How debt can affect health during the cost-of-living crisis

20 November 2023

Key points

- Being in problem debt is associated with worse health outcomes. People in problem debt are three times as likely to report that their health is ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’ (21% compared with 7% for those not in problem debt).

- People struggling with debt can have less income available to spend on health-promoting activities, can experience stress and worry about being able to cope with repayments and engage in health-harming behaviours as a coping mechanism – all of which can affect their health.

- Worse health also increases a person’s likelihood of experiencing persistent debt problems. Only 56% of people with poor health and a heavy debt burden no longer had one 4 years later, compared with 71% of people in good health.

- The cost-of-living crisis is far from over. Although inflation rates have started to fall, the Consumer Prices Index was at 4.6% in October 2023 and price levels remain significantly higher than 2 years ago. Food and energy prices were respectively 28% and 22% higher in October 2023 than in October 2021.

- The combination of sustained high price levels and higher interest rates risks worsening people’s problem debt and, as a consequence, their health.

- Household indebtedness has not increased compared with pre-pandemic levels. However, evidence shows that there have been different impacts from the cost-of-living crisis across the UK population. By March 2023, 19% of adults in households with lower incomes were behind on priority bills and 23% had no savings. Both factors put them at risk of falling into problem debt.

- Government needs to focus on alleviating repayment requirements for debts to the public sector, especially through Universal Credit deductions, and ensuring benefit rates rise in line with September inflation to support the incomes of the poorest households.

Introduction

The cost-of-living crisis is far from over. Although the headline rate of inflation has started to fall, rates remain high and above the 2% inflation target, with the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) at 4.6% in October 2023. Inflation rates have also been high for more than 2 years, leaving price levels substantially higher than in 2020.

Higher prices – especially when income growth has not kept up – impact health directly through higher costs of essentials but also indirectly through problem debt. Increased living costs can mean debt repayments take up a greater share of household income, leaving people struggling to cope with paying them and/or with less money for health-promoting activities.

So far, the amount of outstanding debt as a proportion of incomes is lower than pre-pandemic levels. However, for some, the impact from both the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis has been acute – in March 2023, 26% of adults surveyed reported using credit cards and overdrafts to make ends meet, and 19% of respondents living in households with lower incomes were behind on priority bills.

How debt can affect health

Debt is not inherently good or bad for individuals and their health. Taking on debt can be useful to maintain household spending when income is temporarily low or to bring forward the purchase of certain goods and services, such as taking out a mortgage to buy a home.

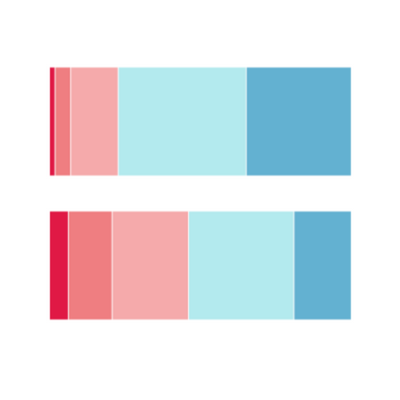

It is when people struggle with repayments that debt can become detrimental to mental and physical health. Figure 1 shows that there is a strong relationship between struggling with debt and reporting worse health. People in problem debt are twice as likely to report their health is ‘less than good’ (46% compared with 23% without problem debt) and three times as likely to report their health is ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’ (21% compared with 7%).

Figure 1

Debt can affect health in different ways:

- Struggling to meet debt repayments can act as a stressor, a ‘hardship or demand’ that can lead to adverse mental health outcomes (for example, depression) and physiologically harmful stress responses. Some evidence suggests that it is worry about debt rather than the debt itself that drives worse health outcomes.

- Experiencing stress about debt can lead people to engage in health-harming behaviours as coping mechanisms, such as problem drinking and drug use.

- Meeting debt repayments means having less money available to spend on health-promoting goods or activities. Our previous analysis suggests debt repayments can in effect reduce available income to below the poverty line for a significant number of people.

