What do technology and AI mean for the future of work in health care?

What do technology and AI mean for the future of work in health care?

Key points

- Recent developments in artificial intelligence (AI) have sparked fears about the potential threat to jobs in many industries, including health care. Yet policy papers such as the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan (2023) and Topol Review (2019) imagine a more positive future for the role of technology in health care work. Drawing on labour market modelling, this long read analyses what makes health care different from other industries predicted to be more heavily impacted by new technologies.

- While unlikely to lead to widespread job losses in health care, technology is transforming, and will continue to transform, the nature of work. The right technologies, properly implemented, can not only extend human capabilities, but also enable staff to switch their time and attention to tasks where humans add more value – supporting workforce capacity at a time of huge pressure.

- We present a framework to help navigate this shifting landscape, showing how technologies can variously substitute, supersede, support or strengthen human labour. This framework can be used to understand not only how specific tasks might be affected but also how the occupational roles typically associated with those tasks might evolve.

- Role evolution should not be viewed as a passive process, but should be actively planned and shaped. We need a shared vision for how professions and occupations – as well as new roles – should develop with greater use of technology, driven not only by policymakers and system leaders but crucially by staff themselves and their representative bodies and employers, along with patients and the public. This vision must be supported by national workforce planning, education and training strategies, and more opportunities for NHS staff to signal the technologies they need.

- To support this agenda, the Health Foundation is embarking on a new programme of work to explore the opportunities that technologies present for supporting staff and improving ways of working in the NHS.

Introduction

In recent months, the question ‘Will AI take my job?’ has become ubiquitous in the media (see articles from the Guardian, the the Daily Mail and Business Insider, for example). Such headlines are of course nothing new – discussions about the threat technology could pose to the labour market stretch back centuries. But recent developments in large language models like ChatGPT have reignited the debate, sparking fears about the impact on occupations in a range of sectors, including health care.

The recent NHS Long Term Workforce Plan, however, presented a more optimistic vision of the future. Echoing the conclusions of the 2019 Topol Review on preparing the NHS workforce for the digital future, it imagined technology and AI ‘augmenting rather than replacing’ staff and described how new technologies could ‘free up clinicians’, giving them ‘the gift of time’ to spend on patient care.

Is this more positive vision justified? If so, how can it be achieved? To answer these questions, the Health Foundation is embarking on a new programme of work to explore the opportunities that technologies present for supporting health care staff and improving ways of working in the NHS. This long read unpacks what it is about health care that makes the likely impact of technology on work different from that in many other sectors and sets out an analytical framework to navigate this shifting landscape.

While our research encompasses different types of technology – such as electronic health records, health apps or AI-driven image analysis – here we have a particular focus on automation and AI, given that recent developments in these areas have renewed debates about the future of the labour market.

How will automation and AI impact on jobs in health care?

Labour market modelling suggests that the impact of new technologies will be felt differently across industries and occupations. A 2021 report by PwC predicted the risk of job displacement in health and social care from ‘AI and related technologies’ would be lower than that in many other sectors. In fact, when set against the backdrop of escalating patient demand, the report anticipated that health and social care will see the largest net employment increases of any sector over the next 20 years, with technology largely proving ‘complementary’.

There are several potential factors behind this more positive outlook – including factors that underpin the nature of health care work itself.

Technology struggles to replicate the traits or competencies in health care

Firstly, many tasks in health care are difficult to automate because they require traits or competencies that AI and other technologies currently struggle to replicate. Recent research from Open AI, Open Research and the University of Pennsylvania (2023), for instance, found jobs requiring critical thinking skills are less likely to be impacted by current large language models. Critical thinking is central to much of health care, where staff must weigh up the benefits and risks of different possibilities, approaches and solutions. For example, important nuances may be required in translating patient symptoms into diagnoses and treatments. While AI such as large language models can assist critical thinking – for instance by supporting clinicians' education, training and professional development or by distilling high volumes of research to generate health advice – this is different from actually doing the critical thinking. Other key competencies needed in health care, such as creativity and negotiating skills, are likewise difficult to automate.

