Returning NHS waiting times to 18 weeks for routine treatment

The scale of the challenge pre-COVID-19

Returning NHS waiting times to 18 weeks for routine treatment

22 May 2020

Key points

- Reducing elective waiting times from ‘18 months to 18 weeks’ was one of the English NHS' major achievements in the 2000s. In January 2020, before coronavirus (COVID-19) began to impact on the UK, more than one in six patients were waiting more than 18 weeks for routine treatment. To free up NHS capacity, non-urgent planned care was postponed for 3 months from 15 April 2020.

- Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, to meet the 18-week standard for newly referred patients and clear the backlog of patients who will have already waited longer than 18 weeks, the NHS would have needed to treat an additional 500,000 patients a year for the next 4 years. The pandemic is likely to make waiting lists grow further and the challenge will be even greater.

- At the end of April, the NHS in England was asked to begin a cautious programme to resume some of the routine services suspended in response to COVID-19. Returning the NHS to ‘normal’ is hugely important but poses significant challenges. For example, treating patients with enhanced infection control arrangements will reduce the volume of patients that can be treated relative to normal.

- For planned hospital care, this challenge has to be seen against a backdrop of growing waiting lists and waiting times. In January 2020, before large numbers of COVID-19 hospitalisations, a total of 4.4 million patients were on the waiting list – around 730,000 of whom had waited more than 18 weeks.

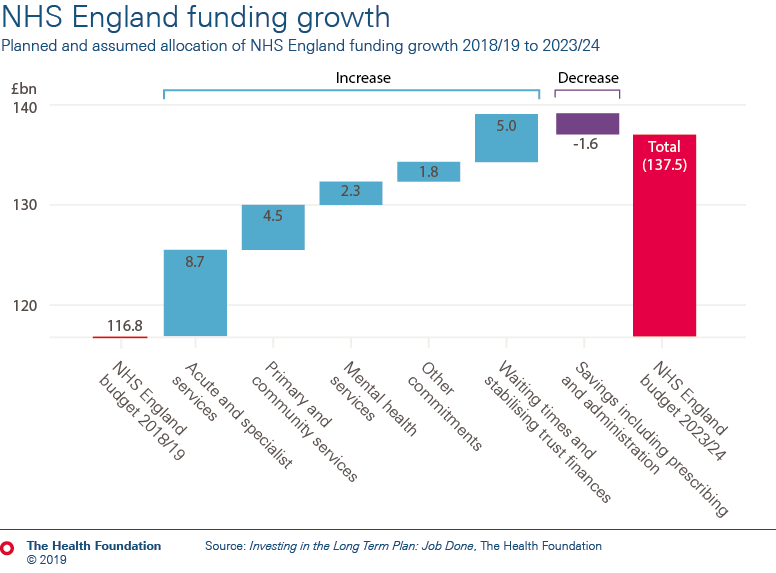

- The rates of spending growth, set out in the NHS Funding Bill in February 2020, will not be sufficient to cover the cost of meeting the 18-week standard by March 2024, even before any additional costs and demand arising from COVID-19. The Health Foundation estimates that spending growth would need to increase by a further £560m a year – assuming the NHS can prioritise patients to make the most effective use of available capacity.

- Without a radical intervention to increase capacity, it is unrealistic to expect the 18-week standard can be achieved by 2024 with current infrastructure and staffing levels. Meeting the 18-week standard would require hospitals to increase the number of patients they admit by an amount equivalent to 12% of all the patients admitted for planned care in 2017/18. This would be an unprecedented increase in activity.

- COVID-19 makes the challenge even greater. Over the coming years there will need to be long-term changes to how routine care is delivered, considerable effort at the front line and potentially an important role for the independent sector if the NHS is to return to a position of meeting the 18-week standard. But even with huge efforts, the reality is that longer waiting times for planned care are likely to be a feature of the NHS in England for several years at least.

Throughout the NHS’ history, providing timely care has been a major challenge for the health service. According to the OECD, in 2001 the median wait for a hip replacement in the UK was 215 days – more than double that of Australia (96 days).

For all the strengths of a taxpayer-funded NHS free at the point of use, long waits were often seen as the inevitable downside of the Beveridge model. Waiting times are routinely identified as an important factor in public satisfaction with the health service and patient experiences of NHS care. Long waits may mean patients experience additional pain, anxiety and inconvenience, and may lead to higher risk of harm and poorer outcomes.

In 2002, the Labour government committed to a major injection of NHS funding with one of the key aims being to dramatically reduce waiting times for NHS elective care in England. In 2004 this crystallised into the ambition to reduce waiting times from ‘18 months to 18 weeks’.

By December 2008, waiting times for elective care had fallen substantially: 90.3% of admitted patients and 96.8% of non-admitted patients were seen within 18 weeks. And international comparisons showed that the UK no longer had some of the longest waits – the median wait for a hip replacement in the UK fell from 215 days in 2001 to 78 by 2008.

