from 16 million to 12 million).

- The rapid expansion of remote consultations helped limit the disruption caused by the pandemic, but patients who need to be admitted to hospital for treatment are tending to wait longer than those who can be diagnosed and treated remotely.

- Services in every part of England were placed under enormous strain during the pandemic, but the varying impact those pressures had on routine hospital services broadly reflects regional differences in COVID-19 infection rates and hospitalisations.

- Just as COVID-19 has exacerbated existing inequalities in other parts of life, access to elective treatment fell further in the most deprived areas of England during 2020 than in less deprived areas.

- As well as fewer patients being treated, 2020 saw six million fewer people referred into consultant-led elective care than in 2019. These 'missing patients' remain the biggest unknown in planning to address the backlog of unmet need created by the pandemic.

- The waiting list has now reached the highest level since comparable records began, with more patients experiencing long delays in diagnosis and treatment. The waiting list could still grow substantially depending on how and when the 'missing patients' are belatedly added.

Introduction

Last year, we looked at the stark impact of the pandemic on elective care in England. The initial outbreak of the virus forced the NHS to postpone enormous volumes of activity to free up staff and beds for patients seriously unwell with COVID-19, which had consequences for millions of people.

Thanks to the hard work of NHS staff, considerable progress was made in restarting routine hospital services before winter – albeit not yet to pre-pandemic levels, let alone the extra activity needed to address the backlog created by the pandemic.

However, the NHS was placed under extreme strain during the second wave of the virus. From 2 November 2020 to 3 March 2021, there were never fewer than 10,000 patients in hospital with COVID-19 – with a peak of 34,336 on 18 January 2021, almost double that of the initial wave. In the first 3 weeks of the new year, more than 3,000 new patients with COVID-19 were admitted to hospital every single day.

What consequences did this have for the growing backlog of patients needing routine hospital services? How big of a setback has the NHS experienced in recent months? And was the impact the same across different clinical specialties or particular parts of England?

Here we present six charts looking at the impact of the pandemic on consultant-led elective care, using referral to treatment waiting time data published by NHS England.

A patient referred into consultant-led elective care begins a new treatment pathway that is usually completed when definitive treatment starts, when the patient declines treatment or when there is a clinical decision that treatment is not needed. The suspension of routine hospital services caused a sharp drop in the total number of treatment pathways being completed in April and May 2020. While the NHS made substantial progress towards restarting the suspended services, only 12 million treatment pathways were completed during 2020 – compared with 16 million completed during 2019.

Routine hospital activity fell again in December 2020 and January 2021, albeit by far less than might have been feared. This was a major achievement, in the context of a severe second wave and the sheer number of patients in hospital with COVID-19. But it still represents a setback for the growing number of patients still waiting for treatment, as hopes fade that the backlog can be addressed quickly. It also underlines how keeping the virus under control will remain an important factor in how quickly elective care can return to full capacity.

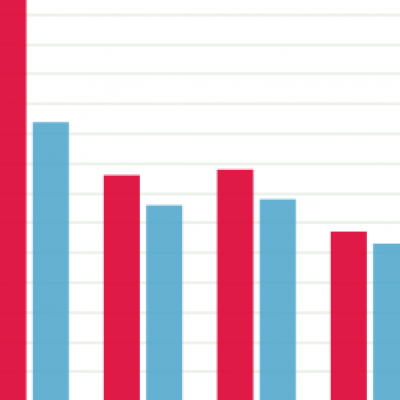

During 2020, treatment activity fell further in some specialties than in others, potentially leading to bigger delays for patients waiting for certain procedures (such as hip replacements and oral surgery). All clinical specialties were disrupted, but the rapid expansion of remote consultations appears to have helped limit the impact in specialties where a higher proportion of treatment pathways are completed in an outpatient service. This includes dermatology, thoracic medicine and neurology, where activity was respectively 20%, 20% and 19% below 2019 levels.

The largest impact on treatment activity was in trauma and orthopaedics, oral surgery and ear, nose and throat (ENT), with respective falls of 38%, 37% and 37% compared with 2019. In these specialties, a greater proportion of pathways end in inpatient or day case settings (so there is less scope to complete treatment pathways via remote consultations).

December and January again saw activity fall further in these specialties, albeit not to the extent seen in the first wave. Lower levels of activity mean longer waits – by January 2021, 32% (114,407) of ENT patients had waited more than 6 months, compared with 14% (27,254) of dermatology patients.

