Health and social care funding

Priorities for the new government

Health and social care funding

23 November 2019

Key points

This long read was produced during the 2019 General Election.

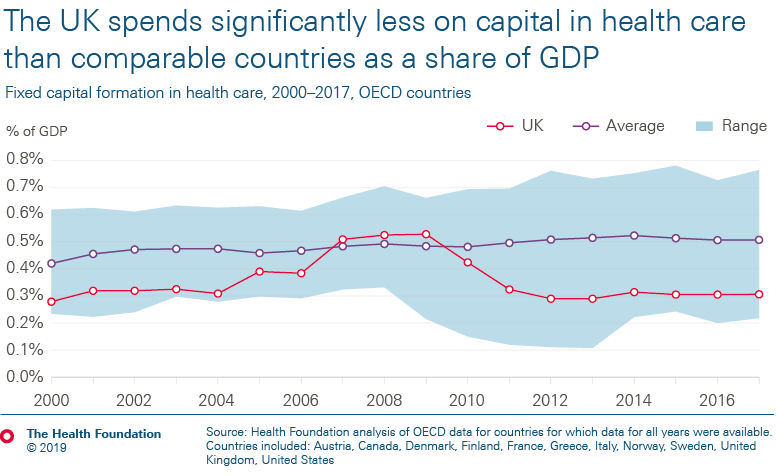

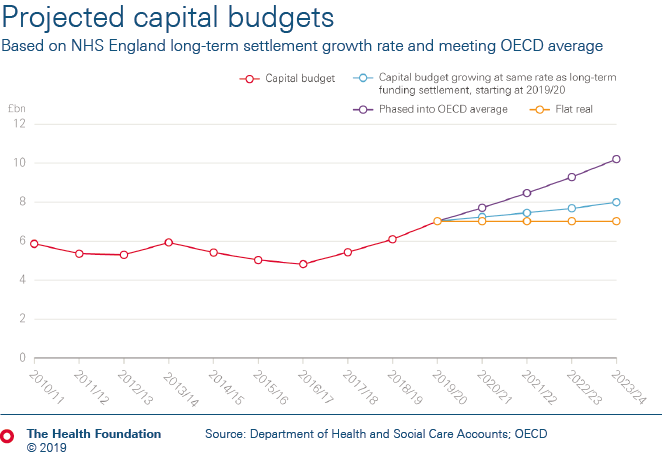

- UK health spending has grown by 1.6% a year over the last 4 years. This is much less than half the historical average growth rate. Compared to similar countries, the UK’s day-to-day spending on health is around average, but capital investment is notably low.

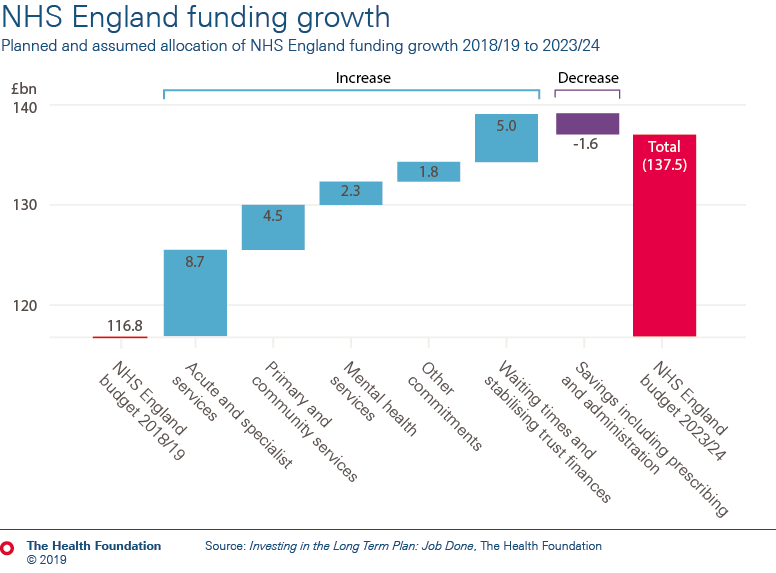

- In England, the strategy for the NHS – the NHS long term plan – is underpinned by a funding settlement up to 2023/24, with average annual increases of 3.3% a year, starting this year. But this is against a backdrop of significant hospital deficits, a maintenance backlog and workforce shortages – all flowing from previous inadequate investment.

