Key points

This long read was produced during the 2019 General Election.

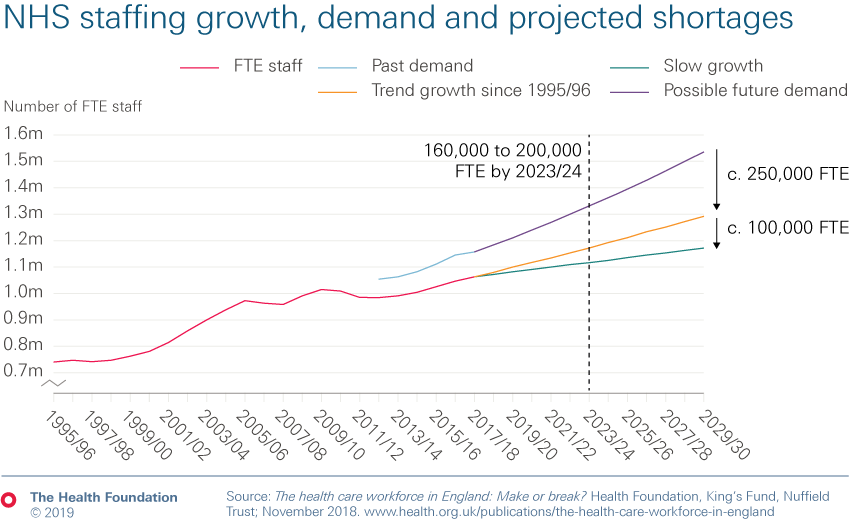

- The number of people employed by NHS providers in England this decade has grown at just half the rate of the 2000s, despite growing need. As a result, the NHS reports a workforce shortage of around 100,000 staff.

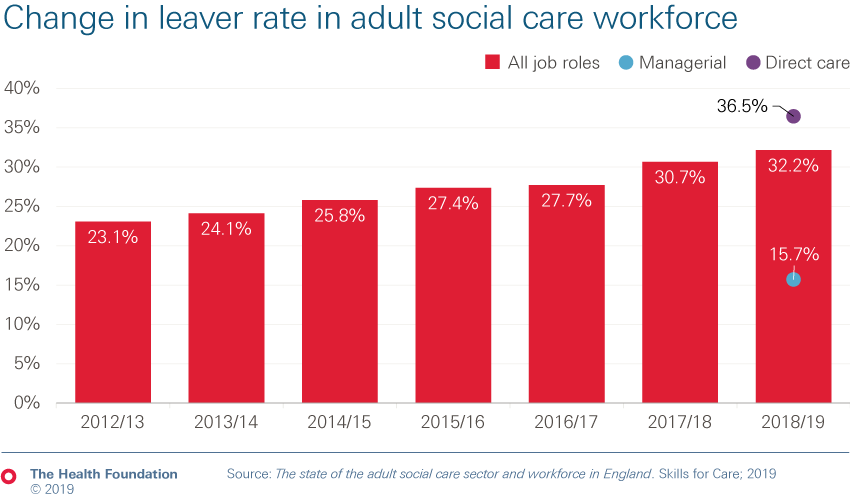

- The issues in social care are even greater and the outlook is concerning. Workforce shortages stand at around 122,000, with a quarter of staff on a zero-hours contract.

- Our projections, with the King’s Fund and the Nuffield Trust, suggest that without concerted policy action and dedicated investment, NHS shortages could grow to up to 200,000 by 2023/24, and at least 250,000 by 2030. Nursing remains the key area of shortage (of over 40,000) – and this could double by 2023/24 and grow to over 100,000 by 2028/29.

