Inequalities in life expectancy: how the UK compares

20 February 2024

Key points

- Substantial socioeconomic inequalities in health are well documented in the UK, but it is less clear how these levels of inequality compare across countries. Although complex to do well, international comparisons can be useful to guide policymaking on reducing health inequalities.

- Measuring socioeconomic inequalities in health across countries is not straightforward because of a lack of harmonised, timely data on health or mortality among different socioeconomic groups.

- To compare inequality in life expectancy in the UK to similar countries, we focused on two measures: life disparity (how much lifespan differs between individuals) and the gap between the lowest and highest mortality geographical areas (10th and 90th percentiles). We also calculated inequality in life expectancy between people with different educational levels.

- Our findings show higher than average variation in age at death and geographical area mortality in the UK than in other countries, raising concern about the extent of inequalities in the UK. We also found small-to-average educational inequality in life expectancy between people with low and high levels of education in the UK compared with other countries in 2010 and 2012.

- Overall, available data indicate that levels of inequality in life expectancy are higher in the UK than in other comparable countries, for example Italy and the Netherlands, but lower than in others, including the US and some Eastern European countries.

- Measuring inequality is an important first step in order to tackle unfair differences in life expectancy and health. Our analysis further highlights the need for action to reduce health inequalities in the UK, as well as countries we might learn from in some areas to accelerate progress.

Introduction

Life expectancy is widely used as an indicator of population health. Inequalities in how long people live are often described in terms of various socioeconomic factors (eg income, education), demographic characteristics (eg ethnicity, sex), geographical areas or inclusion health groups (eg people experiencing homelessness).

Although life expectancy is often compared across countries, less well known is how inequalities in life expectancy within the UK compare with those in other countries. Comparing the extent of inequalities between countries is complex, but it can be useful and may help policymakers to identify policies that could reduce inequalities in health.

We focus on two key concepts:

- Variation describes how far apart individual values are from each other and from the average (eg how spread out or dispersed values of age at death are in a country).

- Inequalities in health are systematic and avoidable differences between groups of people (eg variations in life expectancy between people with different levels of education).

This analysis compares the variations and inequalities in UK life expectancy with those in select European and high-income countries. We focus on life expectancy as a widely used indicator of population health and use measures suitable for monitoring inequality over time with open data.

Three ways of comparing variation and inequalities in life expectancy

Comparing socioeconomic inequality in life expectancy between countries is challenging. It requires studying socioeconomic groups that can be put into harmonised categories across countries. It also requires openly available life expectancy estimates from the same time period for each country being compared.

We compare variation and socioeconomic inequality in life expectancy using three measures that can be calculated with open data (Box 1).

1. Life disparity

We use life disparity (how much lifespan differs between individuals) as one measure of variation in age at death. The measure is easily calculable using openly available country-level data. From life tables, we calculated life disparity at ages 10 years and older for each one of 36 countries. A life disparity of 0 years indicates no variation in age at death, with everyone dying at the same age. A life disparity of 5 years means that the average years of life expectancy lost due to death is 5 years. Life disparity estimates are based on current mortality rates and may be poor predictors of future trends.

Although it is not a direct measure of inequality, countries with low levels of life disparity by definition have low inequality in life expectancy, while high life disparity reflects likely high inequality in life expectancy within a country.

2. Gaps in mortality between geographical areas

The second measure we use is variation in the average life expectancies of people living in different geographical areas within a country. This captures socioeconomic inequality better than simple variation across the whole population, since differences in life expectancy between places tend to reflect their characteristics (including available amenities and jobs) and populations (such as education and income levels).

We calculated the absolute and relative gaps in mortality between geographical areas with the highest and lowest mortality (10th and 90th percentile, respectively) in each country. We used population and death data from standardised areas (called NUTS3 (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) areas) in 31 European countries. For the most part, these areas have populations between 150,000 and 800,000 people, similar to Warwick and Leeds, respectively. However, some capital cities, including London, contain several NUTS3 areas; others are classified as a single NUTS3 area. Where a city is classified as a single NUTS3 area, variation within it may be masked.

3. Inequalities in life expectancy by education

Our third measure is the gap in average life expectancy between people with different levels of education. This directly measures systematic and potentially avoidable inequalities between socioeconomic groups. We used data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) on the absolute gap in life expectancy by education level in 25 European countries, separately for men and women. Education level was categorised using the International Standard Classification of Education 2011. Available data combine these levels into low (no school attended beyond Key Stage 3/Year 9), middle (completed upper secondary school or college, including vocational or technical training) and high (completed a university degree or equivalent). Few other direct measures are available for cross-country comparisons of socioeconomic inequalities. Gaps by area-level deprivation are often reported in the UK as a proxy for individual-level deprivation but cannot be used for international comparisons of inequality because few other countries calculate similar area-level deprivation measures. Average life expectancy according to income or ethnicity would be useful measures of inequality, but few countries report these.

Life disparity

- We used data from the Human Mortality Database, including demographic life tables by country and time period.

- Life disparity is a measure of variation in age at death, which reflects the total years lost due to death. It is calculated as a weighted average of the remaining life expectancy at age at death in a population.