This long chart uses different measures to represent when repaying debt becomes unsustainable and, as such, potentially detrimental to health.

According to the Office for National Statistics definition, used in the Wealth and Assets Survey, a household is classified as being in ‘problem debt’ if they experience a liquidity or solvency problem.

- A liquidity problem occurs if either debt repayments represent at least 25% of net monthly household income and at least one adult in the household reports falling behind with bills or credit commitments, or the household is currently in 2 or more consecutive months’ arrears on bills or credit commitments and at least one adult in the household reports falling behind with bills or credit commitments.

- A solvency problem occurs whenever household debt represents at least 20% of net annual income and at least one adult considers their debt a heavy burden.

‘Perception of debt as a heavy burden’ is a measure based on a specific question asked as part of the Wealth and Assets Survey. A person is classed as living in household that considers their debt a heavy burden if at least one adult within the household considers keeping up with the repayment of debts and any associated interest payments a heavy financial burden.

The vicious cycle of problem debt and health

Not only can problems with debt have a detrimental impact on health, but being in poor health also affects a person’s likelihood of experiencing persistent debt problems. Figure 2 shows that of people in poor health who considered their debt a heavy burden in 2014 to 2016, 44% still considered it a heavy burden between 2018 and 2020, 4 years later. This compares with 29% of people in good health still considering debt a heavy burden after 4 years.

This suggests people in good health are able to escape debt struggles faster. It also points to a dangerous cycle between debt and health: perceived heavy debt burden is associated with worse health, and worse health increases the likelihood of remaining stuck feeling debt is a heavy burden, which leads to a further deterioration in health.

Figure 2

How the cost-of-living crisis might affect problem debt

The higher cost of everyday essentials – such as food and utility bills – shrinks the income people have available to cover debt repayments, especially families living on lower incomes.

Inflation rates began rising in March 2021 and stayed above 9% between April 2022 and March 2023. Although rates have now started to fall – with October CPI at 4.6% – rates remain historically high and well beyond the 2% inflation target.

As Figure 3 shows, the increase in prices has had the greatest impact on essentials – with prices of food increasing by 28% between October 2021 and October 2023 and prices of energy and housing increasing by more than 22%.

Figure 3

Everyday essentials are now unaffordable for many. The Financial Fairness Trust found that 23% of households were struggling to pay for food and other essential expenses in May 2023 – almost double the proportion in October 2021 (13%).

These struggles are unlikely to subside as we head towards the winter months, as 1 in 3 households will see higher energy bills compared with last winter, and 13% of households will see energy bills rise significantly by £100 or more.

Households with lower incomes continue to be most affected, as they spend a greater share of their budgets on essentials. This leaves lower-income households with less disposable income for non-essentials, including debt repayments. For those with existing debt who receive Universal Credit, this is exacerbated by direct deductions from their Universal Credit allowance to pay for existing debts – around half of Universal Credit households have some form of deduction from their benefits.

Although households with lower incomes are less likely to hold debt, they are more likely to spend a higher proportion of their income on debt repayments. As their income is currently stretched to cover the higher costs of essentials, they are more likely than households on higher incomes to feel pressure from existing debt repayments. They are also less likely to have savings to fall back on and so may need to rely on increasing debt to maintain their standard of living.

This could lead to more households with lower incomes feeling that their debt is a heavy burden or falling into problem debt, exacerbating existing inequalities in the prevalence of debt problems:

- Almost 1 in 5 (17%) working-age people in households with the lowest 10% of incomes have problem debt, compared with just 1 in a 100 working-age people in households with the highest 10% of incomes.

- Almost 1 in 4 (23%) working-age people in households with the lowest 10% of incomes consider debt a heavy burden, compared with less than 1 in 70 working-age people in households with the highest 10% of incomes.

Figure 4

Perception of debt as a heavy burden

Higher prices may lead households to be increasingly concerned that their debt will become a greater burden in the future.

Between 2004 and 2021, the trend in the proportion of adults who perceived debt as a heavy burden followed inflation very closely. When inflation fell, the proportion of people who felt debt to be a heavy burden also fell, and vice versa.

