Understanding and sustaining the health care service shifts accelerated by COVID-19

Understanding and sustaining the health care service shifts accelerated by COVID-19

15 September 2020

Key points

- The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has led to significant changes in how NHS services are delivered and used. This has seen an acceleration of policies that have previously only made incremental progress.

- Service shifts have affected the whole care pathway. This includes changes to health promotion and support for vulnerable people in the community; remote consultations in primary and hospital care; new ways of receiving emergency acute and mental health services; and new collaborations across the health and care system.

- A number of ‘enablers’ made these changes possible despite the huge strain on the system. These included local freedoms to implement changes within national guidelines, more time for clinicians to innovate and permissive ‘air cover’ from regulators to do so.

- Barriers to sustaining these ‘service shifts’ include fears of digital exclusion for some patients, challenges arising from collaboration across organisations and the potential fragility of the new community support networks because of financial pressure on the voluntary sector and future loss of volunteers.

- As the NHS moves into the recovery phase and starts to address the backlog of care and unmet need, it will need to maintain openness to radical innovation and learn from what made such a response possible. The need to improvise and adapt will continue for the foreseeable future.

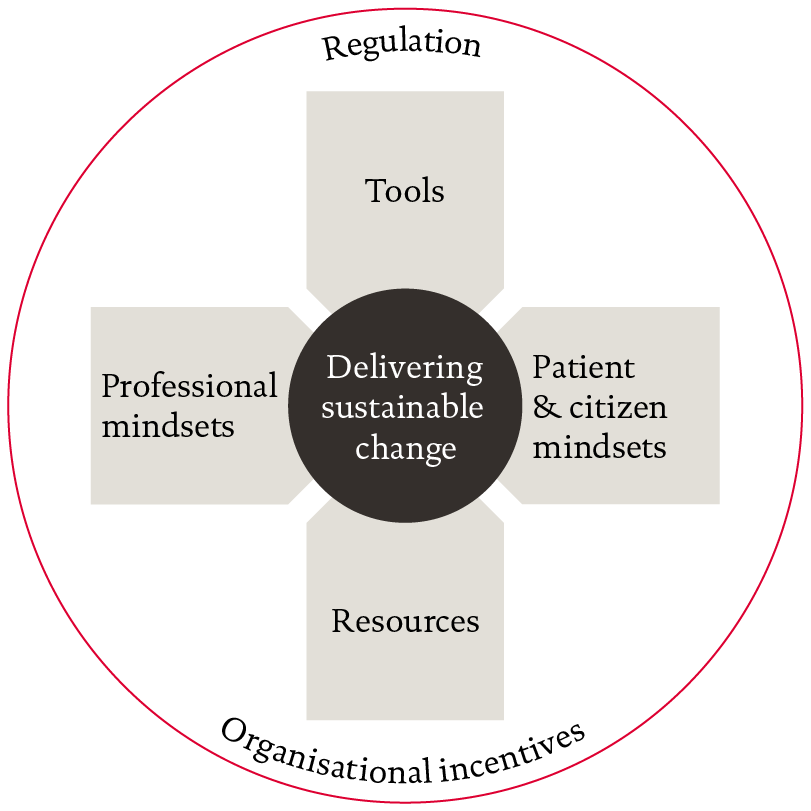

- A model for sustainable change will need to bring together different factors to maintain new ways of working. These factors include having the backing and confidence of both clinicians and patients in service shifts forged during the crisis period, the availability of tools and resources and the alignment of systems of regulation and incentives.

| Promotion/Prevention/ self management | Primary and community | Specialist diagnosis and treatment | |

| Patient-clinician shifts |

|

|

|

| System shifts |

|

||

Source: stakeholder interviews, grey and other literature.

Mindsets

At the centre of this model lie the ‘mindsets’ of NHS staff . These mindsets comprise the beliefs and assumptions generated by experience. Clinicians wield significant discretionary power, including in some circumstances the power not to act nor to comply with demands. If the beliefs and assumptions held by clinical staff are not aligned with the assumptions that underpin the new service models, then the sustainability of those new ways of working is threatened.

While the mindsets of clinicians are important, so too are the mindsets of patients and their carers. If patients do not accept new modes of care they have a number of options including: bargaining (eg negotiating ‘work-arounds’ with clinicians that maintain old ways of working); opposition (eg formal protest including through the political system) and exit (simply not presenting for services).

Examples of the beliefs and assumptions that might be needed for these service shifts to be sustained are illustrated in Figure 3. Some of these beliefs and assumptions may have been largely established through the pandemic, but others remain in doubt, with more convincing required. Especially as debate shifts to longer term arrangements, professionals may question whether resources will be shifted to support new service models, or fear that careers will be less satisfying and smack of ‘call centre medicine’. Patients and citizens may need reassurance that services have been designed with patient input and priorities in mind.

| Likely largely in place | Likely still required | |

| Professional mindsets |

|

|

| Patient and citizen mindsets |

|

|

Tools and resources

For change to be sustained, mindsets need to be supported by the right resources and tools. Tools include widespread access to digital consulting software, the use of ‘advice and guidance’ from hospital consultants to GPs (especially local developments which ensured interoperability with GP systems) and the adoption of relatively inexpensive devices such as pulse oximeters and blood pressure monitors and apps through the NHS app store to support patient self-management. Even widely available tools, such as WhatsApp, have been effective in connecting hundreds of neighbourhoods to support vulnerable people and shielding groups.

The availability of funding has also proved important in bringing about change – the NHS was essentially offered a blank cheque – but this period of plenty will not continue indefinitely. New activity flows and responsibilities will need to be underpinned by new resources. Some new services (such as step-down from hospital) relied on redeploying staff from services that had temporarily been suspended. Realism is needed about the workforce needed for both new and restarted services. Testing and refining new service models will itself require additional resources.

It is also clear that the time and support for learning, collaboration and improvement is also a key resource. Additional time was created by reductions in activity levels and bureaucracy, and ways to protect this time will need to be found if these changes are to spread, deepen and sustain.

Regulatory framework and organisational incentives

Many of the service shifts identified in this long read introduce new risks, such as patient assessment without physical presence, new types of staff substituting for another and rapid relocation from one setting to another. Many interviewees said the special measures introduced by regulatory authorities in relation to clinical risk and information governance were important. Without continuing regulatory ‘air cover’ changes are unlikely to sustain. Regulators and professional bodies could go further to support embedding change, by setting out more definitive guidance for practitioners (on effective digital consultation for example).

Lastly, NHS and care organisations need to face incentives that do not work against the sustainability of service shifts, and preferably support them. Financial incentives have a part to play and there is an opportunity with the suspension of the current NHS financial regime to ensure that whatever replaces it is well designed (for example, for many years the pricing of outpatient appointments discouraged hospitals from offering virtual consultations and ‘advice and guidance’ to GPs in preference to formal clinic appointments).

Other organisational incentives matter too, such as formal targets, performance management regimes and informal measures, such as what is celebrated or leads to career advancement. A common theme from evaluations of new ways of working suggest that local teams are inhibited if senior management faces different organisational incentives or is simply distracted by competing priorities.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more