Where does the 2019 Spending Round leave health and social care, and the nation’s health prospects?

Where does the 2019 Spending Round leave health and social care, and the nation’s health prospects?

6 September 2019

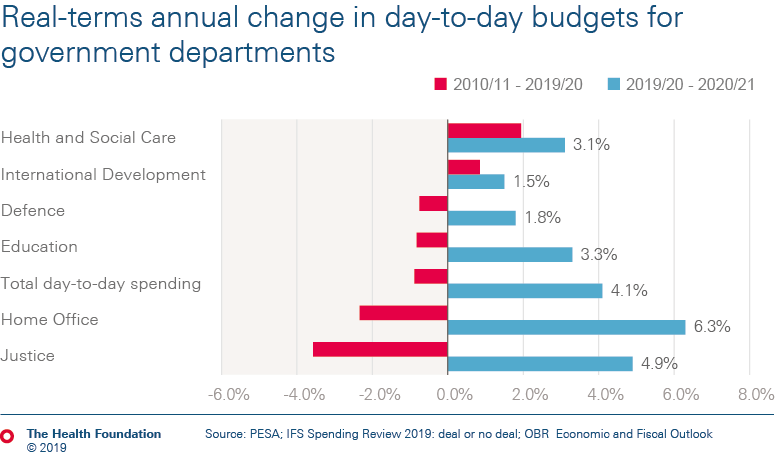

The Chancellor stated that the 2019 Spending Round 'turned the page on austerity', with an overall, real-terms increase in departmental spending of 4.1%. But with investment in the services and infrastructure needed for people to lead healthy lives at rock bottom, the question is whether the new spending is enough – and in the right places.

The NHS has been a relative winner in public spending over the last decade, although funding growth has been at a much lower rate than demand and cost pressures.

But governments have chosen to prioritise health spending on front-line services over investment in key but less visible spending, such as training and developing the NHS workforce, on buildings, equipment and technology and crucially on support for services such as smoking cessation which keep people healthy.

Health spending pressures are rising in part due to the ageing of the population. This results in similar, if not greater, pressures on adult social care. But while the health budget grew over the decade, adult social care spending fell.

In this long read, we explore three key areas:

- the wider determinants of health (including the public health grant)

- adult social care

- The Department of Health and Social Care.

So: is the new spending enough – and is it in the right places to create the long-term conditions that keep people healthy?

Where does this leave the balance between NHS and adult social care spending?

And what does it tell us about the government's commitment to back The NHS Long Term Plan with the investment needed to improve care and deliver value for money?

Earlier in the year, the Government announced plans to invest in artificial intelligence to improve the prevention, early diagnosis and treatment of chronic diseases. The Spending Round confirms the Government will invest £250m in the programme, of which £78m comes in 2020/21.

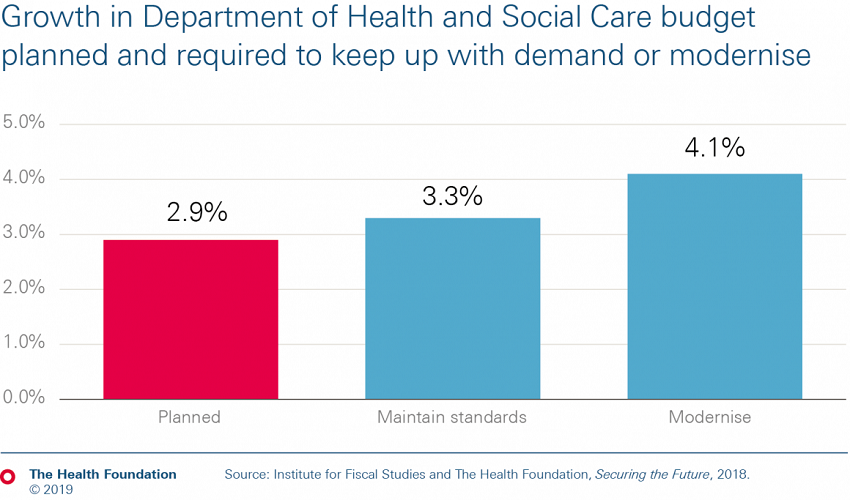

This 2.9% growth for DHSC is below projections by the Health Foundation and the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) that just to maintain current standards of care with a growing and ageing population and a rising burden of chronic disease will require total health spending to increase by 3.3% per year. And it is some way short of the 4.1% required to invest in improvements in the health service.

The capital budget is confirmed to be £1bn higher than previously planned for this year, at £7bn, but with no growth next year – standing at £7bn again in 2019/20 prices. While the increased budget this year is an improvement on recent years, it falls well short of the levels of investment required to make significant inroads into the maintenance backlog of £6bn, and leaves us lagging behind comparable countries when it comes to spending on health care capital.

While a multi-year capital settlement is promised, it is hard to see when this happens given the current political uncertainty.

The capital budget of the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) is used to finance long-term spending in the NHS, such as new buildings, equipment and technology. It also covers research and development, and some maintenance and upgrades to keep everything running smoothly.

Capital spending is a critical input in health care, with new technology able to transform services and improve workforce productivity.

Social care

Health care

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more