Social and emotional intelligence are also essential components of high-quality care, enabling staff to empathise, communicate effectively and meet patient needs. Analysis by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in 2019 – which found that medical practitioners were one of the three occupations at lowest risk of automation – noted that health-related words such as ‘patient’ and ‘treatment’ frequently appeared in the task descriptions of jobs at low risk of automation. The ONS suggested this reflects the dimension of ‘working with people’ and ‘the value added by humans in these roles, which is difficult to computerise’. Again, emerging research indicates AI could support empathetic communication – for instance, by generating draft responses to patient questions – but this is different to being empathetic, which requires the ability to read and understand the feelings of other people, and to express and reason with emotion.

Health care is seen as intrinsically ‘human’

A second factor is that in the UK, as in many cultures, health care is seen as intrinsically ‘human’. Given the considerable value attached to the interpersonal dimension of care, some activities – such as communicating a diagnosis of serious illness or comforting a patient – cannot be delegated to machines without undermining the quality and ethos of care. To take another example, while some patients may be happy with AI making clinical decisions in areas such as triage, others might feel that having a human listen to and consider their case is an important component of being treated respectfully and compassionately. Health care is not a product, but a service that is co-designed between professionals and patients and built on trust. Thus, human relationships assume particular significance in areas like care planning, where the need for genuine partnership may pose important constraints on the use of automation.

A 2021 study from the University of Oxford looked not only at which health care activities could be automated, but also at what health care practitioners thought about the desirability of automating them. Interestingly, several activities ranked high for automation potential but low for automation desirability – typically those involving a ‘high level of physical contact’ with patients (such as administering anaesthetics or examining the mouth and teeth). Many health care tasks sit at the intersection of attending to a patient’s physical, mental and social needs, and this likely influences attitudes towards automation.

Even where a task could be automated it doesn’t necessarily follow that it should be. In the study by Open AI, Open Research and the University of Pennsylvania, researchers noted the difficulty of making predictions about the impact of large language models on activities where there is ‘currently some regulation or norm that requires or suggests human oversight, judgment or empathy’ – a description that characterises much of health care.

Few health care roles consist of wholly automatable tasks

A third reason why there is lower risk of widespread job displacement in health care is that automation applies to tasks not to roles per se, and few health care occupations consist wholly of automatable tasks. A Health Foundation-funded study into the potential of automation in primary care found that, while there were a small number of roles (such as a prescription clerk) that were likely to be heavily impacted by automation, no single occupation could be entirely automated.

Where only specific tasks can be automated, staff can adapt by focusing on other tasks or expanding their roles. Research by Goldman Sachs (2023) on the exposure of different industries to automation and generative AI predicted that the occupational categories of ‘healthcare support’ and ‘healthcare practitioners and technical’ will be largely complemented rather than replaced by AI – precisely because of the mix of tasks involved. Similarly, research by Accenture (2023) suggested that, compared to many other industries, a smaller share of health work has high potential for automation, but a bigger share has a high potential for ‘augmentation’ by technology.

How might the nature of work evolve?

Rather than job displacement, then, it seems that in many cases automation and AI in health care will enable staff to switch their time and attention to tasks that cannot be automated, and to focus on activities where humans can add more value. Given current workforce shortages and rising demand for services, it is precisely this potential that lies behind the increasing interest in what technology can do for the NHS – particularly if it could mean staff spending less time on routine admin and more on direct care.

Technology can also extend human abilities and capacity by speeding up processes, enabling greater precision, or providing greater consistency. Funded by the Health Foundation, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial College London have developed a natural language processing tool that can analyse 6,000 patient feedback comments in 15 minutes (compared to 4 days for a member of staff). With the algorithm performing analysis at huge pace and scale, staff can spend more time using insights from that feedback to improve services. The Imperial team has now scaled the innovation across nine NHS trusts, and the partnership has developed an online community of practice and a national toolkit.