Comparable data is not yet available beyond 2021, but the proportion of people who perceive debt as a heavy burden could have risen, given inflation rates remained high over the past 2 years.

Figure 5

Higher interest rates and debt repayments

Although mortgage and consumer credit arrears have remained relatively low, the Bank of England reports that the debt advice charity sector has indicated that the scale of difficulties experienced by those seeking debt advice has increased.

Increases in the Bank of England base rate – now 5.25%, the highest since 2008 – aimed at reducing inflation will make it more costly to repay debt. This higher base rate will feed through to loans and credit card interest rates.

The risk of increased debt problems is not solely among households with lower incomes. Households with mortgages will continue to move onto higher interest rates throughout 2023 as they renegotiate existing fixed-rate deals. This might increase the proportion of households likely to experience difficulties meeting their mortgage repayments and repaying other debts.

Higher mortgage rates will also affect private renters – who are more likely to be on lower incomes – as buy-to-rent landlords pass on the costs of higher mortgages.

The likelihood of struggling with debt also varies by region. People are more likely to experience problem debt in the West Midlands, London, South West and North East. The perception of debt as a heavy burden is more common in London, the West Midlands and North East.

Figure 6

Have debts been increasing during the cost-of-living crisis?

Higher prices can affect the debt burden not only through repayments becoming unaffordable, but also by increasing people’s likelihood of taking on new debt to cope.

Different indicators point to the demand for credit growing. Consumer credit use has been increasing after the slowdown observed during the pandemic. Evidence from surveys also suggests that people are turning to debt to cope with the increased cost of living, as about a fourth of adults reported borrowing more money or using more credit than usual between June and July 2023.

Despite this, the amount of outstanding debt as a proportion of people’s incomes remains below pre-pandemic levels. This might be partly explained by the fact that households have been able to rely on higher-than-expected savings to cope with the cost-of-living crisis as a result of increased savings and debt repayments during the pandemic.

This broader picture, however, masks differences across incomes, as households in the lowest fifth of incomes were twice less likely to increase their savings during the pandemic compared with households in the highest fifth.

People’s level of savings has been shown to be a good predictor of whether they will take on formal debt or fall into short-term debt (such as missing priority bills). In March 2023, 48% of people with savings of £1,000 or less had to use a credit card, and 14% were behind on two or more priority bills. Among people with savings of at least £1,000, 19% had to use a credit card and 3% were behind on bills.

Conclusion

Although inflation rates are now coming down, the cost-of-living crisis is not over. Price levels – particularly for essentials – have risen substantially over the past couple of years.

Financial support from government has helped, and will continue to do so through the winter, but many families have struggled and face another grim winter of high energy costs and food bills.

The extent to which families fall back on debt to manage the cost-of-living crisis or struggle to cope with existing debt poses a risk to their health, a fact that can sometimes be forgotten amidst the focus on the more direct impact of high food and energy costs.

Households with lower incomes are at the greatest risk of struggling with debt, as they have less savings to cope with price-level increases and, for those with debt, repayments make up a larger share of their incomes. This is likely to contribute to widening existing health inequalities.

Efforts to mitigate the impact of debt problems for those with existing debts are helping, such as the introduction of Breathing Space in 2021, the Statutory Debt Repayments Plans due in 2024 and the Mortgage Charter agreed in September 2023 (although that might benefit from being extended to buy-to-let landlords).

However, as our previous analysis suggested, recovery of debts to the public sector remains aggressive relative to the private sector, particularly the deduction of debt repayments through Universal Credit. This is a particularly pressing issue given that households with lower incomes are at greater risk of problem debt. How the system treats such households risks making an already precarious situation much worse.

Longer term, the focus of policy intervention should be on supporting people to have financial resilience to ensure they do not fall into problem debt in the first place. This should include increasing next year’s benefit rates in line with September inflation rates to reflect higher price levels. It should also include restoring the Local Housing Allowance to cover 30% of private rents.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more