From low quality homes to insecure tenancies: how housing harms health is changing

17 July 2019

Data from the English Housing Survey gives an insight into the standard and nature of the housing stock. Where we live matters for health: a good home will offer security, warmth and safety. A home that lacks these things can damage health: by being of poor quality, or by depriving people of stability or of income that could have been spent elsewhere.

The data also tell us something about how the changing nature of housing affects our health. It is decreasingly about poor quality homes, and increasingly about insecurity.

Housing quality has improved, but there are still too many non-decent homes

The most direct link between housing and health is when the actual physical condition of the house – whether because of damp or mould, the presence of hazards like faulty wiring, or because it is too cold – is harmful to health.

One way of measuring this is through the Decent Homes standard: a home is considered decent if it meets four criteria around minimum standards for health and safety, as well as reasonable standards of repair, modern facilities, and thermal comfort.

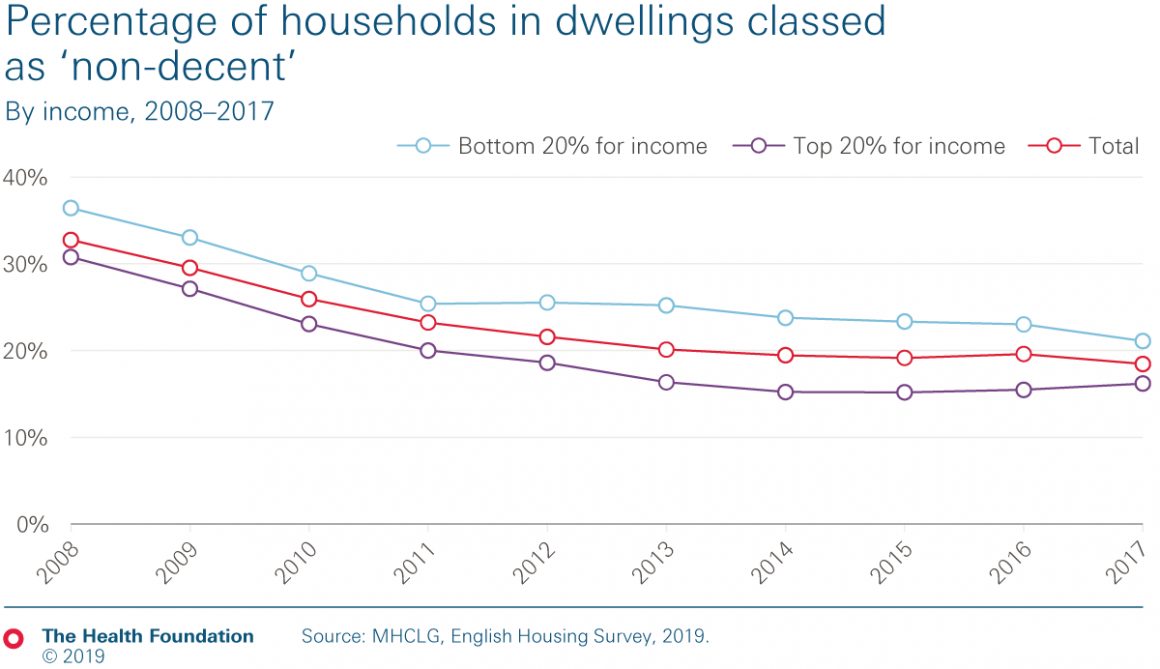

The proportion of households in England living in homes that fail any of these criteria has fallen since 2008, from around a third to 19% in 2017/18. This improvement in housing stock – on all dimensions of decency and for all housing tenures – is good news.

As always though, there are caveats. Nearly one in five households living in a non-decent home is still far too many, and this rises to one in four among private renters. As the chart above shows, those with the lowest incomes are more likely to live in a non-decent home: 21% of lowest income households live in non-decent homes, compared to 16% of highest income households.

The rate of progress in tackling non-decent homes has also slowed down in recent years. Between 2008 and 2012, there was an 11 percentage point reduction in the proportion of households in non-decent homes, compared to a 3 percentage point reduction between 2012 and 2017. This slowdown in progress should be of concern to policymakers.

Insecurity is becoming a more prominent challenge for health in housing

As well as the quality of the actual bricks and mortar of where we live, the security and stability of our housing matters for our health. Struggling to pay for accommodation, overcrowding and living under the threat of eviction all pose potential risks for health. These issues have been thrust into the spotlight by the growth of the private rented sector.