Technology thus holds the prospect of not only boosting capacity and supporting staff, but in the process potentially improving job quality, for example by removing some of the burden of routine tasks. This assumes, however, a somewhat idealised vision of technological development, where the optimum solutions are made available to the NHS and then implemented effectively (in ways that acknowledge the complex realities of front-line work). The challenges of realising this should not be underestimated. Further, it should be acknowledged that ‘task switching’ – whereby staff turn to other aspects of their work or take on additional tasks when technology relieves them of others – can also create new pressures. For example, staff may require new skills or find themselves working more continually at the top of their skillset, with less routine work to act as a ‘buffer’, thereby increasing the chances of burnout. Anticipating and responding to these issues is crucial for the effective deployment of new technologies.

Despite these challenges, the opportunities for technology to improve work are recognised by many NHS staff. Polling by the Health Foundation asked staff to choose between two contrasting statements, one suggesting the primary impact of automation and AI would be positive for health care workers (improving the quality of work) and one suggesting the primary impact would be negative (threatening jobs and status). Respondents were on balance optimistic, with 45% choosing the former and 36% the latter; and this margin increased significantly among those who knew more about health care technology. There were important differences between professional groups, however. While medical and dental staff were more likely to think the impact would be positive, health care assistants were more likely to think that the impact would be negative. Given the impacts of automation and AI are likely to be unevenly distributed across the health care workforce, it is important that staff are supported accordingly.

So while fears of widespread job losses in the sector may be overstated, it is clear that new technologies will have a transformative impact on work – extending the capabilities of staff and recalibrating the mix of tasks that make up different roles. Predicting the precise impact technology will have on different occupations and professions within the sector is complex. Not only is technology constantly evolving, but health care roles are hugely varied. Each is made up of a diverse range of tasks, activities and processes, many of which could be modified by technology in different ways and to different extents. Even the same role might be deployed differently across different settings, providers and geographic locations. The key is understanding not only how technology can help staff and patients, but the potential to develop roles and ways of working as technology evolves.

A framework for navigating the impact of technology on work in health care

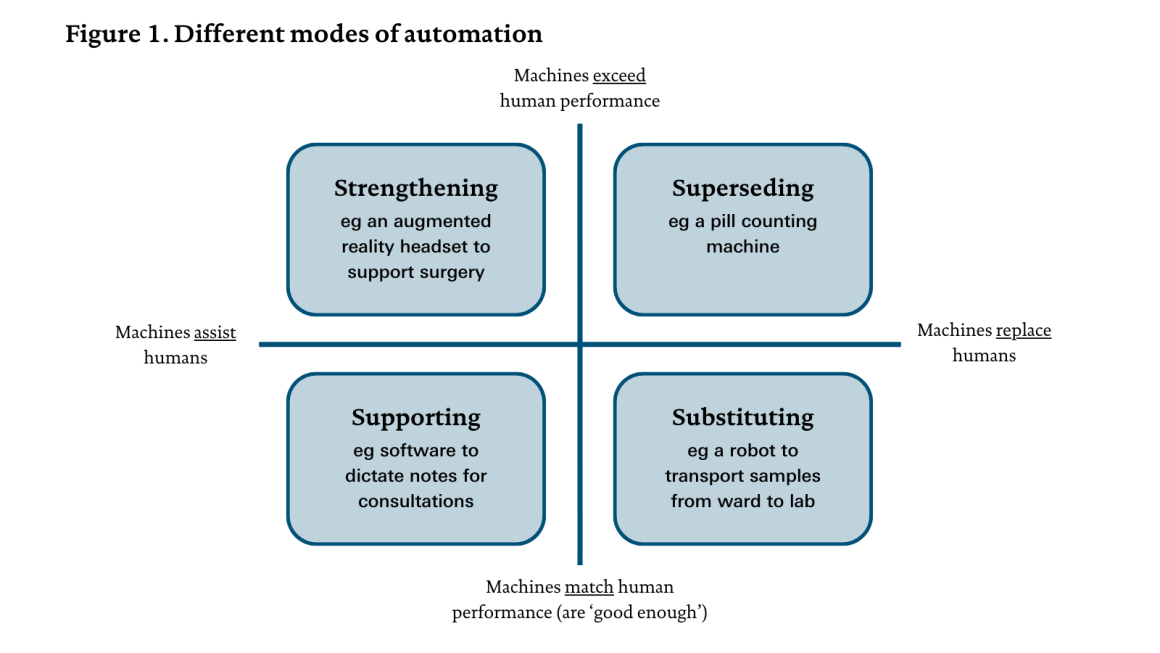

In order to explore the potential impact of technology on particular roles in the health care sector, we first need to consider its impact on the component tasks that make up those roles. Figure 1 provides a framework to support this thinking.

