Interpreting the latest life expectancy data

15 February 2024

About 12 mins to read

Key points

- The latest estimates of period life expectancy at birth for the UK show a fall from 2017–19 of as much as 0.7 years for males (to 78.6 years) and 0.4 years for females (to 82.6 years) by 2020–22. This reflects higher than average mortality rates due to the pandemic.

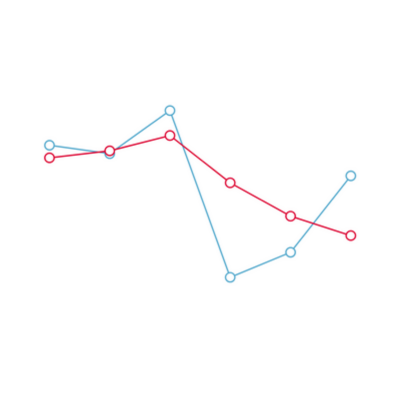

- In the decade leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, a long-term trend of improving mortality rates stalled. This is illustrated by a slowdown in period life expectancy gains. If the pre-2012 trend had continued period life expectancy at birth would be 3.3 years higher for males and 2.5 years higher for females in 2022.

- Inequalities in life expectancy remain wide and have been entrenched and exacerbated by the pandemic. The gap in life expectancy between the local authorities with the highest and lowest life expectancy was 7.4 years in 2017–19 and it grew to 8.7 years in 2020–22. More-deprived local authorities and local authorities in the north of England tend to have the lowest life expectancy.

- Although people born today are still expected to live for longer than older cohorts, they are not expected to live for as long as previously thought. People born in 2020 were expected to live to 93 years in 2010-based projections and are now expected to live to just 89 years in 2020-based projections – lower than in 2002-based projections.

- The UK’s life expectancy lags behind many other advanced nations leaving plenty of room for improvement. Strategies for a future government to boost life expectancy should include addressing health inequalities to close life expectancy gaps between different areas and ensuring people’s health is maintained through their lifetime by investing in the building blocks of health, including adequate incomes, decent housing and good work.

Further reading

Interpreting the latest life expectancy data

1. Introduction

2. How has life expectancy changed over time and what do the latest estimates show?

3. What do inequalities in life expectancy across the UK look like?

4. How does life expectancy vary by deprivation level?

5. What does future life expectancy look like and how has that changed over time?

6. What has driven life expectancy improvements in the past and what are the opportunities now?

7. What lies ahead?

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more