- We used life disparity at ages 10 years and older to enable better comparisons between countries with different levels of infant and child mortality. Other measures of lifespan variation (including life disparity from age 0 years, standard deviation in age at death and Gini coefficient) all produced similar results to life disparity at ages 10 years and older.

- A key strength of these measures is that data are updated yearly and openly accessible upon registration.

- A limitation is that life expectancy calculations for each age group are based on current mortality rates and may therefore be poor predictors of future trends. In addition, this measure captures both systematic and avoidable differences in life expectancy – inequality – as well as random, unavoidable or non-systematic differences. Although not a direct measure of inequality, large variations in age at death suggest high inequality.

Gaps in mortality across small areas

- We used Eurostat data for each age group in NUTS3 areas in 31 European countries.

- NUTS regions were designed for the production of regional statistics and political interventions. They follow existing boundaries of administrative units in European Union member states. NUTS3 areas are equivalent to upper-tier local authorities in the UK.

- We calculated age-standardised mortality rates in each area using the European Standard Population to account for different population age structures across NUTS3 areas. Age-standardised mortality is closely related to life expectancy: areas with higher age-standardised mortality will have lower life expectancy, and vice versa.

- The measure has the advantage that data are updated yearly and openly available.

- A limitation is that the measure depends on area population size. Although NUTS3 regions should cover 150,000 to 800,000 people, outliers exist, such as capital cities. For example, London is broken up into individual local authorities, while other European capitals are classified as single areas. This may mask variation within European capitals and make variation in the UK look more extreme (see NUTS guidelines). To help address this, we grouped inner-London local authorities together to improve comparability with other European capitals.

Inequality in life expectancy by education

- We used data from the OECD on the absolute gaps in life expectancy by education level in 25 European countries. We looked at men and women separately.

- We present data on the absolute gap in life expectancy between the highest and lowest educational levels at age 25 years, by which age most people have completed their education.

- This approach does not take into account the proportion of the population at each education level. Where the proportion of the population at an education level is very small, it indicates a more marginal group, possibly with more extreme mortality compared with a larger group with the same level of education in another country.

- The key strength of these measures is that they directly capture the magnitude of inequality in length of life across socioeconomic groups. Further, data from OECD analyses are openly available.

Limitations include differences in how the data are captured between countries and infrequently updated data. In some countries, education level is recorded on death certificates; in others, linkage to another source (eg census) may be required, or such information may only be available for a subset of the population, introducing possible sources of bias. Further, comparable country data are updated infrequently. For example, 2011 data are the most recently available for the UK.

Comparing life expectancy and life disparity between countries

Figure 1 shows life expectancy and life disparity for selected European and high-income countries between 2015 and 2019. Japan and Hong Kong have the longest life expectancies at birth (almost 85 years), while the US performs relatively poorly among wealthy countries, with a life expectancy of 79 years. Life expectancy in the UK is 81 years.

Countries in the bottom right of the figure on slide 2 have higher life expectancies and lower disparities, while those in the top left of the graph have lower life expectancies and higher disparities. Life disparity tends to decrease as life expectancy increases. This is because countries tend to achieve increased life expectancy by avoiding preventable deaths in young adulthood or middle age. As deaths are pushed closer to the age of life expectancy at birth (now around 80 years in many countries), the variation in age at death – and therefore life disparity – reduces.

Figure 1

With a life expectancy at birth of 81 years, the UK’s life disparity between 2015 and 2019 was 10.04 years, similar to Germany’s. The UK’s life disparity is greater than most countries with a similar life expectancy at birth, including Ireland (9.5 years) and the Netherlands (9.4 years), although lower than France (10.3 years for a life expectancy of 82.5 years at birth) and Canada between 2015 and 2019.

Looking at historical trends can help us to put into perspective different countries’ current levels of life disparity. The contexts in these countries has changed considerably over time as a result of social change, technological advances, wars and economic shocks. Explore some of the trends between 1945 and 1949 and 2015 and 2019 in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2

Figures 1 and 2 suggest that the UK had greater variation in life expectancy between 2015 and 2019 than other European countries such as Italy or the Netherlands, but lower levels of variation than France or the US.

Mortality by age at death

Patterns of age-specific mortality rates can help us understand the drivers of life disparity. The US’s very high life disparity is due to substantially higher mortality in childhood and young adulthood relative to most other western European countries (Figure 3). Deaths at younger ages – those furthest from the mean age at death – have a larger effect on life disparity. Italy has lower mortality in young adulthood and middle age than the UK and France, helping explain why its life disparity is comparatively lower. The higher life disparity in France compared with the UK may be due to slightly higher mortality rates in early childhood, young adulthood and middle age.

