Waiting for care

Understanding the pandemic’s effects on people’s health and quality of life

26 August 2021

About 14 mins to read

Key points

- The effects of the pandemic should not be measured in mortality alone. The suspension of routine NHS care has affected people’s health and wellbeing – with the significance of this depending on the type of condition or treatment delayed.

- For some conditions, a delay in care will make little or no difference. For others, a delay could lead both to living longer in pain – worsening quality of life – and/or a deterioration in their condition. This analysis explores the implications of this via two case studies – hip replacements and diabetes.

Hip replacements

- The NHS in England typically carries out 330 elective hip replacements a day. This fell to an average of between one and two a day during March and April 2020. Recovery began in May 2020, but with marked differences in the pace and extent of recovery in different regions of England – with only London recovering to pre-pandemic numbers by the end of 2020.

- In 2020, as a result of the pandemic, 58,000 fewer people than usual had a hip replacement and are therefore waiting. Those waiting are particularly likely to be in certain regions of England (the North West and the South West both have 50% fewer admissions than usual), are slightly more likely to be older and slightly more likely to be living in deprived areas. In London there has been only a 15% reduction in admissions for the least deprived area, compared with 30% for the most deprived.

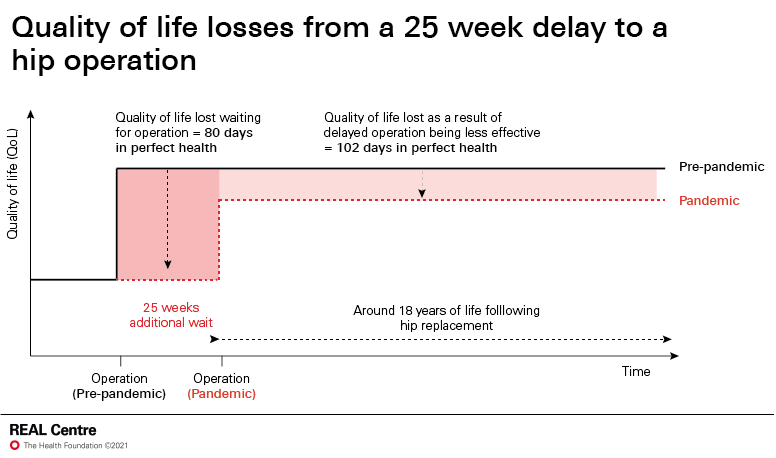

- As of January 2021, 58,000 people had waited an average of 25 additional weeks for their hip replacement. An average individual waiting for an extra 25 weeks suffers quality of life losses during the waiting period equivalent to 80 days in 'perfect health'; and post-surgery losses equivalent to 102 days. This means that, across the English population as a whole, we have lost the equivalent of 29,000 years of life spent in perfect health.

Diabetes

- In England, there were around 26% fewer new cases of type 2 diabetes in 2020 than 2019, amounting to around 40,000 missed (or delayed) diagnoses. Referrals to diabetes nurses and education programmes – which help people to manage their diabetes – were also 35% lower in 2020.

- Overall, these impacts are likely to have been less significant than for hip replacements. Missed diabetes care, particularly for those who have been diabetic for some time, does not necessarily lead to a significant deterioration in health or quality of life. We identify three vulnerable tipping points in the diagnosis of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and in the prevention of type 2 complications, where the risks of missed care are most acute.

Further reading

Waiting for care

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more