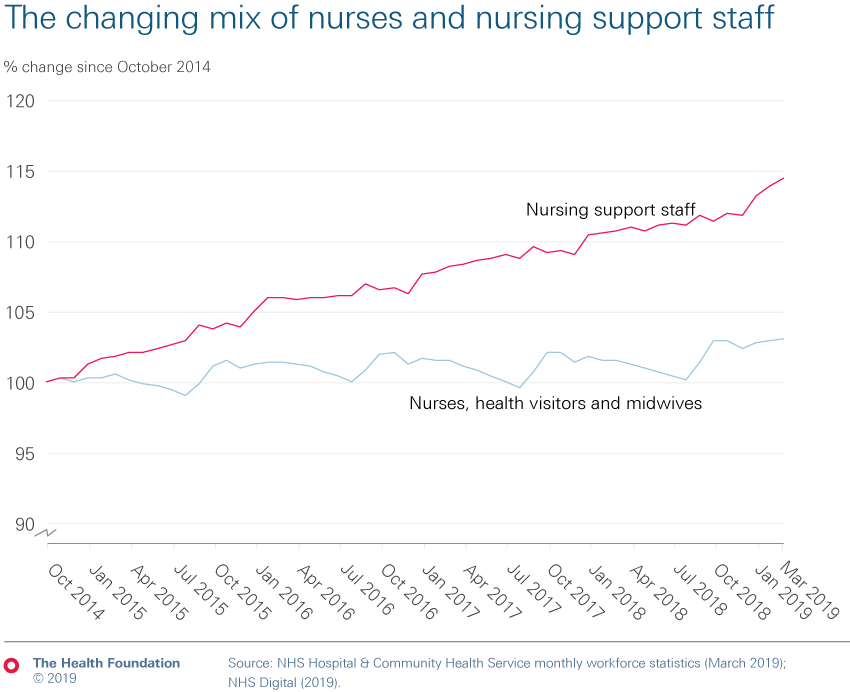

- The number of nurses has grown at just one-third the rate of both doctors and clinical support staff in the past 5 years. Within nursing, the number of nurses working in community and mental health services in 2019 remains below 2014 levels.

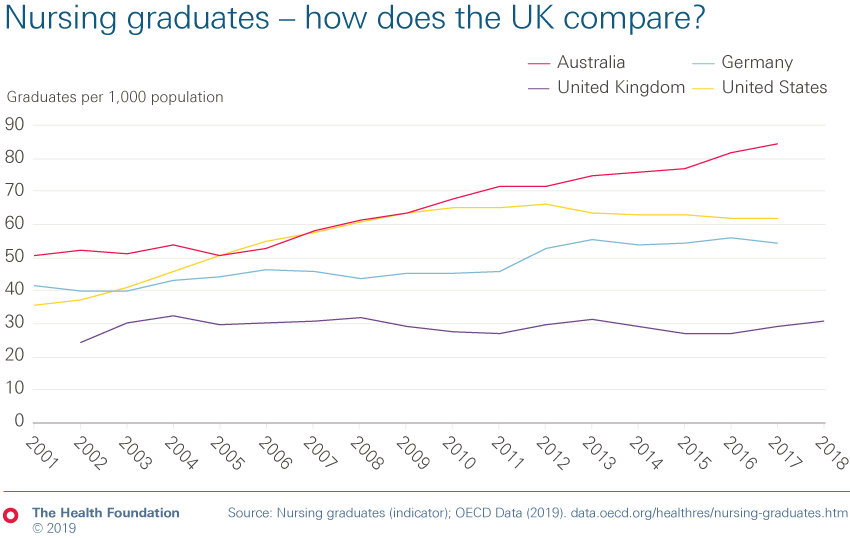

- This is partly caused by a failure to train enough nurses. In 2011 the number of training places was reduced by more than 10%. The removal of the nurse bursary in 2017 was designed to allow higher education to expand places but it has had limited impact on the number of students in training. Numbers are far below the 25% expansion planned, one in four nurses don’t complete their studies in the expected time and there are fewer mature students training in areas of mental health and learning disability.

- Cost of living is a significant barrier for many. Nursing students tend to be older, have more financial commitments, and NHS training precludes undertaking other part-time work. We have recommended offering ‘cost-of-living grants’ of around £5,200 a year to help this.