Task delivery and task performance can be affected by several different ‘modes of automation’. In the literature, there is often a basic distinction between ‘automation’ and ‘augmentation’. Here automation refers to where technology is replacing workers (the right side of the grid), and augmentation to where technology is assisting workers (the left side). This distinction alone doesn’t allow us to differentiate between a range of contrasting uses of technology, however. A further distinction is needed, between technology that’s ‘good enough’ for use in a real-world work environment – that is, matching or nearly matching human performance (the bottom half of the grid) – versus technology that’s deployed because it can exceed human performance (shown in the top half). In the case of ‘good enough’ technology, the primary motivation is usually to release staff capacity; in the case of technology that can exceed human performance, the primary motivation is often to improve task performance (though such technology could be deployed to release capacity too).

These distinctions allow us to identify four different ‘modes of automation’:

- substituting – when technology is able to perform a task to a similar level to human workers or to a ‘good enough’ standard, and is used to replace human workers in performing the task, thereby freeing them up to focus on other work

- superseding – when technology significantly exceeds particular human capabilities and is used to replace human input in performing a task, thereby providing an opportunity to improve task performance, as well as potentially freeing up staff to focus on other work

- supporting – when technology is used to provide additional functionality or capacity to assist a worker in performing a task, not because the worker can’t do what the technology is doing, but because the technology effectively increases their capacity or allows them to focus more on other aspects of the task

- strengthening – when technology designed to assist human task performance extends beyond human capabilities, thereby enabling improved task performance, but is not intended to operate autonomously.

For example, many of the technologies highlighted in the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan can assist staff in their roles, whether by supporting (for example, speech recognition software for clinical documentation) or strengthening (for example, robot-assisted surgery). Other technologies cited in the plan imply more direct substitution, such as automated dispensing in pharmacy or robotic process automation for routine administrative tasks.

