The (underdeveloped) power of data

3 December 2023

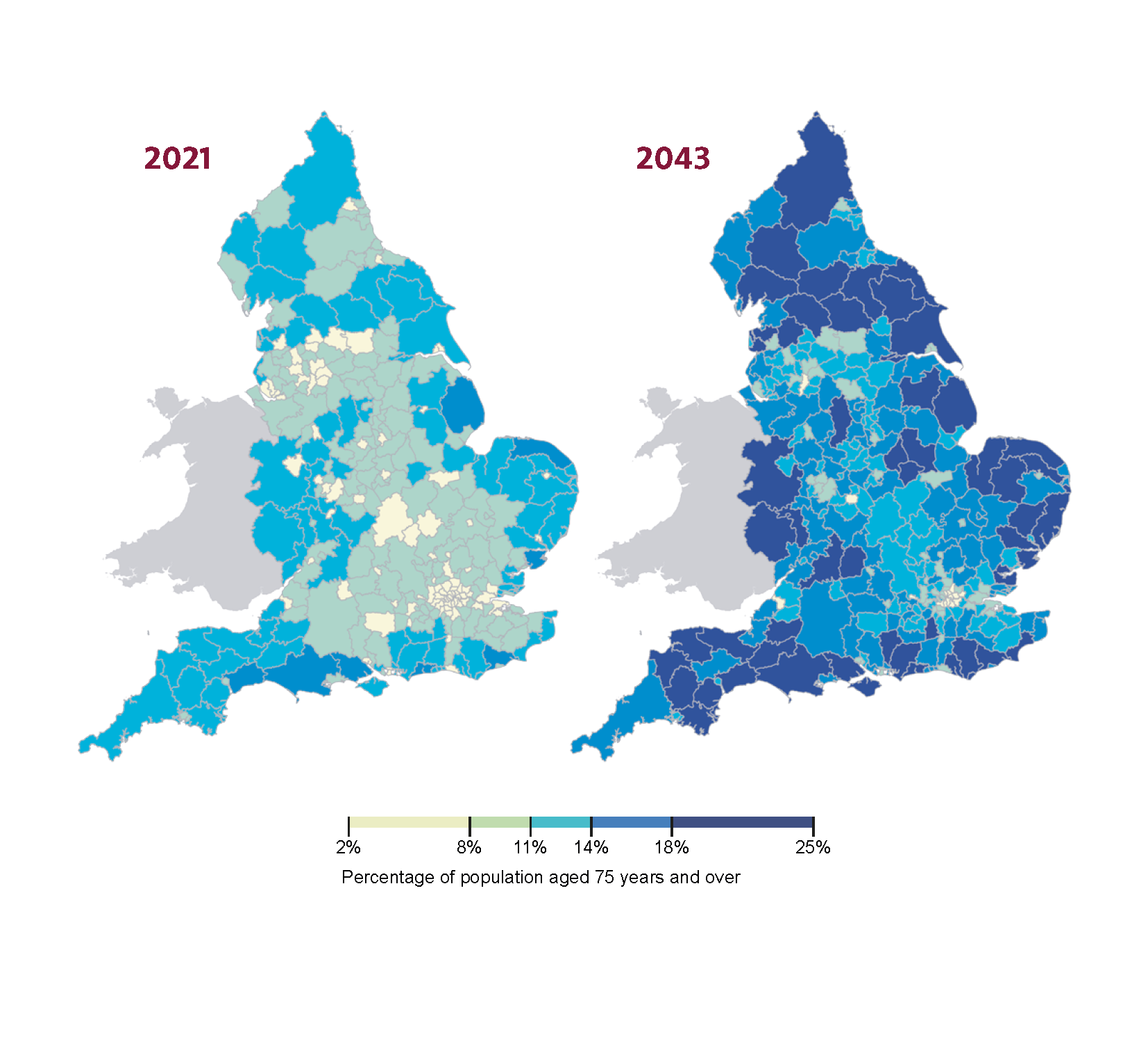

Have you seen the cover of the Chief Medical Officer’s annual report? Crash, bang, wallop what a chart – if a chart makes it onto the report cover, you know it’s a striking one. It is etched into my brain…

…and now it’s etched into yours (if you hadn’t already seen it).