The NHS came into the pandemic with less hospital capacity than most comparable countries – so every national or local surge in COVID-19 cases and hospitalisations had consequences for elective care. However, there were regional differences in the extent of the slowdown in completed treatment pathways and the speed of progress in restoring services.

All regions experienced significant reductions in elective activity, but the largest fall was in the North West, with 31% fewer total completed pathways in 2020 than in 2019. The smallest reduction was in the South West, which still recorded a 24% reduction compared with 2019. The South West, along with the East of England, came closest to restoring services to pre-pandemic levels prior to the second wave. That both regions generally had below average rates of the virus is unlikely to be coincidence.

It’s also worth noting that specialised services for rare and complex conditions – which are nationally and regionally commissioned (by NHS England) but provided in centres across England – fell by 33%.

The evidence is increasingly clear that people’s experiences of the pandemic have been shaped by pre-existing inequalities, and elective care has been no different. To analyse the varying impact, we grouped all NHS Clinical Commissioning Groups into quintiles based on Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) scores – which ranks every part of England from most to least deprived.

We found that between 2019 and 2020, the number of completed treatment pathways fell by 9,162 per 100,000 population in the most deprived areas of England, compared with a fall of 6,765 in the least deprived areas. A similar picture was found for cancer referrals. And poverty is not the only factor to consider – new analysis of patient-level data found a larger fall in elective activity for people resident in care homes than for the wider population.

While the pandemic continues to affect every patient needing routine hospital services, the emerging evidence shows that some have been (and will be) far more affected than others.

Meeting the needs of those already waiting for diagnosis and treatment will be tough, but at least these patients are on the radar – a considerable number of others are currently not. GP services were open throughout the pandemic but, with people reluctant to use health services and hospitals able to accept only to the most urgent referrals, there was a sharp fall in the number of people starting new treatment pathways.

Substantial progress was made in recovering the number of new pathways over the year. And the number of new pathways started in December and January was less affected by the second wave than might have been expected – though there was still an impact. However, even with this progress, only 14 million pathways were started last year – meaning 6 million (29%) fewer people sought treatment in 2020 than in 2019.

As the health concerns that would otherwise have prompted people to seek treatment (and hence be referred to elective care) are unlikely to have simply disappeared, these 6 million people can be thought of as ‘missing patients’. Whether, when and how these missing patients will be added to the actual waiting list remains the single biggest unknown in planning to address the elective care backlog.

The slowdown in elective care due to the COVID-19 pandemic has been a major shock for how long patients are waiting for treatment. The NHS was already struggling to achieve the 18-week standard for several years prior to the pandemic, but by January 2021 the number of patients who had waited longer than 6 months exceeded 1 million, with around 304,000 people waiting over a year for treatment.

The waiting list is now at the highest level since comparable records began (in 2007), currently at 4.6 million. While this figure is not substantially higher than the 4.4 million waiting prior to the pandemic, it must be seen in the context of the millions of missing patients highlighted above. Projections by the REAL Centre suggest that if 75% of those patients are belatedly referred into specialist care, the waiting list could reach 9.7 million by March 2024, with fewer than half of patients treated within 18 weeks.

Conclusion

The NHS was already struggling to keep pace with the growing demand for elective care prior to the pandemic, largely due to staff shortages and limited hospital capacity. COVID-19 has made the situation considerably more difficult.

The notion that COVID-19 was ‘the great leveller’ has been comprehensively shattered by the evidence – with people in the most deprived parts of England twice as likely to die from the virus as those in the least deprived areas. Similarly, patients in the most deprived parts of England experienced poorer access to elective care during the pandemic than those in less deprived areas.

Each specialty and each region of England will start the recovery from a different position. The continuing need for social distancing and enhanced infection prevention and control measures means more capacity will be needed just to treat the same number of patients as before the pandemic. There will have to be difficult decisions made about which patients to prioritise. Care must be taken to ensure the process of recovery does not further exacerbate existing inequalities.

The NHS has been severely tested by COVID-19 and, even before the second wave, the workforce was stressed and exhausted. The same staff who went above and beyond to care for patients seriously unwell with COVID-19 now face the daunting task of addressing the backlog. NHS leaders have already warned that pushing too hard, too soon to start the elective recovery could backfire by leading staff to leave the service, worsening staff shortages. Praise for the NHS must translate into practical support and significant investment in the next Spending Review.

Restoring elective care to pre-pandemic levels and addressing the growing backlog of patients is likely to take years, rather than months. Doing so equitably – and without sacrificing the broader ambitions to modernise care in the NHS Long Term Plan – is likely to be one of the defining challenges between now and the next general election, and almost certainly beyond.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more