Running to stand still: Why £20.5bn is a lot but not enough to do everything

24 August 2018

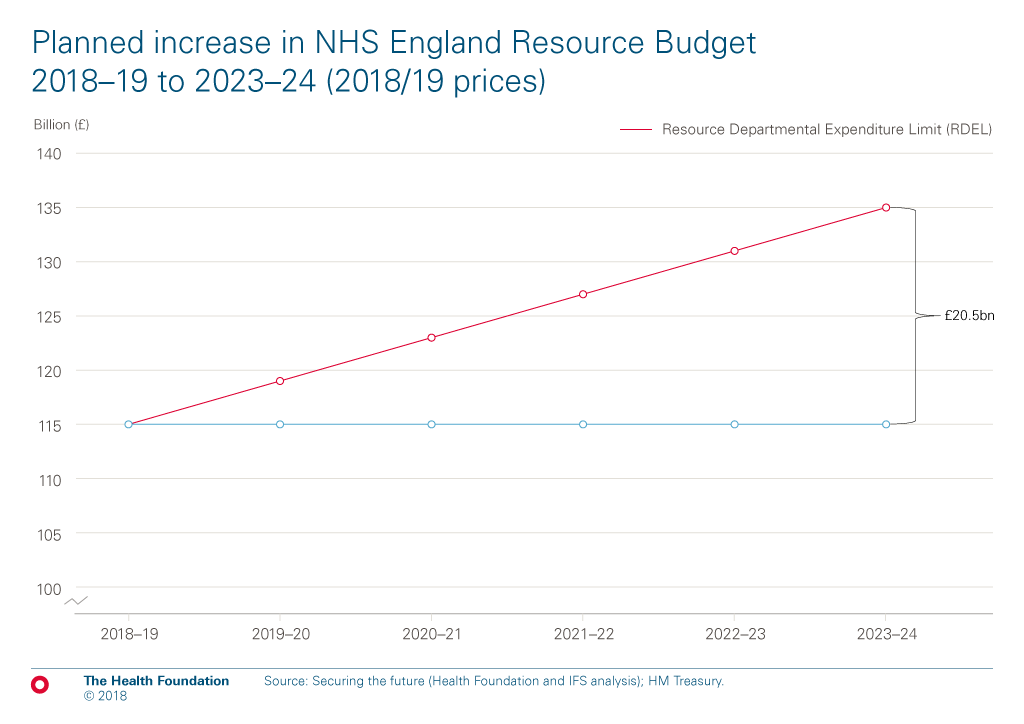

The government has announced a new funding settlement for NHS England. NHS England’s budget will increase by £20.5bn in real terms in 2023/24, rising from £114.6bn in 2018/19 to £135bn in 2023/24 (in 2018/19 prices). This is an annual average increase of 3.4% a year above inflation. The money is slightly front loaded with an increase of 3.6% next year.

Why £20.5bn isn’t enough to do everything

The funding increase announced by the Prime Minister, while substantial, is in line with estimates from the Health Foundation and Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) of the additional budget required simply to maintain current levels of quality and access to care: 3.3% a year. It is below the estimates of the funding growth of 4% a year that would be required to further improve and modernise the NHS.