Figure 3

Variation in mortality across geographical areas

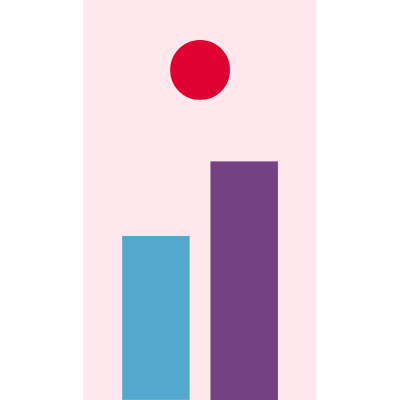

Figure 4 shows age-standardised mortality in the 10% of geographical areas with the lowest mortality (blue bars) and the 10% of areas with the highest mortality (purple bars) in each country. Countries in Figure 4 are ordered by the relative gap in mortality between the 10th and 90th percentiles, shown by the red dots. The absolute gap in mortality between the 10th and 90th percentiles is the difference in the height of the blue bar versus the purple bar for each country. Data are available for European countries only.

The mortality rate in the lowest (10th percentile) mortality areas in the UK is 841 deaths per 100,000 residents. This is relatively low compared to other countries. However, the mortality rate in the highest (90th percentile) mortality areas in the UK is 1,145 per 100,000 residents. This is higher than in several other western European countries. As a result, the absolute gap between the 10th and 90th percentiles in the UK is the seventh widest of the 31 countries with data on this measure. The relative gap in the UK – that is, the 90:10 ratio calculated as mortality in the 90th percentile divided by mortality in the 10th percentile – is the fourth widest of all countries studied (at 1.36). Only North Macedonia, Albania and Spain have higher relative gaps between areas.

Figure 4

These results indicate that the UK has larger geographical differences in mortality than other European countries. Several of the UK areas have small populations, which can result in larger differences between areas. However, we aimed to remove this effect by combining some UK areas in order to make them more comparable with other European cities.

Inequality in life expectancy by education level

The only measure of socioeconomic inequality in life expectancy available for comparison across countries was education level. The lack of regularly updated data is a key limitation of this direct measure of socioeconomic inequality in life expectancy. Some countries, including the UK, have not reported data since 2011.

The data from OECD countries in Figure 5 show the gap in life expectancy between the lowest and highest education levels, separately for men and women. Countries are sorted according to the size of this gap.

Figure 5 shows that, in most countries, education-level inequality in life expectancy tends to be higher – up to double – among men than among women. There are many possible explanations for this pattern, which our data did not allow us to test. These may include a higher prevalence of risk factors (for example, smoking, alcohol use and other risky behaviours) in men. In the UK, the education-level gap in life expectancy between the lowest and highest education-level groups was 4 years for both men and women.

Of the 25 OECD countries included in this analysis, the UK had the fourth smallest education-level inequality in life expectancy for men and was in the middle of the inequality distribution for women. Based on these data from 2009 to 2012, the UK had average or less inequality in life expectancy by educational level than most other European countries.

Figure 5

Implications for how we measure inequalities

The ability to easily compare levels of health inequality in the UK to those in other countries, at regular time intervals, is useful for guiding policy. Inequality continues to feature as an important concern of successive governments (including the last Labour government’s health inequalities strategy and the Conservatives’ more recent Levelling Up strategy), and the COVID-19 pandemic brought into focus the usefulness of cross-country comparisons.

However, our ability to make international comparisons is limited primarily to levels of health, with much less information available on how health outcomes are distributed within countries. Our analysis highlights several approaches that can be used to make international comparisons of inequalities in life expectancy (though not inequalities in other health indicators). It also highlights the need for action to reduce inequalities in the UK, as well as countries we might learn from in some areas to accelerate progress (such as Italy and the Netherlands).

Countries reporting on comparable measures of selected health outcomes at regular time intervals would be beneficial, and international organisations, such as the World Health Organization and OECD, could lead the development of metrics on within-country health inequalities through consensus with national bodies (such as the Office for National Statistics). Overall, making meaningful comparisons across countries requires a good understanding of their health systems and social and economic contexts, as well as awareness of the pitfalls in linking differences in policy to differences in health.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that variation in lifespan across the population is higher in the UK compared with many European and other wealthy countries. Life disparity in the UK is also relatively high compared with other countries with similar life expectancies, and variation across geographical areas is higher than in most other countries. Inequality in life expectancy by education level between 2010 and 2012 was low or average compared with other countries. However, we do not know how these inequalities by education level or other socioeconomic indicators have changed over the past decade in the UK relative to other countries.

Measuring inequality is an important first step to tackle unfair differences in who gets to lead a long and healthy life and who does not. Lower educational attainment and other forms of socioeconomic disadvantage are linked to shorter life expectancy. These socioeconomic inequalities reflect differences in access to the building blocks of health, including good-quality housing and jobs.

However, few up-to-date direct measures of socioeconomic inequality in life expectancy are available across countries. This presents significant limitations, restricting our understanding of how inequality in the UK compares with that in other countries. Life disparity and the 90:10 gap in life expectancy across geographical areas have weaknesses and are not direct measures of health inequalities arising from socioeconomic factors. However, in the absence of standardised socioeconomic data, these measures are useful because they can be compared across countries, allowing for more timely monitoring of how the UK is performing. Quantifying variation in life expectancy across countries points to where changes can be made to improve health equity.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more