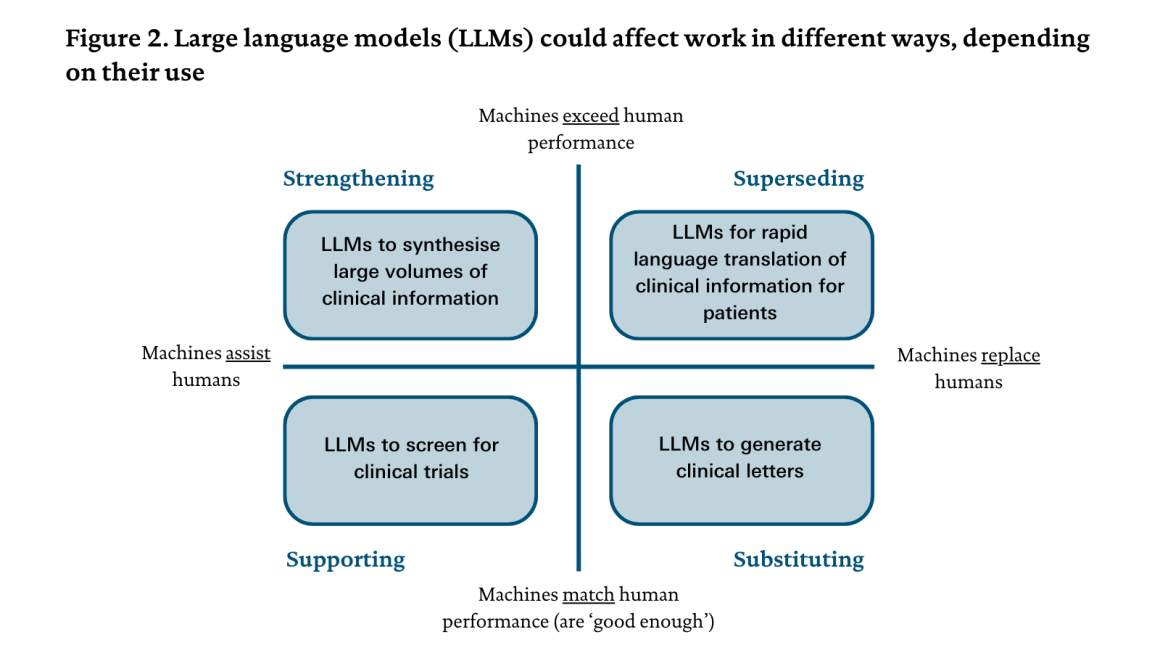

This framework is intended to categorise different uses of technology rather than technologies themselves. The same technology can be used in different ways, and the mode of automation will depend on how it is used on a particular occasion. For example, amid all the debate about how large language models might affect health care work, it should be acknowledged that they could be used in any of these four modes, as illustrated in Figure 2.

The impact of a particular technology on work can also obviously shift over time, either as the technology evolves (for example, if it gains greater computing or operational power or combines with other technologies) or as attitudes and norms regarding the use of that technology change (for example, if trust and confidence increase or decrease). Figure 3 illustrates how clinical decision support systems with different levels of capability could affect work in different ways. The diagram also highlights the potential for automated systems to shift from decision support to decision making (though in practice this would require significant clarification around regulatory frameworks and accountability). Each of these scenarios has its own potential benefits; it is not always the ‘end goal’ for a machine to reach the stage of superseding human labour, and such a situation may not be desirable or feasible.

Using the framework to understand how roles may change: a case study of the GP receptionist

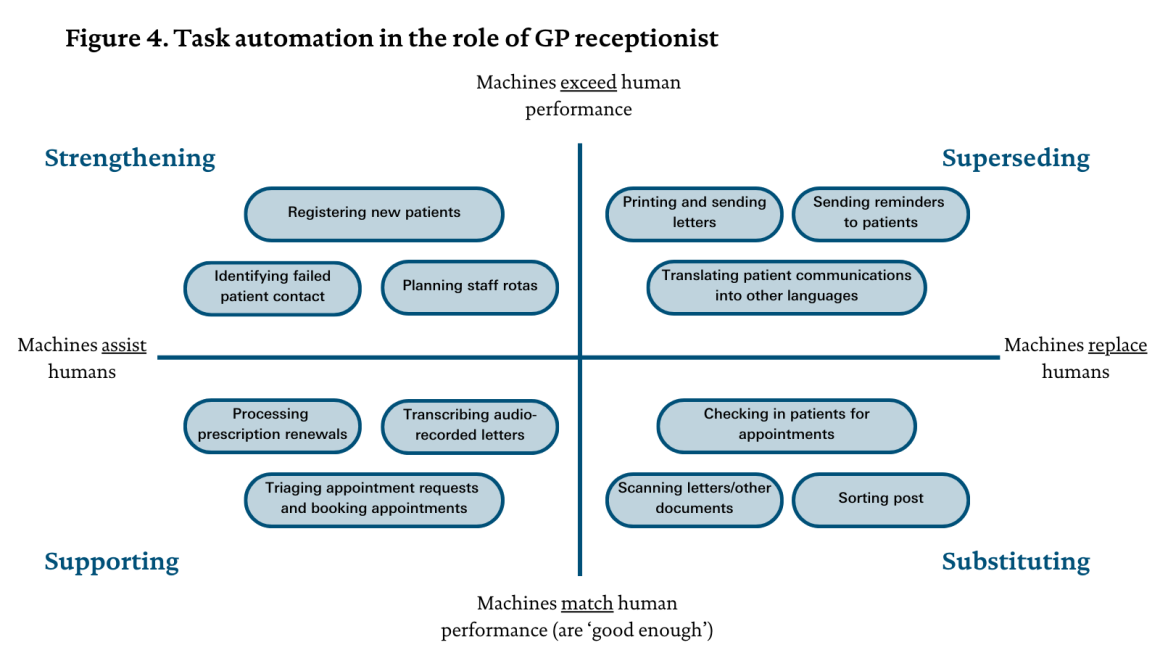

Understanding how particular health care tasks will be affected by different modes of automation can, in turn, create a clearer picture of how roles typically associated with those tasks might evolve over time. To illustrate, here we consider the role of the GP receptionist. Our work draws on a task analysis of the GP receptionist role by the Oxford Internet Institute, the Oxford Department of Engineering Science and the Oxford Martin School.

