Better housing is crucial for our health and the COVID-19 recovery

Better housing is crucial for our health and the COVID-19 recovery

28 December 2020

Key points

- Going into the COVID-19 pandemic, one in three households (32% or 7.6 million) in England had at least one major housing problem relating to overcrowding, affordability or poor-quality housing.

- Housing problems like these can affect health outcomes – including physical health directly from poor quality homes, and mental health from affordability or insecure housing.

- 1 million households in England experience more than one housing problem. Having multiple housing problems is associated with even worse health.

- While fewer homes are classed as non-decent compared with 10 years ago, overcrowding and affordability problems have increased in recent years.

- The pandemic has highlighted the health implications of housing. Poor housing conditions such as overcrowding and high density are associated with greater spread of COVID-19, and people have had to spend more time in homes that are overcrowded, damp or unsafe. The economic fallout from the pandemic may lead to an increase in evictions.

- These housing problems have multiple causes: a focus on increasing supply to the detriment of other objectives; sustained reductions in housing benefits; and a private rented model which does not meet the needs of tenants.

- A combination of greater investment in social housing, more secure private tenancies, and reversing reductions in housing benefit support – such as the cuts to Local Housing Allowance (LHA) – will be needed to improve the contribution of housing to health.

To explore our full analysis of how housing affects health, visit our What drives health inequalities? evidence hub.

Figure 2 looks at the number of non-decent homes in England by housing tenure over time. In 2006, 35% of homes (7.7 million) were classed as non-decent. In 2019, this had fallen to 17% of homes (4.1 million), meaning that 2019 saw the lowest percentage of non-decent homes since records began.

Figure 2

This reduction of 3.4 million fewer non-decent homes has been driven by different factors. In the social rental sector, standards improved mainly thanks to the Decent Homes Programme of investment, which began in 2000. Improvements in privately owned homes may reflect spending by households or landlords, and shifts between tenures. For example, the Right to Buy scheme has seen social homes, typically the better-quality ones, continue to move into owner-occupation. Tighter regulation – such as recent changes to building regulations compelling landlords to improve electrical safety – also prompted improvements in the quality of some housing.

Looking at the proportion of homes in each tenure that are non-decent, the private rented sector has the poorest quality housing, with 25% of homes considered non-decent. For social rent, 15% of homes are considered non-decent. Even though the private rented sector is the worst individual tenure, the sheer number of owner occupiers (as seen in Figure 1) means that tackling non-decent homes overall requires policy solutions for owner-occupied homes too.

Improving non-decent homes might be easiest in social housing, where there are relatively few landlords, the landlords tend to be responsible for many properties and there is more state oversight. In contrast, the UK private rental sector is dominated by ‘cottage industry’ landlords, with 52% of rental properties owned by landlords with fewer than five properties.

Overcrowding – defined as when the number of occupants of a home exceed the space they could reasonably be expected to inhabit – is another measure of housing condition and is often associated with affordability. As in Figure 3, overcrowding in England has become a more widespread problem in recent years, with large increases in overcrowding in rented tenures.

Figure 3

Figure 4 shows the association (adjusted for age) between psychological distress as measured by GHQ-12 and overcrowding. Distress is generally higher for overcrowded households, and data from the pandemic period seem to show this intensifying during the more severe lockdown in April 2020, when 39% of people in overcrowded households were indicating psychological distress. Conversely, adults living alone are more likely to report loneliness.

Figure 4

Stability and security of housing

Feeling secure in your home is another aspect of housing that is important for health and wellbeing – it can provide a sense of continuity and stability for other areas of life. While difficult to measure directly, home moves and duration of tenure can be used as proxies for general security. Of course, people can move for many reasons, including positive ones (such as moving to better accommodation), but frequent relocations can also indicate insecurity.

Since the 1990s, there has been little change in the probability that social renters or owner occupiers will move in a given year. In the private rented sector, moves are less common today (with around 25% occupiers moving each year) than they were between the mid-2000s (around 40% moving per year). However, the private sector overall has grown: there are more families with children renting now (1.7 million families renting in 2020 compared with 0.8m in 2010), and this group may value stability more highly. While moving is less frequent in the private rented sector than before, but is still high compared to other tenures.