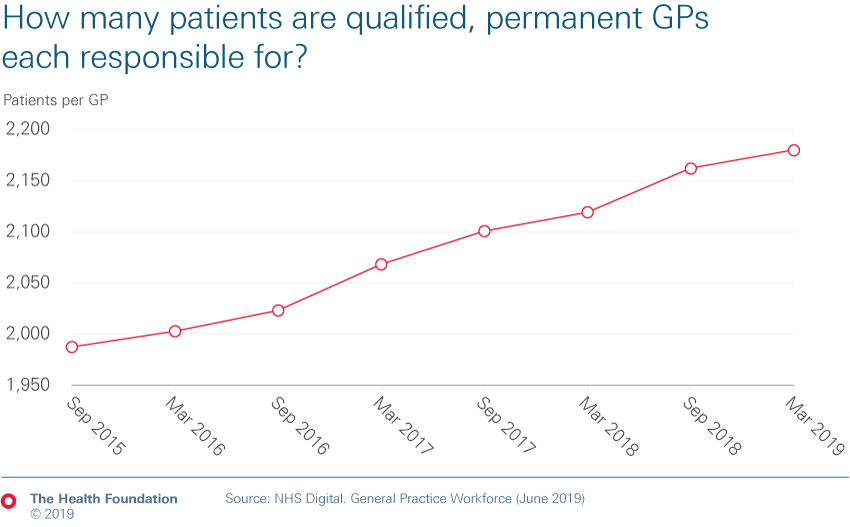

- Despite a 2015 target for 5,000 additional GPs by 2020, the number of qualified permanent GPs has fallen. As a result, the number of patients per GP continues to grow, from 2,120 to 2,180 last year alone.