As the Health and Social Care Committee’s 2022 report, The future of general practice, highlighted, GP receptionists ‘play an incredibly important role in primary care that often goes unrecognised’. In part, the importance of the role is because receptionists are usually the first point of contact for patients seeking access to health care, but they also undertake a wide range of crucial administrative work.

Figure 4 illustrates some tasks a GP receptionist might carry out that can be assisted or performed by technology, while the list below highlights other tasks that involve a significant human component and are therefore less amenable to automation (even if technology may play some role). Situating tasks within the grid (or determining whether they sit outside it) requires finely balanced judgements about what those tasks entail and the skills that underpin them. (Of course, many GP receptionists’ work will involve other activities not captured here, and the specific activities carried out by receptionists will vary across practices.)

Note: this analysis seeks to provide illustrative examples for each of the four modes of automation. It does not attempt to capture the overall distribution of ways in which technology will impact on receptionists’ work.

Other tasks involved in the receptionist role include:

- attending the front desk to welcome people

- handling queries from patients and staff

- answering phones

- managing the practice email inbox

- helping to book appointments

- gathering information for/from colleagues and health records

- supporting communication with staff in other health care settings (such as secondary care).

The analysis indicates how automation might directly relieve the receptionist of some high-volume, routine tasks and also offer extended capabilities that open up new possibilities. This could enable the receptionist to shift their time and attention to other aspects of the task in question or to more person-centred and challenging areas of work, such as those listed in the box. For example, software that processes and standardises patient registrations could help identify new patients with specific health conditions or communication needs, enabling the receptionist to extract important insights to share with the practice team. Similarly, using software to identify those patients who have not responded to recent contact could assist the receptionist to make enquiries and check on the wellbeing of patients, some of whom may be in a vulnerable situation or facing digital exclusion.

Over time, such adjustments might lead to more fundamental shifts in the nature of the receptionist’s role (though the precise restructuring of work will naturally vary according to local circumstances). For example, there could be less focus on routine administration and a greater focus on care navigation, which would mean more time spent interacting with patients, understanding their needs and directing them to the right sources of support. Changes like this not only have the potential to reduce pressures in primary care; they could be viewed as positive by patients and staff, helping recruitment and retention as well as improving patient experience.

This case study illustrates that with greater use of technology, the task mix within roles is likely to change, with some tasks assuming more importance, others less so, and some disappearing while new ones emerge. Where this is the case, the role itself may undergo significant change and staff should be supported accordingly, for example, through dedicated training and professional development, mentoring and peer support. There may also need to be accompanying changes to regulation or guidance.

Shaping a vision for the future of health care work

With technology transforming roles, how should the health and care system respond? It is critical that role evolution is not viewed as a passive process. By using analysis like the framework above to understand how technology and AI will impact on the future of work, occupational evolution can be actively planned and shaped – not only by policymakers and system leaders but, critically, by staff groups themselves. And rather than being simply the end-users of a pipeline of technology development, staff also have a crucial role to play in signalling the types of technologies that could make their working lives easier and improve care for patients.

The recent Long Term Workforce Plan set out an ambition for NHS England to develop its ‘understanding of the implications’ of technology and AI for the workforce, in collaboration with partners. This is very welcome, but can only be the first step if the direction of travel is to be proactively shaped by the NHS, particularly those working within it.

A shared vision is needed for how professions and occupations will evolve and how new ones may develop with greater use of technology. Rather than simply being a reactive response to industry-led innovation, this vision must be driven by a collective view of what health care could and should look like in the future (for example, greater focus on prevention and personalisation), shaped by patient and public involvement. This vision should then inform public sector science and innovation strategies, as well as long-term workforce planning, and workforce education and training. So, what might this look like in practice?