Figures 5 and 6 use the Millennium Cohort Study (which follows a group of children born in 2000) to show the relationship between health, the frequency of home moves and housing tenure.

Figure 5 shows that households with children in owner-occupation are less likely to have experienced multiple moves, and those living in the private rented sector are most likely to. Social housing offers more stability than the private rented sector.

Figure 5

Figure 6 shows the link between moving homes and health for the parents in this study. By the time the children were 15, there was a clear association between those who moved the most and parents with the worst self-rated health, with statistically significant differences between each category (except between one and two moves). The same data also show an association between moves and poverty status. The data do not show that moves cause poor health, or vice versa – simply that there is an association between the two.

Figure 6

Academic work has also explored these associations. There are well-established links between residential mobility and child mental health, educational outcomes and emergency hospital admissions. As in Figure 6, residential mobility among adults is also associated with poorer health behaviours and outcomes. If housing insecurity increases as a result of the pandemic, this may lead to an increase in residential moves. Private renters are more likely to be hit by the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic and may be at risk of eviction once protections expire.

There has also been a rise in the number of people in temporary accommodation, rough sleeping and acceptance of homeless status following the end of assured short-hold tenancies. These more severe forms of homelessness are strongly associated with worse health outcomes.

Housing affordability

Housing affordability can affect people’s mental health directly, as well as reducing the resources available to them to spend on other goods and services. Struggling to meet housing costs can lead to rent or mortgage arrears, which can lead to eviction or repossession.

However, affordability can be difficult to measure. If someone spends a high proportion of their income on housing costs, this could be a discretionary choice to gain better housing, but equally it could represent an involuntary burden. Nonetheless, in the UK there is some evidence of a link between problems paying for housing and the ratio between housing cost and income.

Figure 7 shows big differences in the proportion of households spending more than a third of their (net) income on housing by tenure. This reflects both the cost of housing but also differences in incomes between tenures (it does not include those owner-occupiers who own their homes outright). Social housing tends to be cheaper than other forms but is also allocated to those in disadvantaged circumstances, which is why 10% of social renters still spend more than a third of their income on housing.

Figure 7

Policy decisions have begun to erode affordability in social housing – for example, the 'bedroom tax' and the benefit cap, both put in place in 2013. The bedroom tax reduced housing benefit for those who under-occupy their home, while the benefit cap reduced housing benefit for those whose total benefit income exceeds a certain level. An increase in housing cost burden is clearly visible from the early 2010s onwards in the social rented sector.

Compounded by the limited supply of social housing, policy decisions have also eroded private sector affordability. There has been a partial reversal through the COVID-19 response, but the level of support for private rents was decoupled from private rental costs in 2011, and then frozen altogether between 2016 and 2020. This has meant that government support only fully covers a lower proportion of properties in any given area, thereby exacerbating further problems such as homelessness.

Problems with affordability are not evenly distributed across the UK. 21% of people in London are in households with a housing cost burden, based on the definition of spending more than a third of their (net) income on housing. This is considerably higher percentage than in the next worst region (which is South East England, at 12%).

What happens to health when households experience multiple housing problems concurrently?