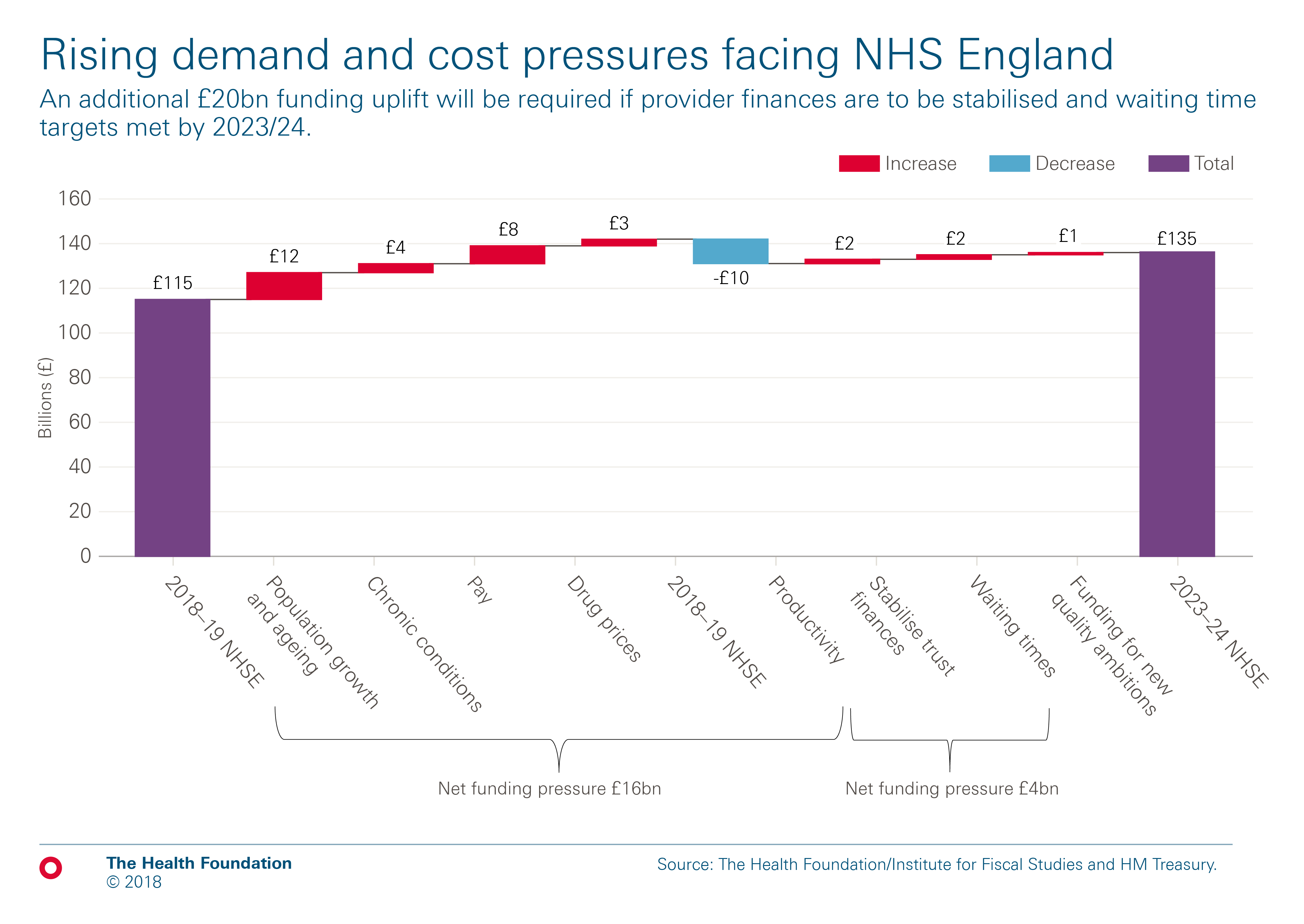

The below chart shows how the demand and cost pressures faced by NHS England will increase over the next five years. Taken together, the £20.5bn of additional funding is just enough to maintain current standards and there is very little, if any, funding for investment to improve quality and access to care.

These pressures arise from a growing and ageing population, which will add £12bn to NHS pressures. But demand is also rising as a result of the burden of chronic disease, particularly multi-morbidity. In 2015/16, one in three patients admitted to hospital in England as an emergency had five or more health conditions, up from one in 10 a decade earlier. The pressures on hospitals from patients with multiple chronic conditions have risen rapidly over the last decade. If that continues, hospital activity would increase by 14% over the next five years, consuming a further £4bn of the funding uplift. Together, demographic change and the rising burden of chronic disease are projected to add £16bn of spending.