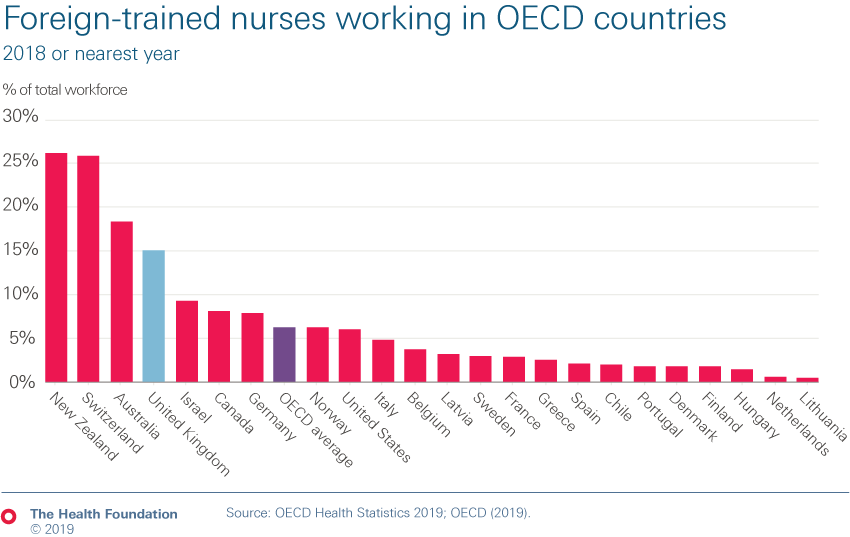

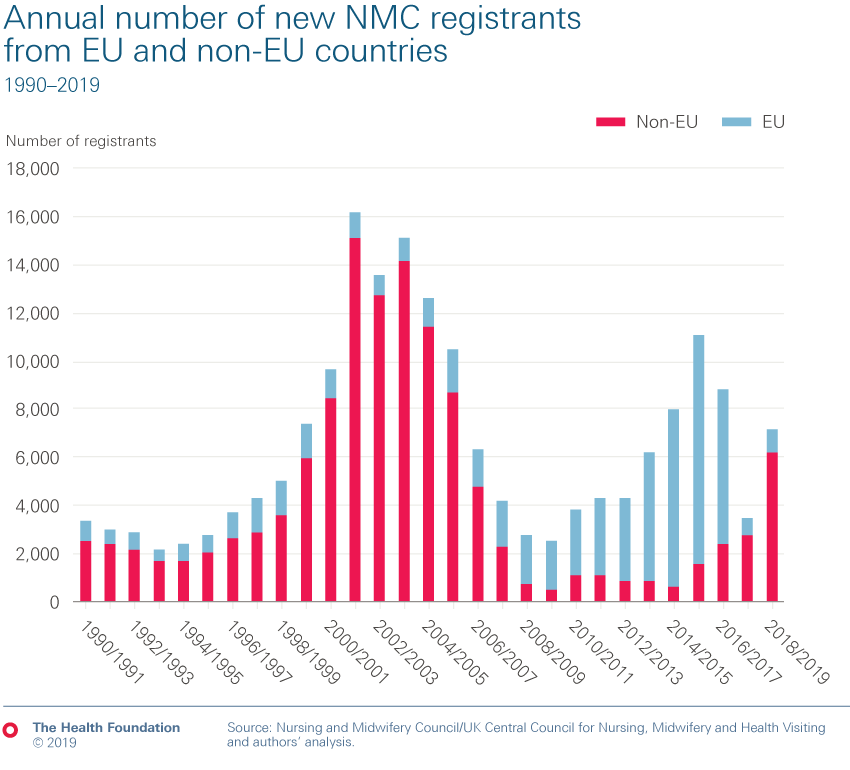

- One consequence of the failure to train and retain staff is that the UK is heavily reliant on international recruitment. This needs to continue: at least 5,000 nurses sourced from abroad a year need to be recruited until 2023/24 to reduce shortages. In 2017/18, the latest data available, just 1,600 nurses from overseas joined English NHS trusts. We do know how many overseas nurses are registered in the UK and therefore potentially available to work in the NHS. There are 33,000 EEA nurses on the register. In 2018/19, 3,400 more nurses came to the UK from outside the EU than in 2017/18. This follows an 85% fall in the number coming to the UK from the EU in recent years.

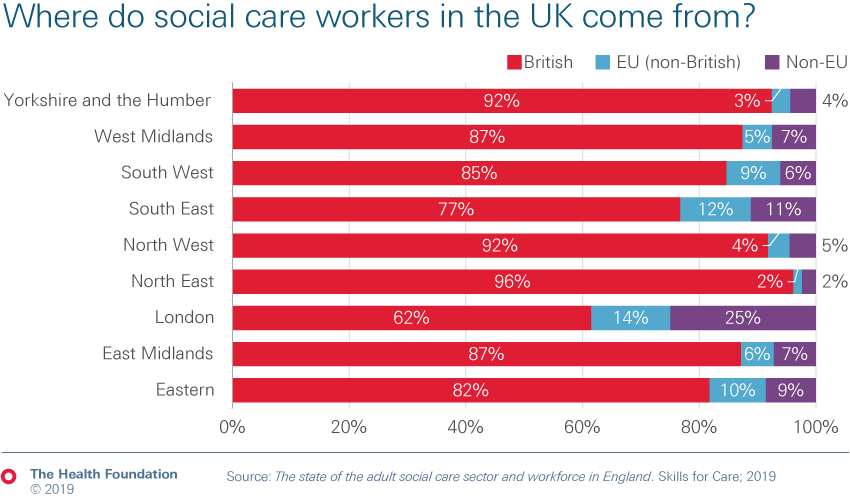

- The social care sector employs a quarter of a million people from beyond the UK. Some areas of the country are particularly reliant; 40% of social care staff in London are from overseas. International recruitment is vitally important for social care and a restrictive immigration policy will make this harder.

- As a major employer, typically providing better pay, terms and conditions, and career progression than social care can afford, the NHS has a significant impact on the social care workforce. More must be done to support social care – for instance, matching pay increases in the NHS would cost £1.7bn by 2023/24.

Note: All staff numbers referred to in this long read are full-time equivalent (FTE) unless otherwise stated. The FTE measure takes into account not just the number of people working, but also the hours they work, allowing us to compare like-for-like and understand the amount of care delivered.

Health and social care workforce

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more