But this transformation has not been sustained and waiting times are now making the headlines for all the wrong reasons. The standard that at least 92% of patients should wait no longer than 18 weeks to start elective treatment has not been achieved for nearly 4 years. This despite it being a legal right under the NHS constitution. And, in January 2020, before COVID-19 began to impact on the UK, more than one in six patients were waiting for more than 18 weeks.

Even without COVID-19, reversing the deterioration in performance against the standard would have required ruthless prioritisation alongside years of hard work, investment and reform. Before we factor in COVID-19’s impact, given the gap between current performance and the standard, what would it take for at least 92% of patients to begin treatment within 18 weeks, how much would it cost and is there a realistic prospect of delivery by 2024?

Figure 2 shows the percentage of patients on the waiting list for more than 18 weeks by specialty. All specialties but one (geriatric medicine) have missed the target since November 2018.

The NHS Long term plan (2019) promised extra funding to cut long waits for elective care and reduce waiting lists by 2023/24. Prior to COVID-19, planning guidance expected waiting lists to reduce in 2020/21. This may help to slow the deterioration in performance, but even before the pandemic recovering the 18-week standard looked very challenging.

It is important to note that these estimates may be low – they assume that waiting times have no impact on the rate at which GPs refer patients for specialist care or treatment thresholds in specialist care. If GPs responded to lower waiting times by referring more patients, for example, an even larger increase in NHS activity would be needed to meet the standard.

Table 1: Estimated cost of returning to the 18-week standard

| Base case scenario | High-cost scenario | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Annual | by end 2023/24 | Annual | by end 2023/24 | |

| Recurring | Extra activity over trend to stop waits growing | 210,000 | 210,000 | ||

| Cost per case for recurring activity | £1,800 | £2,800 | |||

| Cost of stopping waiting time pressures from growing (£m) | £378 | £1,512 | £588 | £2,352 | |

| Non-recurring | Backlog clearance to achieve 18 weeks | 1,300,000 | 1,600,000 | ||

| Cost per case for backlog clearance | £2,800 | £2,800 | |||

| Cost of backlog clearance (£bn) | £3,640 | £3,640 | £4,480 | £4,480 | |

| Total cost (£bn) | £5,200 | £6,800 | |||

Note: Health Foundation analysis of NHS Digital: Referral to Treatment (RTT): 18 Weeks RTT waiting times data following Findlay’s methods and NHS Digital Reference cost data.

In costing the additional activity needed to keep pace with demand, we calculate a weighted average cost of an inpatient treatment (£4,200) and an outpatient-based treatment (just over £500). This is based on the assumption that just over a third of the extra patients requiring treatment each year will need to be admitted to hospital. (For example, 36% of patients with incomplete pathways over 18 weeks required an inpatient admission in January 2020.) Our estimated cost is £1,800 per patient completing treatment.

For the backlog, following Findlay’s methodology, this analysis has increased the average cost by 50% on the basis that these cases will be more complex and, therefore, more costly to treat – leading to an average cost of £2,800 per patient.

These calculations are based on Health Foundation and IFS projection modelling, which estimates that £5bn would be needed to deliver NHS waiting times standards, including the 18-week standard, and return NHS providers to financial balance. Within this, the delivery of waiting time standards is estimated to cost around £2bn. This figure was based on Findlay’s initial estimates of the recurring pressures and backlog of 170,000 and 600,000 patients respectively.

If the backlog of patients waiting more than 18 weeks was evenly distributed across the 4 years (from the start of 2020/21 to the end of 2023/24), the NHS would then need to treat:

- 40,000 additional cases at an average cost of £1,800

- 175,000 ((1.3m – 600,000) / 4) cases per year at an average cost of £2,800

- giving a total of £560m more per year at an absolute minimum.

Our analysis suggests that the further lengthening of waiting times since publication of the NHS Long term plan means that the rates of spending growth, set out in the NHS Funding Bill in February 2020, will not be sufficient to cover the cost of meeting the 18-week standard by March 2024. This analysis estimates that spending growth needs to increase by a further £560m a year unless the extra investment planned for mental health, primary and community health services are scaled back.

General and acute bed occupancy in England was already at 92.0% – the maximum set by NHS England and Improvement – at the end of 2019 and nursing vacancies were over 40,000. Various measures in the NHS Long Term Plan should support more efficient delivery of some of the additional activity needed, but are unlikely to substantially reduce demand.

Even if the government is willing and able to increase NHS funding by £500m a year over the next 4 years, delivering the additional activity required to recover the 18-week standard is unlikely to be feasible. Around a third of people on the waiting list will need a spell in hospital. This would require hospitals to increase the number of patients they admit by an amount equivalent to 12% of all the patients admitted for planned care in 2017/18. This would be an unprecedented increase in activity.

So, even before the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, it was hard to see how the 18-week standard could have been achieved by the end of 2023/24 given the infrastructure and staffing levels. There is more that can and should be done to address the misery of long waits, and the NHS has already made commitments to do so. But until the health service has the capacity it needs to meet demand – and the support of a sustainable system of social care – a promise to recover 18-weeks within this parliament would be putting the cart before the horse.

Further reading

Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

View current vacanciesThe Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Find out more