Retaining NHS nurses: what do trends in staff turnover tell us?

3 April 2023

Key points

- Nurse shortages are a key contributor to NHS workforce shortages. Registered nurse posts consistently account for more than a third of all full-time equivalent vacancies in NHS trusts in England.

- Understanding how the NHS competes for nurses is crucial for better workforce planning and pay determination. In this analysis we examine the movement of employees into and out of the NHS nurse labour market in England between 2011/12 and 2021/22.

- During the decade to 2021/22, the majority of those who left NHS registered nursing (but stayed in work) took up other jobs within health and social care. Nearly 2 in 5 (38%) moved on to nursing jobs outside of the NHS and adult social care, including in private hospitals, agencies and charities, with a further 5% moving to adult social care nurse roles. Other common moves were to alternative health and care occupations, such as nursing auxiliaries and assistants (11%) and midwives (10%), most of which were within the NHS.

- While the proportion of moves to the independent and other sectors was largely unchanged over the decade to 2021/22, the NHS risks losing more nurses to the independent sector if the absolute number of NHS nurse leavers increases. The latest NHS Digital data point to higher NHS nurse leaver rates in the 2 years to September 2022, which underlines this risk. This could exacerbate NHS staffing shortages and hinder the NHS’s ability to increase activity rates and address backlogs.

- The data also show that many NHS nurses were previously employed as health care assistants, adult social care workers and home carers. Policies that aim to address staff shortages only in the NHS could therefore exacerbate vacancies in social care.

- Our findings underscore the need for a comprehensive long-term workforce strategy that accounts for how the NHS nurse labour market interacts with non-NHS nurse labour market and the wider economy.

NHS nurse shortages

Workforce shortages are one of the biggest challenges facing the NHS and adult social care in England. In the quarter to December 2022, vacancies in NHS trusts stood at around 124,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff, which is well above pre-pandemic levels. Nursing remains a key area of shortfall: in NHS trusts, while registered nurses and health visitors make up around a quarter (26%) of FTE roles, nurse vacancies accounted for more than a third (35%, around 43,600 FTE) of all vacancies in the quarter to December 2022. While seriously understaffed, the NHS continues to grapple with spiralling elective care waiting lists and ongoing industrial action.

In this context, there is mounting concern about whether the NHS can motivate and retain staff it desperately needs, particularly nurses. Overall, the staff leaver rate in NHS trusts has been on the increase in the last two years, from 9.6% in the year to September 2020 to 12.5% in the year to September 2022.

In the same period, the leaver rate for NHS nurses and health visitors also increased from 9% to 11.5%. This runs counter to the NHS Long Term Plan’s stated (albeit pre-pandemic) ambition to bring the nursing vacancy rate down to 5% by 2028. The absolute number of NHS nurse and health visitor leavers also increased sharply from just under 30,000 to nearly 40,900 in this period, the highest level on record (NHS Digital trend data begin in the year to September 2010).

About our analysis of staff turnover trends

Here, we take a step back and explore trends in staff turnover among NHS nurses during the decade from 2011/12 to 2021/22. We identify source occupations (where NHS nurses were employed before starting their NHS nursing roles), and destination occupations (where NHS nurses moved after leaving their roles).

We focus on NHS nurses for three reasons. First, because nurses account for more than a third of all FTE vacancies in NHS trusts. Second, while the NHS employs more than 3 in every 4 working nurses (78%) in the UK, the extent to which the NHS competes for nurses with the wider nurse labour market, and how flows between the two compare to nurses moving into other occupational groups, remains poorly understood. And third, our previous work points to nursing having been a major destination occupation for lower paid adult social care workers who changed occupations during the decade to 2021/22.

A better understanding of how the nurse labour market operates is crucial for resolving longstanding NHS staffing shortages. Left unaddressed, these shortages are likely to worsen and severely impede efforts to tackle the elective backlog and delays in hospital discharge.

Where do NHS nurses come from and move to?

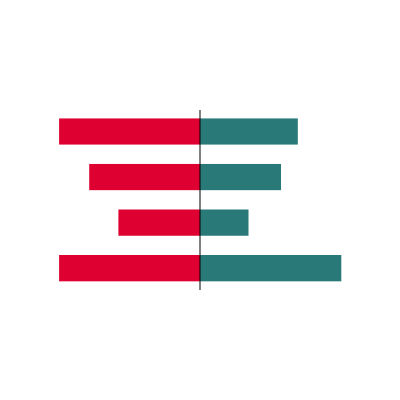

Figure 1 shows the leading source occupations (where people worked before) and destination occupations (where they worked afterwards) for NHS nurses, excluding NHS nurse jobs and moves into self-employment, retirement and inactivity, as the data do not enable us to explore these.

Figure 1

The red bars on the left of Figure 1 show the distribution of source occupations. The largest single source occupation for NHS nurses is nursing auxiliaries and assistants, accounting for around 1 in 5 (20%) entrants who were previously recorded as being employed, followed by care workers and home carers (10%). The eight leading source occupations for NHS nurses include other areas of nursing, such as adult social care nurses (4%) and independent and other sector nurses (10%). It is notable that NHS nurse roles attract employees from a very wide range of occupations: while the eight leading source occupations account for around 3 in 5 entrants (60%), the remaining 40% cover as many as 184 different occupations.

The green bars on the right of Figure 1 show the key destination occupations for NHS nurses. Jobs in the wider nurse and midwifery labour market are by far the most common destinations for those who leave NHS nurse jobs. Independent and ‘other’ nurse jobs (including nurse jobs in private hospitals, agencies, charities, and other destinations outside of the NHS and adult social care) account for nearly 2 in 5 (38%) of the total. The next three leading destination occupations are nursing auxiliaries and assistants (11%), midwives (10%) – most staff in these two groups remain in the NHS – and adult social care nurses (5%). Together, these four occupational groups account for close to two-thirds (63%) of destinations for NHS nurses in the 2011/12–2021/22 period.