- The funding settlement doesn’t cover the full budget for the NHS in England. Budgets for workforce education and training, public health and capital continue to have neither a plan nor long-term funding. Without further investment in these areas, quality and access to care are at risk of deteriorating further. As things stand, the total health budget will increase by just 2.9% a year to 2023/24.

- Maintaining current standards of care will require funding for these areas to increase by at least 3.4% a year – £3bn of funding in 2023/24 above current announcements. Investing in and modernising the health service as set out in the NHS long term plan requires around 4.1% a year – a further £4bn above that figure.

- The focus on mental health, primary and community services in the NHS long term plan is welcome. But there remain real challenges to ensure that this is not undermined by staff shortages, which despite the extra funding will prevent the intended improvements to these services.

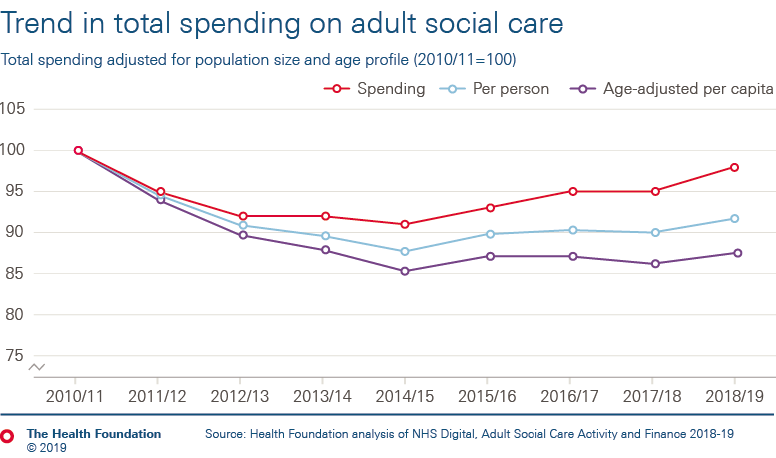

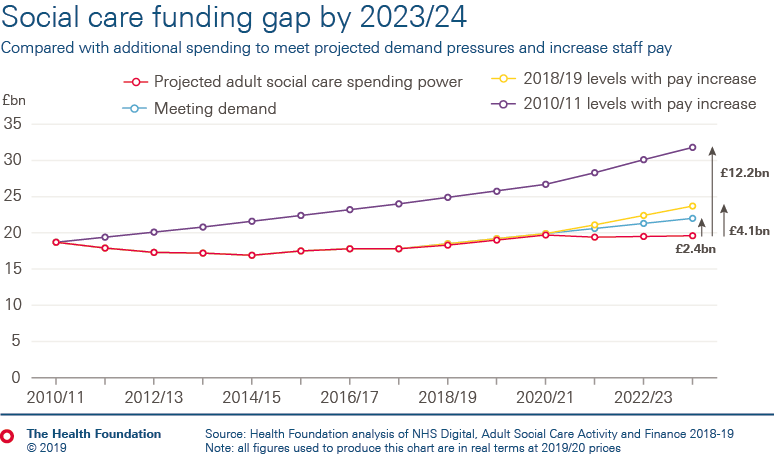

- The greatest challenge lies in adult social care. Increasing numbers of people are unable to access social care, and care providers are at risk of collapse. Funding has not kept pace with demand, falling in real terms for most of this decade. Restoring access to 2010/11 levels of service, and investing to stabilise the social care workforce, would require an increase of £12.2bn compared to estimates of funding available in 2023/24 for councils to spend on social care.

- Read our latest estimates of the funding needed to stabilise the adult social care system in England.

Note: In this long read, all amounts are expressed in 2019/20 prices using the GDP deflators at market prices, and money GDP September 2019 from HM Treasury, unless otherwise stated.

From 2019/20 onwards, additional funding exists in NHS England and Department of Health and Social Care budgets. This is to compensate for higher-than-expected employer contributions relating to public service pension schemes. When we refer to these budgets in this long read, we remove the impact of these pension changes to ensure a consistent timeseries – except where specified, such as Table 4.

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more