- NHS staff should be empowered to play a central role in the development of this vision, in partnership with their colleagues, employers, trade unions, professional and representative bodies, patients, and the public. Ultimately, it is staff who are best placed to understand the future potential of their roles and ways of working, the technologies needed to realise this, and what aspects of their work could be enhanced or expanded as the role develops. While detailed visions will need to be developed on an occupation-by-occupation basis, there is also huge scope for professional groups to learn from one another, as well as from health care systems in other countries and other relevant sectors of the economy. Box 1 sets out work already underway by professional bodies to shape this agenda.

Professional bodies are already engaging with the rise of technology and AI, producing resources for clinical practice, establishing networks, and beginning to articulate visions for the future.

- The Chartered Society of Physiotherapists have a Physiotherapy Health Informatics Strategy and a Digital and Informatics Physiotherapy Group.

- The Royal College of General Practitioners have produced a digital technology roadmap (2019) with actions that need to be taken to realise their vision for the future of general practice, one which not only improves patient care but makes ‘GPs’ working lives easier and more rewarding’.

- The Royal College of Radiologists’ Overcoming barriers to AI implementation in imaging report (2023) proposes solutions to tackle challenges to implementing AI tools in the NHS.

- Building on their Commission on the Future of Surgery (2018), the Royal College of Surgeons of England is collaborating with NHS England and industry providers to develop a robotics curriculum.

- It is vital that all staff groups are supported to take part in this, given that the impact of AI and automation will be unevenly distributed across the workforce. Different staff groups have varying levels of voice and representation, and many – including, for example, GP receptionists, discussed above – lack formal professional networks and representative bodies. In such cases, employers and managers (for example, local practice managers and primary care networks in the case of GP receptionists) have an important role in giving front-line staff a voice.

- This agenda requires more opportunities for staff to be involved in demand signalling for new technologies – to help ensure their priorities, needs and expertise inform the design and deployment of new technologies. The NHS can do more to amplify workforce perspectives and communicate these to industry – the workforce plan’s creation of a new expert group to determine where AI can be used most effectively across the NHS is an important first step here. This should drive much greater focus on technologies to improve job quality, including technologies that support administrative tasks; our analysis shows that public funding and support are typically concentrated on clinical innovation instead.

- Policymakers have a crucial role to play in enabling this future vision including through workforce and education and training strategies. Long-term workforce planning cannot assume roles are fixed and must engage with these evolving professional and occupational identities and new ways of working. Strategies for workforce education, training and skills development must ensure all staff can capitalise on technologies now and in the future. Given the pace of change, using technologies must not only be supported by curricula at the start of health care careers, but enabled by continuing professional development too. This should include more agile, generalist digital training that reflects the versatile capabilities of technology. Professional development in other skills will also be crucial as roles develop. If someone’s job is likely to become more patient-facing, for example, then they may require support to hone specific interpersonal skills such as in shared decision-making or coaching. Mitigations may also need to be put in place to prevent ‘deskilling’, that is, the erosion of skills relating to tasks that become increasingly automated. Since the impact of automation and AI will differ across staff groups, support should be tailored appropriately, with resources focused on those who will have to make larger adjustments, and time for training made available to workers in both clinical and non-clinical roles.

Ultimately, if the NHS is to capitalise on the benefits of new technologies, a more proactive approach is needed, one which involves close working between staff, providers, professional bodies, policymakers, tech developers, and patients and the public. While acknowledging the transformative potential of technology, this approach must also recognise the realities and complexities of front-line work in the NHS, with all the pressures staff currently face, and the challenges remaining in getting basic infrastructure right.

As part of our programme of work on technology and the health care workforce, the Health Foundation will be engaging with stakeholders including professional bodies to help amplify staff voices in this debate and share practice-based insights. Closing the gap between policy and practice is critical if we are to ensure that new technologies, including AI, best serve the interests of the NHS, its staff and the public.

The authors would like to thank the following for their contributions to this work:

- Hatim Abdulhussein, National Clinical Lead for AI and Digital Workforce, NHS England

- Joanna Bircher, GP and Clinical Director of GP Excellence Programme, Greater Manchester Primary Care Provider Board

- Euan McComiskie, Health Informatics Lead, Chartered Society of Physiotherapy

- Louise Thomas, Head of Quality Improvement, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Share this page:

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more