To probe this further, we undertook our analysis separately for the first and second halves of the decade (2011/12–2015/16 and 2016/17–2021/22) and found no major difference in the proportion of NHS nurse leavers moving to the independent and other sectors in these two periods. Although this suggests that this proportion has not increased over time, others have shown that the absolute number of NHS nurse and health visitor leavers jumped significantly in the year to June 2022, to reach a 10-year high of around 40,400. NHS Digital data suggest that this number increased further to nearly 40,900 for the year to September 2022. That raises the concern that the absolute number of nurses leaving the NHS for roles in the independent and other sectors in 2022/23 may also have increased (even if the proportion were not to have changed significantly).

Non-NHS nurse and midwife jobs together account for more than half (53%) of destination occupations. A corollary is that relative to the source distribution, NHS nurses favour a limited set of alternative employment avenues if they seek to change occupations: the eight leading destination occupations in Figure 1 account for close to 3 in 4 destinations (73%) and the remaining 27% of destinations cover 145 different occupations. This is consistent with registered nurses having obtained formal qualifications, which allow them to access additional, and generally higher paying occupations, than most social care workers.

Implications for workforce planning

Our analysis provides new insights into nurse flows into and out of the NHS. We have two principal findings.

First, during the decade to 2021/22, the majority of NHS nurses who moved to roles outside of NHS nursing (but stayed in work) took up jobs in the wider nurse labour market. In many ways this is not surprising. Choosing to train as a nurse indicates an interest in a caring occupation. Nurses also invest significant time (and often money) to gain skills and qualifications. It is therefore to be expected that most choose jobs that use and reward those skills when they choose to leave NHS nurse jobs. The independent and other sectors were the most common destinations and accounted for nearly 2 in 5 (38%) of nurses who left NHS roles and remained in work in this period, highlighting that these sectors offer strong ‘outside options’ for NHS nurses. Our analysis suggests that this proportion was largely unchanged during this period, as opposed to varying substantially over the decade.

This has important policy implications, particularly if average nurse earnings increase more rapidly in the independent and other sectors relative to the NHS – such a scenario could see increased numbers of nurses leaving the NHS for roles in the wider nurse labour market. That would exacerbate NHS staffing shortages and hinder the NHS’s ability to increase activity rates and address backlogs.

In the context of high inflation, substantial gaps in average overall pay growth between the public and private sectors – as well as the ongoing NHS Agenda for Change staff pay dispute – have implications for NHS workforce planning. NHS nurse leaver rates already vary considerably across regions and provider types. As it can sometimes offer shorter or more flexible work hours (eg through shift work) than NHS trusts, the independent sector may be a more attractive alternative for NHS nurses in the current context, at least in some areas. If this results in higher numbers of nurses leaving the NHS for independent sector alternatives and those numbers vary across regions and provider types, NHS nurse shortages could be exacerbated and inequities in access to safe and high-quality NHS care could grow.

Second, our findings highlight that the two leading source occupations for NHS nurse roles during the decade to 2021/22 were nursing auxiliaries and assistants, a group that includes health care assistants, care workers and home carers. In line with our previous work, this emphasises that the NHS nurse labour market is closely linked to the adult social care labour market, with care worker and home carer roles potentially serving as a ‘stepping stone’ to working in NHS nursing. Policies seeking to improve NHS nurses’ pay and conditions should account for the inherent potential risk of exacerbating social care vacancy rates. Equally, policies that improve pay and conditions in social care may affect NHS recruitment.

Our analysis underlines that there is a strong case for improvement in data provision around NHS nurse turnover. The ASHE data that we use are classified as secure research data – there is a lack of publicly accessible data on this vital topic. From a broader perspective, our findings also highlight the need for a comprehensive long-term workforce strategy that accounts for how the NHS nurse labour market interacts with the non-NHS nurse labour market and with the wider economy.

Data citation and data appendix

Office for National Statistics. (2022). Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, 1997–2022: Secure Access. [data collection]. 21st edition. UK Data Service. SN: 6689, DOI: 10.5255/UKDA-SN-6689-20

For our analysis, we use data for 2011/12 to 2021/22 from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), undertaken by the Office for National Statistics. ASHE collects data on earnings from a sample of around 300,000 employee jobs (1% of the population) every year. We use the 2007 Standard Industrial Classification (SIC 2007) to define the health and adult social care sectors. We use the 2010 Standard Occupational Classification (SOC 2010) and a public–private sector identifier in ASHE to distinguish between nurses working in the NHS, the independent health care sector, adult social care and elsewhere (‘other’ nurse roles).

Importantly, we are able to distinguish reasonably well between NHS nurses and nurses employed in the independent health care sector, in adult social care and elsewhere (eg in charities), although there may be a few overlaps (eg it is unclear whether nurses working in general practice are consistently classified as being NHS nurses or independent sector nurses). In a small number of cases where individual nurses have multiple jobs, we record only the ‘main’ job (accounting for the most work hours) for clarity and consistency.

The data come with caveats: first, the public–private sector identifier may not perfectly distinguish between NHS and non-NHS organisations (eg general practices may fit into both categories). Further, ASHE does not facilitate analysis of job moves within occupational groups (eg nurses who change jobs within the NHS) and moves from paid employment into self-employment, retirement or economic inactivity (eg maternity leave or career breaks). As this is better addressed by other datasets, we restrict our attention to NHS nurses observed to have moved to or from their occupational group at least once and remained in work during the decade to 2021/22.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more