The NHS also faces pressures from pay and rising pharmaceutical costs for new, innovative medicines. A significant proportion of the funding increase will be needed to fund real terms pay increases for NHS staff. After seven years where NHS pay has not kept pace with inflation, the government and unions have agreed a new pay deal for the million non-medical staff in the NHS, as well as a doctors and dentists deal. This is necessary as, while funding has been a serious concern, staff shortages pose a very substantial risk to the health service’s ability to sustain high quality care. One in 10 nursing posts is currently vacant. Together, pay and pharmaceuticals add at least a further £10bn of costs, giving a total of £26bn spending pressures needing to be met, in addition to the £20.5bn funding settlement.

Productivity improvements can offset some of these pressures. Productivity growth of 1% a year would reduce this £26bn by £9bn. But this still leaves around £17bn in spending pressures meaning additional demand and input costs will consume over three quarters of the extra NHS funding promised by the Prime Minister over the next five years.

In addition to these pressures, the health service has further challenges that will require funding. NHS hospitals are in deficit and the waiting times targets for A&E and planned operations haven’t been meet for 3 years. The health service has been transferring money from the capital investment budget to bridge some of the gap. Last year almost £500m of capital spending was shifted to cover day to day running costs. But despite transferring money from capital to resource, half of NHS trusts (hospitals, mental health and community providers) ended the year in deficit and were reliant on a range of one-off temporary measures to manage their finances. In 2017-18, the overall deficit across all 242 NHS trusts was £960m and this pressure continues. NHS Providers estimate that stabilising NHS Trusts’ finances might require up to £1.8bn of extra funding.

Restoring waiting times to the performance standards set out in the NHS Constitution would add a further cost pressure. The Health Foundation and IFS estimate that treating all A&E patients within four hours and meeting the 18 weeks target for planned care would add £2bn to the cost of care in 2023/24.

Addressing the problems of NHS Trusts’ financial deficits and waiting times would require almost all the remaining funding growth over the next five years. As a result, there is less than £1bn of the additional £20.5bn of NHS funding for genuinely new improvements to quality or access.

What does this all mean for spending growth per person?