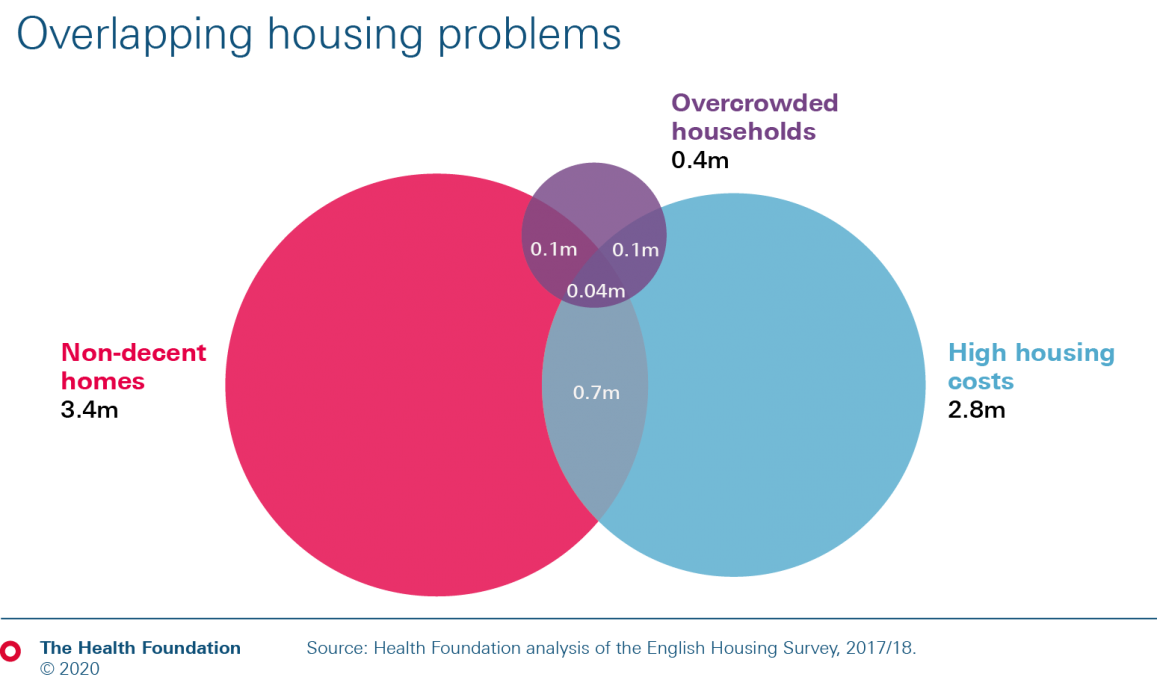

Problems with housing conditions, security and affordability can be experienced in parallel, which has big implications for health and for policymaking. Figure 8 looks at two of these factors (affordability and quality of the home), as well as overcrowding. Ideally this analysis would also cover housing insecurity, but this is harder to capture in one variable, so affordability provides a proxy measure. Overall, 7.5 million households in England in 2016/17 (32% of all households) experienced either overcrowding, an affordability problem, or lived in a non-decent home. 1 million households experienced more than one housing problem, with around 700,000 of those experiencing high housing costs relative to income while living in a non-decent home. A relatively high proportion of households facing overcrowding also face one or more other problems.

Figure 8

Figure 9 looks at these overlapping problems in the context of the self-rated health of the head of household. More than one in three of the 1 million households with multiple housing problems are headed by an individual rating their health as less than good, compared to one in five for households with no housing problems. 11% of those with one or more housing problems self-rated their health as poor or very poor, almost double the figure for those with no major housing problems. These differences are statistically significant. This matters for policy solutions, as indicated by Australian research which argues that separating out different aspects of housing can underestimate their association with health.

Figure 9

Figure 10 looks at these housing problems by tenure type. The type of tenure can shape the nature of the policy response required because of the differences in owners, structures and required incentives. Improving the standard of social housing means councils or housing associations investing in their large holdings of properties, or being funded by central government to do so, as with the Decent Homes Programme.

Figure 10

In contrast, improving the quality of homes for owner-occupiers means persuading millions of individual homeowners to do so – an intervention that might be more suited to tax reliefs or grants than overseeing direct spending to all these households (especially to help avoid ‘deadweight’ loss, when an occupier would invest in their own property anyway). The Centre for Ageing Better investigated this problem and recommended new funding mechanisms and financial products to support owners to bring their homes up to standard. Those with all three housing problems are largely in the private rented sector, although this is a small group of households with a correspondingly low sample size in the survey, meaning extensive conclusions cannot be drawn from this.

Different housing problems affect different groups in ways that matter for policy, as clearly shown in Figure 10. To address non-decent housing, policy needs to include the owner-occupiers who make up this group. On the other hand, tackling issues of overcrowding and affordability requires a focus on the rental sector. The next section looks at housing policy in recent years in England, before considering the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on housing.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more