Through complex analysis, the CMO’s report (subtitled ‘Health in an ageing society’) sets out a clear challenge facing the UK. The authors used research to build a narrative that follows a simple and compelling logic:

To create this insight, the authors cleverly used multiple datasets, linking the implications of differences in self-reported health with population projections at a local level.

The geographical point is very powerful, but the authors had to leave some other aspects unexplored. For example, in their analysis of demand for health and care services, they are limited to discussing age (the number) while repeatedly highlighting that chronological age isn’t the same as biological age. By this they mean that age, as a number, doesn’t predict a person’s health very well.

What is biological age?

Biological ageing, to get technical, is the time-dependent functional decline of an organism; it increases risk of illness and death. The rate of decline is not uniform across people (or any organism for that matter). Lots of things have a role in slowing or speeding up biological age, including our genetics, the wider determinants of health and medical intervention.

But what does such ageing mean on a human level? Whether a person lives to 80 years old, or (even better) does so in good health, is determined by the 80 years of that person’s life and all that has gone with it.

From national government to local councillors, it’s good to think about how many octogenarians will live in your parish, but that doesn’t tell you all you need to know about the health and other public services you will need.

So why focus on age?

Age is a key part of the CMO’s report, and it has to be – because of the data. The pool of evidence that policymakers can use is limited by the questions researchers can answer, which in turn is limited by the data that we have access to. So, while ‘more older people’ implies greater need, such conclusions lack precision. This report (and most other UK research) relies on self-reported measures of ‘general health’ from surveys.

Ideally though, we would be able to answer questions like: what health conditions will be most prevalent? Do we need more diabetes management in Birmingham or Bath? What about chronic pain – is that driven by age-related arthritis or something else? What combinations of conditions will there be?

This summer we tried to answer these questions at a national level. We published Health in 2040, looking at the number of people living with ‘major illness’ (defined by severity of disease and demand of health care), and we projected that this would increase by 2.5 million (37%) by 2040. Our analysis also showed that most of the changes in health care needs would be driven by exactly the population change that the CMO’s report highlights.

The data we use (the Clinical Practice Research Datalink, or CPRD) are incredibly detailed and provide previously unknowable insights into multimorbidity, ageing and inequality. While there is no single measure of biological age, such data can reveal more about it. We’re currently looking at how health-related outcomes, driven by differences in biological age, are different depending on the level of deprivation where you live (our report on inequalities will be published next year). But a key limitation to this work is that because of the data, we cannot be geographically precise in the way that the CMO’s report is.

Why is good data useful?

It is the responsibility of national policymakers and integrated care systems and their boards (local health commissioners) to manage changes in ill health and respond appropriately. The pool of available funding and other resources (like NHS workforce and money for maintenance) is determined by national government, with most of the funding then allocated to local health and care systems to meet local needs.

Planners and policymakers at all levels need up-to-date local information about their population’s health needs, with analysis of how this is likely to change in the future, to be able to make decisions effectively. However, in many areas, access to data, and the skills and capacity needed to turn data into meaningful insight, is limiting. Our Health in 2040 report presents data from England, at a national level. The most common questions I have received in response, in person and in my inbox, are, from national bodies: ‘What does this mean for activity and costs?’ and at a local level, ‘Can you show results for my local authority, for my ICB, my city?’.

The challenge is to make sure the right resources are in the right place. For that to happen we need good quality, up-to-date information at the right time, in the hands of people doing the planning. While there is promising linkage of data on local health and wider determinants, previous nationally-driven attempts to gather data to inform these difficult decisions has not been smooth. Data protection and patient safety remain paramount.

My colleagues’ study of public attitudes found that the UK public is, on balance, happy for health data to be used outside direct care, such as for research or to develop new medicines. But with around 1 in 5 people resistant to their data being used in these ways, it is clear that policymakers, health care organisations, researchers and industry must work to grow trust in the use of health data.

With better data, reports like the CMO’s (and ours) could deliver precise answers to concrete, pressing questions we are facing for our future health.

Precision is key – so let’s develop the data

The CMO’s report, with its powerful visuals, points out the problem: that to foster good health in an ageing and unequal society we will need to do many things better in all areas of public policy. Not just for a certain group, and not just by the NHS.

However, the report speaks more about direction than magnitude. In the coming years, as the immediacy of the growing pressure on health and care services presents itself, more precise answers would be very helpful indeed.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more