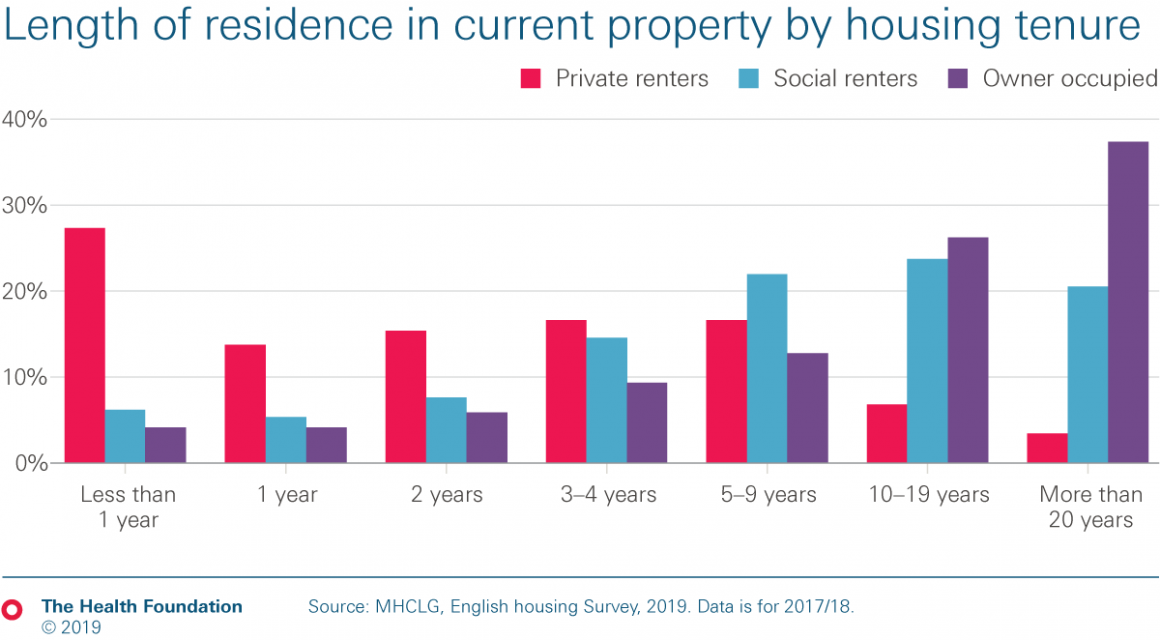

Exploring all these potential problems lies beyond the scope of this blog, but let’s look at the examples of insecurity and transience of accommodation. As shown in the chart below, a quarter of private renters have been in their current property for less than a year, compared to 8% of social renters and 4% of owner-occupiers.

This turnover wouldn’t necessarily be a problem, reflecting different accommodation needs at different stages in life, were it not for the fact that many of these moves are not voluntary. 11% of moves in the private rented sector in the last 3 years were due to notice from the landlord. A further 6% of moves stem from other problems with housing conditions, payment or problems with landlords. This can have serious consequences: from other statistics we know that the end of a shorthold tenancy is the main reason for home loss for 20% of households owed a prevention of relief duty by local authorities.

Compared to other tenures, the private rented sector tends to be more insecure and of poorer quality, and in return is more expensive (see, for example, research by the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence). The duration of tenancies and the quality of the stock have been improving, but the problem is that more people are renting privately – including families, where security might be more prized.

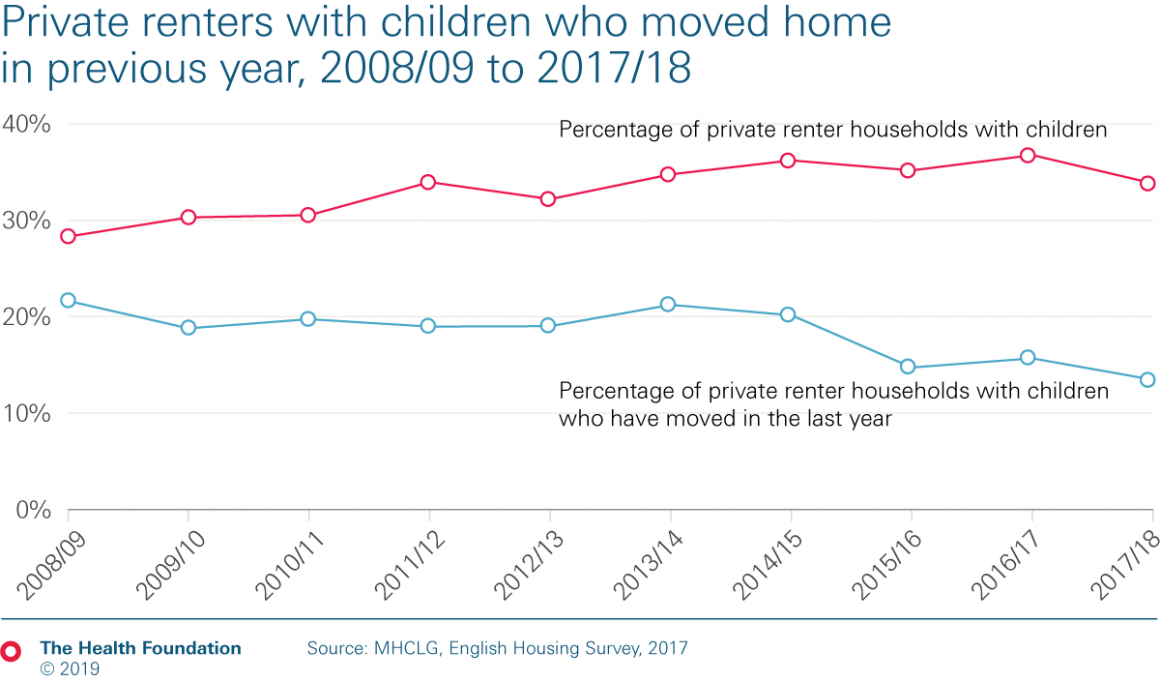

The chart below shows some of this: the proportion of families with children who have moved in the last year has fallen to around 13%. But families with children now make up a 34% of the private rented sector, although there has been a decline in the last year, it is too early to say whether this is a blip or the start of a new trend. So, more families with children – who may value stability for their children’s education and social participation – are in an insecure sector, even if it is improving.

The nature and quality of housing is an important determinant of our health. But the nature of the problems in housing are changing and pose different questions than 5 or 10 years ago. Policymakers are increasingly grappling with the growth in the private rented sector compared to the early 2000s, and what this means for insecurity. The outgoing government is moving to end no-fault evictions and legislated against agency fees. But more could be done: for example, Scottish tenancies are open-ended and have longer notices after a certain period of residence.

An ambitious agenda for housing needs to consider health, and this means thinking about quality and insecurity.

Adam Tinson (@AdamTinson) is a Senior Analyst in the Healthy Lives team at the Health Foundation

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more