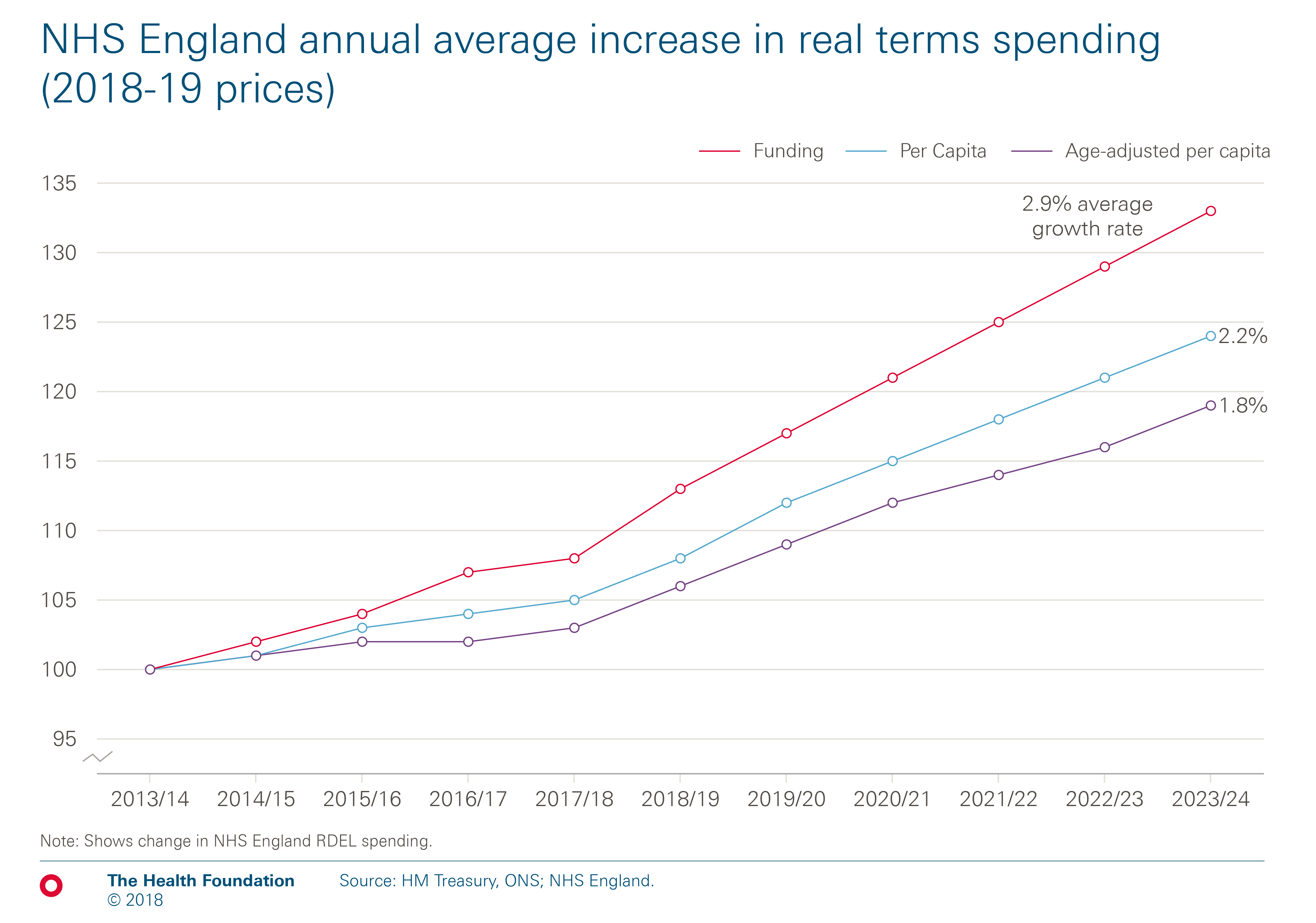

The annual average funding increase of 3.4% needs to be examined in the context of our growing and ageing population. The below chart compares the average growth in the overall NHS Budget over the next five years with growth in spending per person, and then adjusts for population ageing. NHS spending per person will grow by less than the budget increase; by an average of 2.8% a year. As the population is ageing, with one million more people aged 65 and over projected in the next five years, the increase in funding per person and adjusted for ageing falls further to an annual average of 2.3%. This is however, considerably more than the rate of increase for both of these measures over the last five years of austerity.

Tough choices?

The need to devote some of the new funding to stabilising NHS Trusts’ finances and improving waiting times is clear, but when added to rising demand and cost pressures it would account for almost all the additional funding announced by the Prime Minister, even with annual productivity growth of 1% a year.

This is clearly not the government’s ambition for the NHS over the next five years. The Prime Minister outlined a series of priorities in her speech for the NHS’s 70th anniversary. There were a mix of service improvements, including: waiting times; cancer and mental health; modernisation to improve efficiency; tackling the large variations across the system; and more use of technology. To make improvements in mental health alone to allow more people who need care to access help, would require an additional £3 billion in 2023/24.

To create some headroom to change and improve the NHS offer, something is going to have to give. The obvious area to look at is waiting times. There is a clear logic to reviewing the approach to waiting times so that some of the extra funding can be ‘freed up’ to invest in transformation or new areas of quality improvement.

If the NHS seeks to improve waiting times performance very quickly, the risk is that this will further add to cost pressures. The Health Foundation and the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimate that treating all A&E patients within four hours and meeting the 18 weeks target for planned care would add £2bn to the cost of care in 2023/24.

On-going workforce issues, particularly around nursing, raise real questions about the practicality of making quick progress on the 18 weeks target. Health Education England analysis shows that the NHS is unlikely to have enough staff for at least the rest of this decade based on current training plans and retention rates. Without enough permanent staff, the NHS would have to look to increase capacity through agency and temporary staffing which are more expensive.

But further to this, there are two key areas which need to be transformed if the additional funding is to be used optimally: the management of chronic conditions and productivity.

Transforming the management of chronic conditions

The health service’s capacity for and approach to providing ongoing care for people with long term health conditions, needs to change. Without change, the NHS will need considerably more hospital capacity. This will consume around £4bn of funding over the next five years. The Five Year Forward View sets out a strong case for a very different mix of capacity; promoting integration of services across organisational boundaries to deliver person centred outcomes. But the NHS now has 1,500 fewer GPs compared to two years ago, spending on community health services is falling and district nursing numbers have fallen by 40% over this decade.

More fundamentally, services for people with chronic conditions are fragmented. For example, almost all outpatients are managed on a specialty basis. Services make too little use of technology and too much care is focused on management of crises rather than proactive support to limit emergency exacerbations. Improving care in this way is not a silver bullet and there is little evidence that it would actively reduce cost, but it may improve outcomes for patients and improve the efficiency of care. It is almost impossible to imagine how some increase in hospital activity can be avoided. But it would be a missed opportunity to spend all the extra money on maintaining the current model of care rather than transforming it to improve outcomes and value for money.

Improving productivity and reducing waste

The second area of transformation relates to the need to deliver sustained improvements in productivity by reducing the unwarranted variations in care that Theresa May highlighted, so that good practice is spread consistently throughout the NHS. The five year funding settlement needs the NHS to continue to improve productivity. Over the last 20 years, NHS productivity in England has increased by around 1% a year. Continuing productivity growth at that rate is the minimum needed if the additional funding is to allow the NHS to maintain quality and access to care.

Reducing unwarranted variation is something the health care system struggles to achieve. Within NHS Trusts there is scope to further improve productivity but it will need investment in equipment and technology, but most critically, in supporting clinical staff to work differently. The benefits of new technology won’t be fully realised unless teams are provided with the implementation support to successfully embed it in their own pathways and redesign their work accordingly. The challenge is also seen in spreading new ideas to improve care from one area to another, as it often needs substantial time, resources and creativity to translate an idea into a new setting and make it work.

The government makes a substantial investment in initial training for people to qualify as a doctor, nurse or allied health professional. Investment in developing staff post-qualification is much lower and has been cut over recent years. NHS staff need time to develop new ways of working for patients to flow through the system as seamlessly as possible and clinical variations identified by the Getting it Right First Time (GIRFT) and RightCare programmes to be addressed. For clinicians to be able to work effectively together, there must be investment in the skills and capacity of teams rather than just individuals.

Research has explored successful change in the NHS and beyond. Access to appropriate data is important, for example through audits, as are people with the expertise to analyse such data for those designing and delivering care. But the quality and capacity of management also matters. Management is too often seen as a bureaucratic overhead, but without high quality management the NHS is unlikely to realise the productivity and quality gains it needs.

Day to day pressures on the NHS will always trump investment in the long term. A report by the Health Foundation and the King's Fund examined the case for a dedicated transformation fund following the launch of the NHS Five Year Forward View. Drawing on lessons from previous change programmes in health and other sectors it found that transformative change required investment, took time, and recommended the creation of a transformation fund. As the NHS develops the new long term plan, there is a strong case for a hard ring fence around a pot of dedicated funding for transformative change in hospitals and wider health services. Setting aside these extra funds would give us a system better prepared for the demands of the future.

The final pieces of the jigsaw

The additional funding announced for the 70th anniversary of the NHS was restricted to the NHS England budget. It excluded the wider Department of Health and Social Care budget (DHSC), which includes money to train new doctors and nurses and capital investment in buildings and equipment. Most importantly it didn’t cover the ring-fenced pot for health prevention, which has been cut over recent years. As a result, we now spend 30% less on smoking cessation services. And there is the big question of social care, which needs at least 4% a year and fundamental reform. A green paper is promised for this Autumn. Without necessary funding uplifts for the wider DHSC budget and a credible plan for social care it will be hard to spend that NHS cash well.

Anita Charlesworth (@AnitaCTHF) is the Director of Research and Economics at the Health Foundation

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more